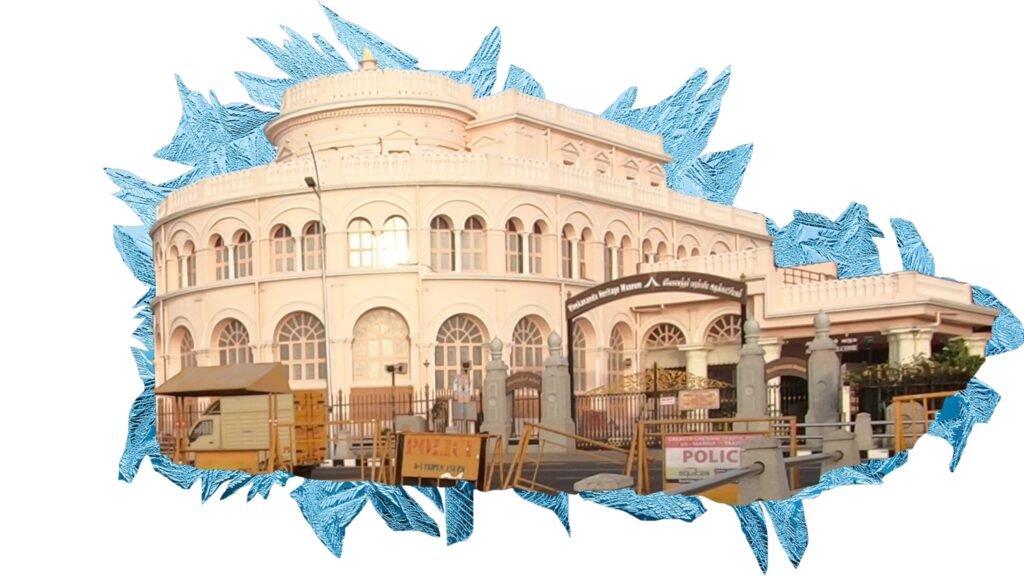

India is dotted with many old British buildings – some grand and iconic like the Gateway of India, and some odd and quirky like the current Vivekananda memorial in Chennai that was once a British Ice House!

These buildings tell us a lot about the period they belonged to. And on closer observation, you will spot a pattern that strongly corresponds to the changing status of the British in India. Their buildings were a reflection of the fears, ambitions and the practical concerns that the British faced at the time.

Many Indians see British colonial history as: “They came, they saw, they looted” (apologies to Julius Caesar). But when the British left, they left behind some remarkable institutions, and some beautiful monuments that are in use even today. This post explores the British approach towards monument-building, during their long stay (1612- 1947). To simplify things, let’s divide this period into three phases. The phasing is not watertight and is merely an arbitrary device for understanding a long continuum.

Detour: Watch this short video about one quirky British building that still stands, but in a very different form from when it was first built.

Phase 1 (1612-1749)

In 1612, the British East India Company managed to get a licence from the Mughal Emperor to trade in India. Then, they were only small businessmen trying to make a fast buck in a brand new market. They had no territorial ambitions. And they knew that they were no match for the mighty Mughals, anyway. Building monuments was really not on their agenda. All they built were wharfs and warehouses to handle their business. They also built some fortifications mostly to ward off other European rivals, and some churches for their own solace. And many of these were over-engineered into lasting monuments. For instance, the St. Mary’s Church in Chennai, built in 1680, is the oldest active Anglican Church in the Eastern hemisphere, and the Fort St. George built in 1640, still has a military garrison.

Phase 2 (1750- 1857)

By the 1750’s, the British had become a stronger power in India. Their European rivals here – the Portuguese, the Dutch and the French, had weakened considerably, and the Mughal Empire itself was crumbling. The British now owned a vast army of Indian soldiers and it was a tremendous psychological and practical advantage. They were no longer meek traders, but ambitious raiders. Following their territorial ambitions, they started investing in infrastructure. Their goods and armies had to be moved around, and the natives had to be impressed by their power. To make travel faster, the British introduced Railways in India.

Gigantic Town Halls and administrative buildings were built, broadcasting the ‘superiority’ of British rule from the roof-tops. During this phase, churches became more ornate. And they invested in unlikely luxuries like warehouses for storing blocks of ice all the way from America! At that time, British investments in India were, both emotionally and materially, large enough to merit huge monument building.

Phase 3 (1858-1947)

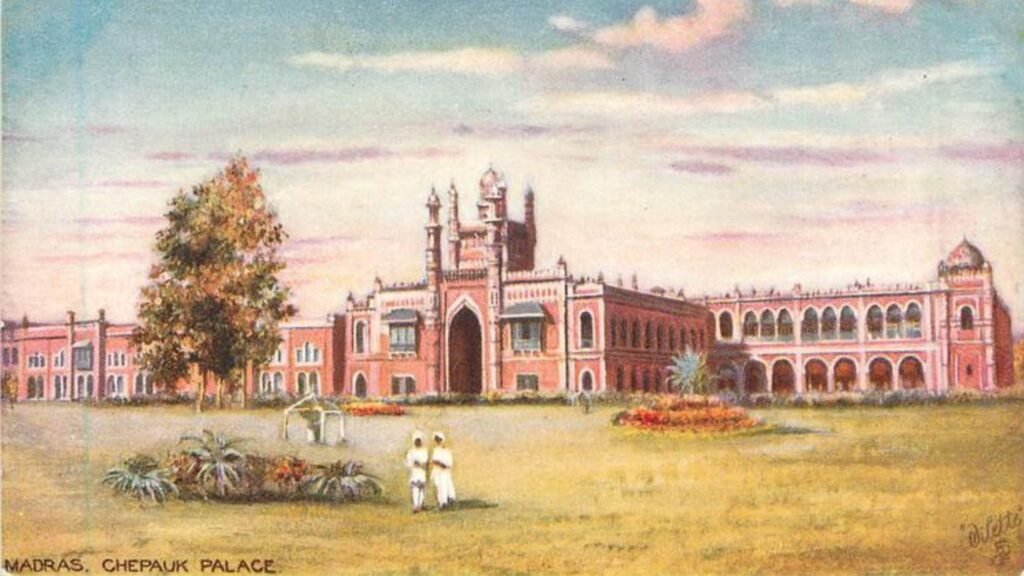

In 1857, the British ruthlessly crushed the Indian Mutiny and the very next year, Queen Victoria declared herself Empress of India. India became the British Empire’s most prized possession. British architects now unleashed their full creativity on India, designing beautiful universities, hospitals, railway stations, courts and museums. They had even evolved a new fusion architectural style called the Indo-Saracenic – a mixture of Hindu, Islamic and European styles of architecture. Guess who loved it, besides the British? The Indian kings! Most of the palaces constructed around that time are Indo Saracenic.

In the ‘old’ quarter of some Indian Colonial cities, you can still find British Monuments from all 3 phases. And there is no denying that these monuments enrich the place by their presence, and enthrall those who take the effort to uncover their stories.