In the early 1600s, Portugal, Holland and Britain, Europe’s superpowers at that time, were embroiled in a struggle to dominate India. Even while they were fighting it out, in 1620, Denmark quietly managed to establish a colony in Tharangambadi, a seaside town about 280 km from Chennai. They renamed it Tranquebar. And as the little colony prospered, the Danish king Frederick IV decided to introduce his Indian subjects to Christian values. But this was easier said than done. No Danish preacher was willing to travel all the way from Denmark to distant India.

Detour: Did you know that Christianity came to India almost 2,000 years ago?

Watch this short video for the story.

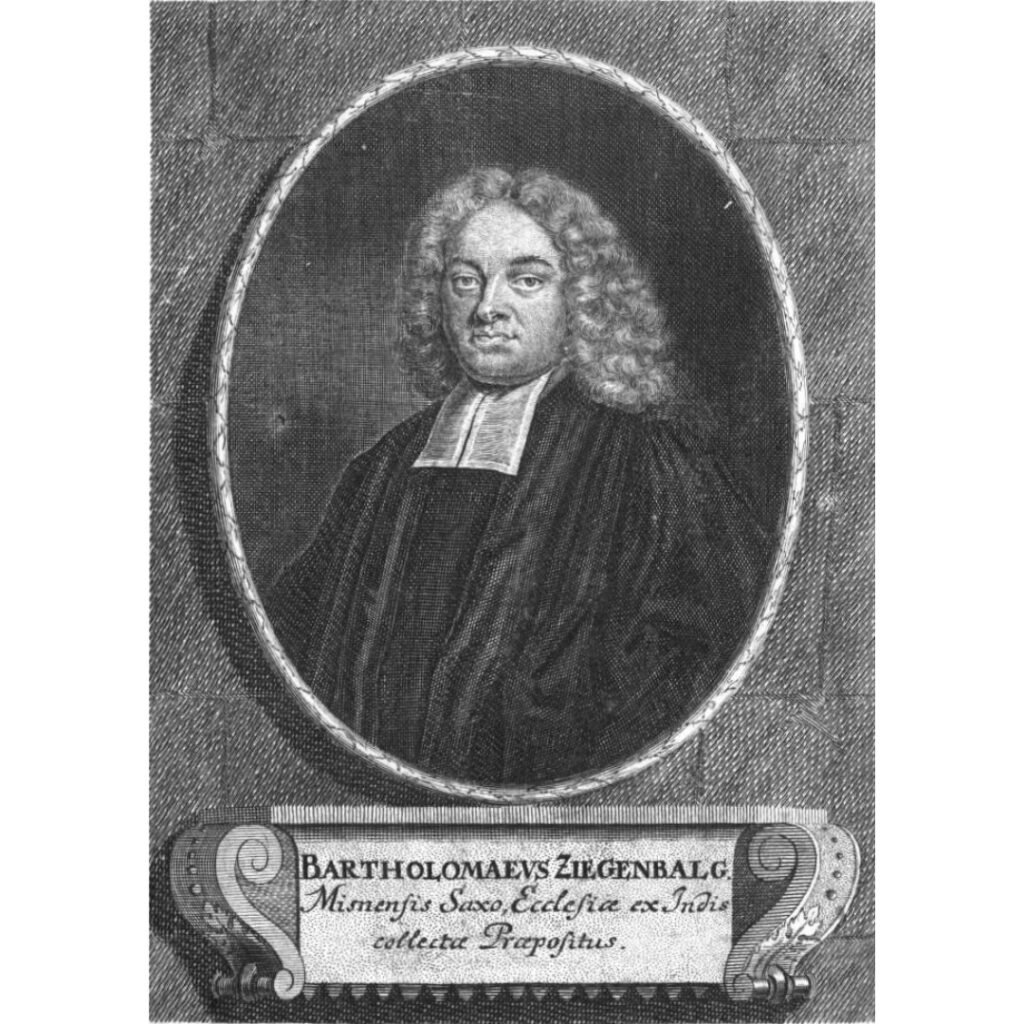

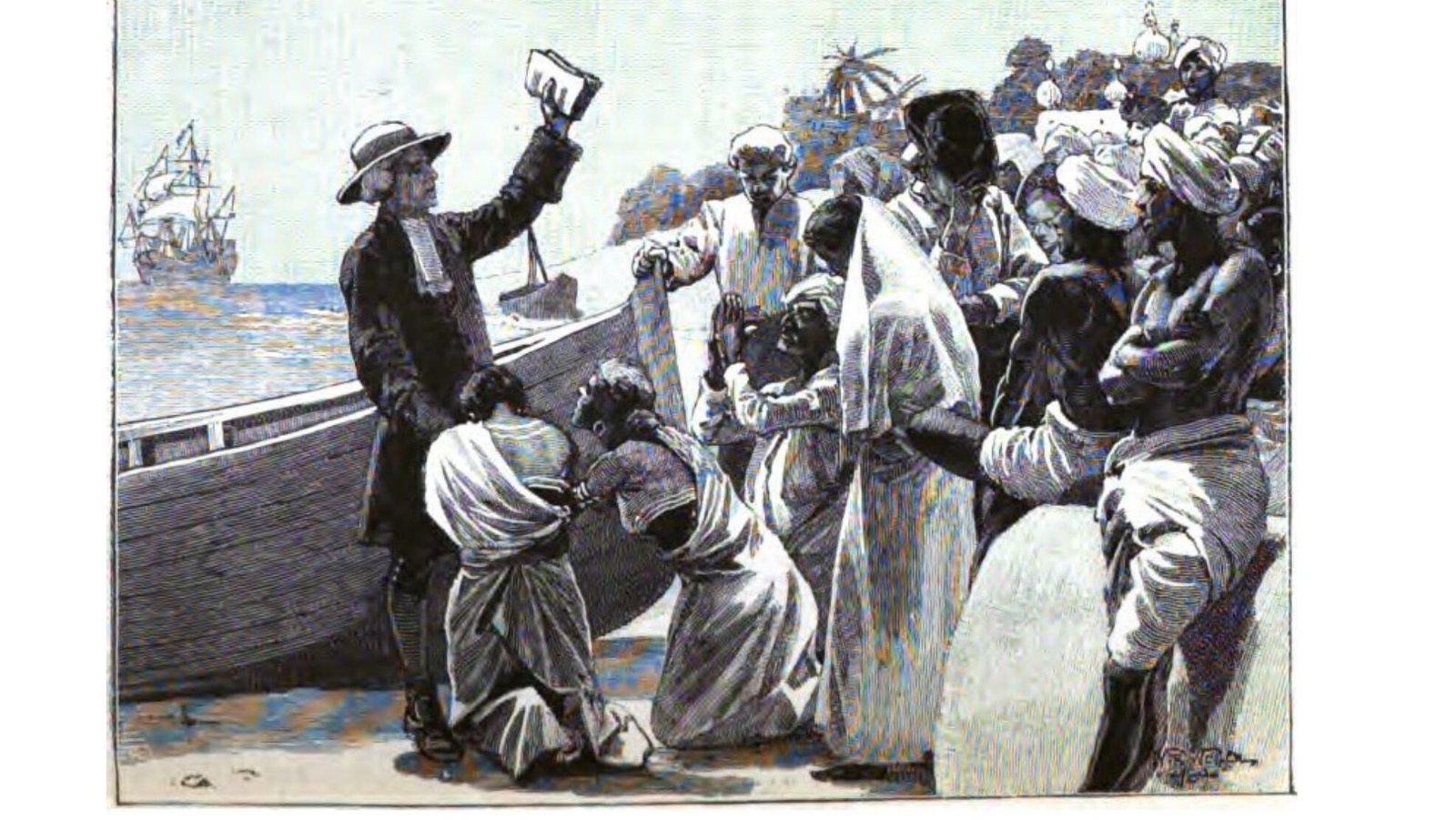

Just as the Danish Mission seemed set to fail, two German missionaries volunteered. One of them was a man called Bartholomaus Ziegenbalg. Even before Ziegenbalg set off, he realised he had a problem on his hands. How was a German going to preach to the locals who spoke neither Danish nor German? The only solution was to learn some Portuguese! Why Portuguese? In those days there was a Portuguese settlement in that part of India, and some of the locals were already familiar with Portuguese. But after he landed in Tranquebar, Ziegenbalg started developing an interest in the local language, Tamil. He decided to learn Tamil.

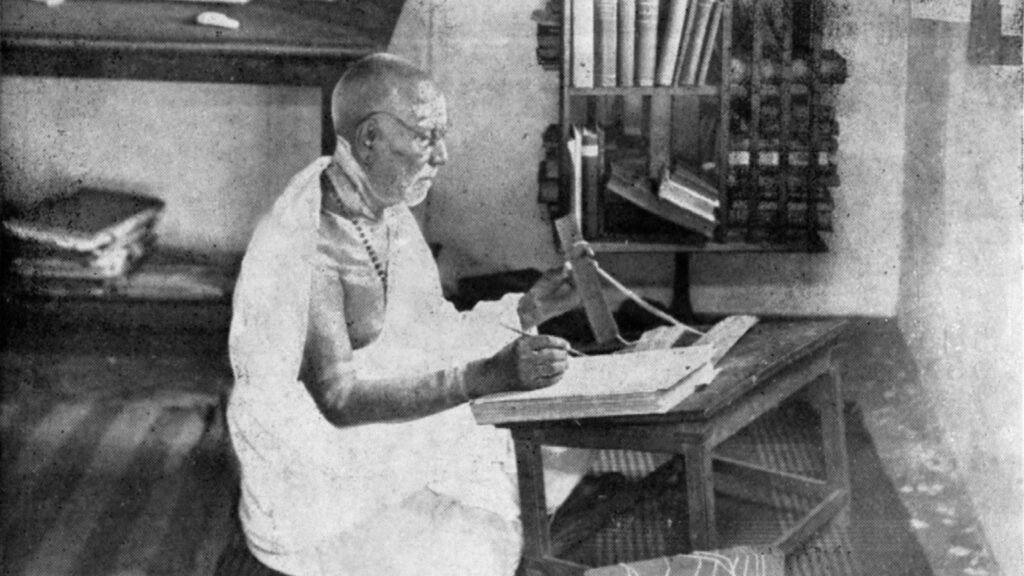

He invited a Tamil scholar to stay in his house and run a Thinnai-Pallikkoodam which literally means “school at the doorstep”. He sat along with the local children and learnt to write on the sand, Indian-style. He set himself a punishing academic routine – from 7 am to 8 pm. Even his lunch hour was not wasted: his assistant read out Tamil texts as he ate. So sincere was his effort that Ziegenbalg soon became an erudite Tamil scholar!

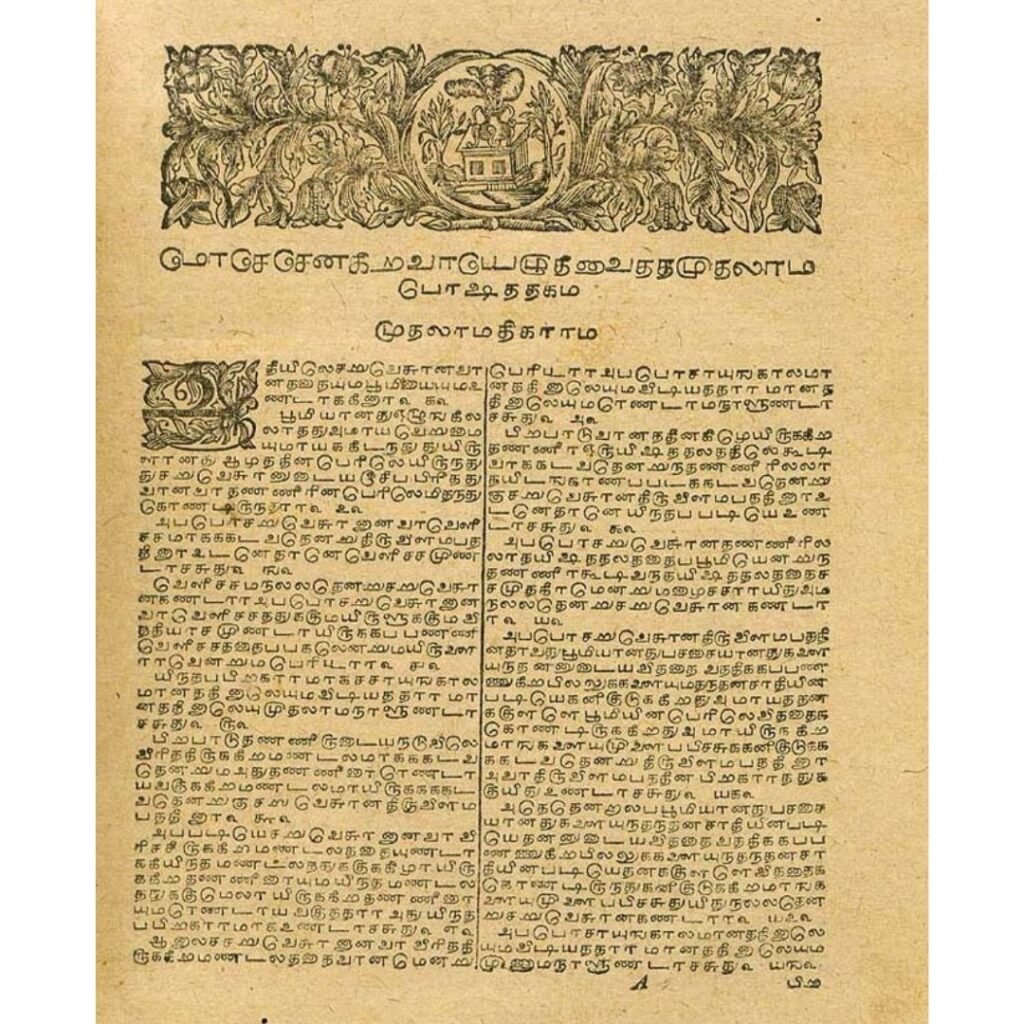

By 1708, he felt ready to translate the New Testament into Tamil. It took him three years to complete the task, and another three years to edit and revise it to his satisfaction.

But there was a problem. Ziegenbalg had no printing press for publishing the Bible. Luckily for him, help came from an unexpected quarter: the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London (SPCK). The British East India Company had consistently denied the SPCK’s requests to evangelise in India. The SPCK saw Ziegenbalg as a useful ally, and generously supplied him with the tools needed to print the Bible. And so, the first Tamil Bible was published in 1715. In fact, it was the first Bible to be printed in any Indian language!

But Ziegenbalg’s journey was far from easy. The Hindu orthodoxy viewed his preaching as cultural imperialism, and routinely opposed him. The resident Portuguese Catholic priest, Fernandez de Guevara, was jealous of his accomplishments and conspired to derail the project. While these were understandable reactions, surprisingly enough, the local Danish administration was unsupportive too. The Dutch Governor, Johann Sigismund Hassius, considered Ziegenbalg’s activities a distraction from commerce. Zeigenbalg didn’t help matters by rashly asserting that he was a royally appointed missionary. Their relationship soured and Hassius even put him in jail for four months under a flimsy pretext. Ziegenbalg, however, persisted with his efforts and finally succeeded in his mission. But all that stress took a toll on his health. In 1719, Ziegenbalg fell ill and died. He was barely 37 at that time.

Ziegenbalg was more than a mere Bible publisher. The New Jerusalem Church that he built in 1718 was the first Indian Lutheran church and the precursor of the Tamil Evangelical Lutheran Church. It has a rich tradition of Tamil liturgy even to this day. In 1707, he started a girls’ school, a pioneering step in women’s education. His greatest works were related to Indology — which covered Tamil grammar and literature, and Hindu scriptures. Sadly, many of these works received recognition only about two centuries after his death, because Europe of that time, was not yet ready to acknowledge that art and wisdom could originate from the East.

Ziegenbalg was laid to rest in his beloved New Jerusalem Church. In 2006, the Indian government released a postage stamp honouring Ziegenbalg on the 300th anniversary of the Tranquebar Mission.