The Greater Armenian Empire was in the middle of the ancient Silk Route. For centuries, Armenians travelled worldwide in pursuit of profits; so much so, even today, there are more Armenians outside Armenia (nearly 9 million) than within its borders (about 3 million)! Almost every major city has an Armenian Street: Boston, Beirut, Buenos Aires… and many more. In India, Kolkata has an Armenian street and Chennai has its own Armenian Street in George Town. Coincidentally, the Malaysian city Penang too has its Armenian street in its own George Town!

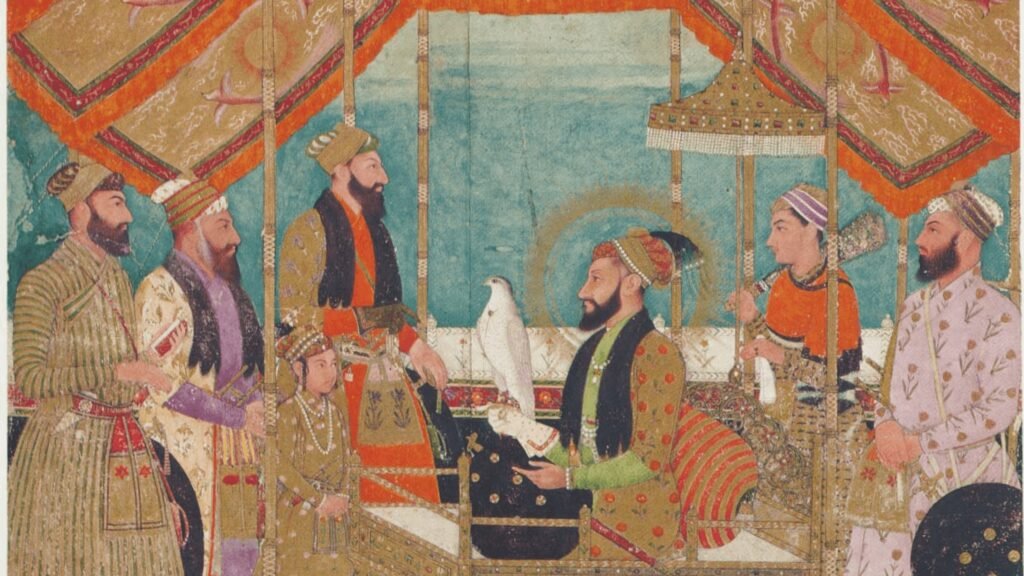

The Armenians probably started visiting India around the time of Alexander the Great (4th century BC); we know this from Cyropaedia, an ancient treatise written by Xenophon (430-355 BCE), a Greek commander and philosopher. When Emperor Akbar (16th century) encouraged them to invest long-term, the Armenians became inseparable from Indian history. Unlike other Indian minorities like Parsis and Jews, the early Armenian travellers were not refugees escaping persecution; they consciously came here for trade. At this time the Greater Armenian Empire extended from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea. The Armenian merchants built relationships with the aristocracy of every Indian society they encountered. Consequently, they did high-value trade and amassed huge wealth.

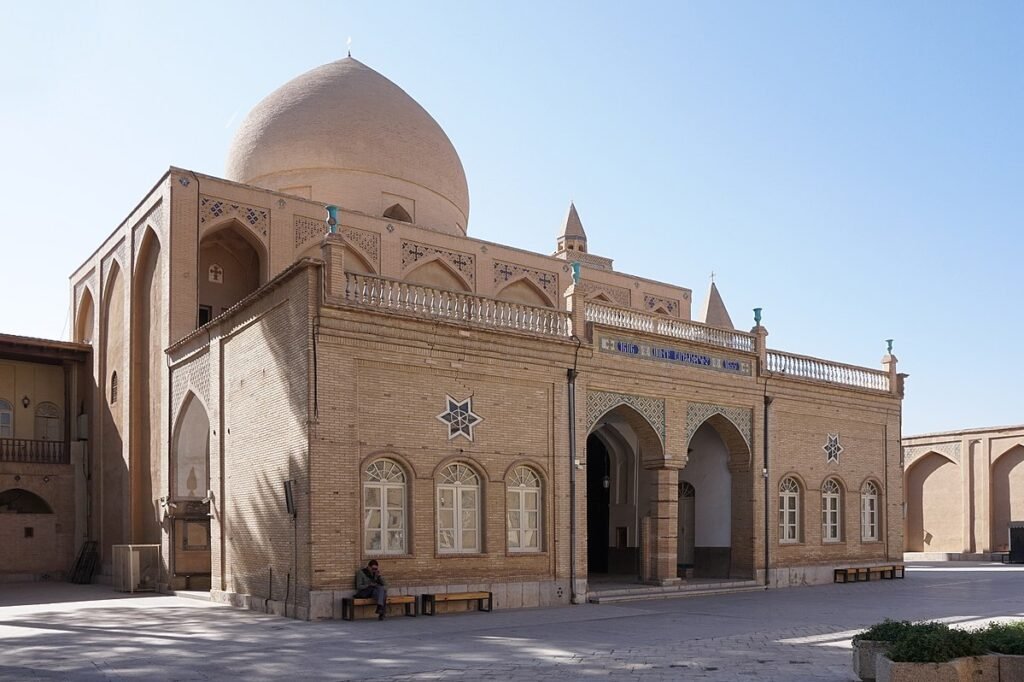

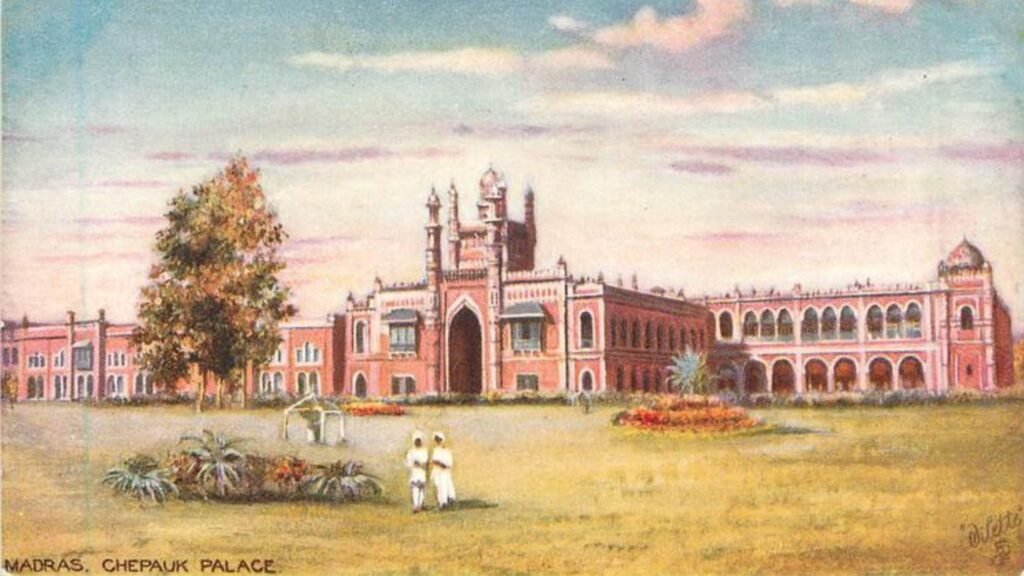

The Armenians started coming to Madras (now Chennai) around the 16th century. Most of them migrated from Julfa, a suburb of Isfahan in Persia. These Armenians had come to Isfahan because they were under threat from Turkey. When Turkey attacked Persia, they came to India. Over the years Madras became a growing commercial town with Portuguese, Dutch, Danish, British, French and Jewish communities investing in international trade. The Armenian business networks extended all over the world and they were leaders in the Indo-Spanish trade. So they easily succeeded in Madras. The British in India loved them because the Armenians improved the economy without threatening them politically – unlike the Portuguese, Dutch and French. Some Armenians even lived inside the British settlement at Fort St. George, like Coja Petrus Uscan, the famous Armenian patriarch.

Petrus arrived in India from the Philippines in 1723 and promptly endeared himself to the local Indian king, the Arcot Nawab. He also became a Councillor in the British East India Company. He was deputed by the British to negotiate a peaceful settlement with the Maratha general of the time when the latter threatened to attack Madras. Petrus succeeded in his mission with his outstanding diplomacy. He supported the Nawab of Arcot in diplomatic and financial matters and became very rich and influential in Madras. However, misfortune struck in 1746 when the French captured Madras. Petrus managed to escape to Tranquebar (Tharangambadi), the Danish colony, but the French seized a considerable portion of his business assets. The French Governor was intent on breaking British dominance in Indian trade, so he made a strange offer: if Petrus shifted his entire trade to the French colony of Pondicherry, he would get his assets back; otherwise, he could forget his assets forever.

A lesser man would have accepted the offer. Not Petrus! He would rather lose his wealth than betray his friends: after all, the British had encouraged his business. So he not only rejected the offer, but also cheekily advised the ambitious French Governor: confiscate my property if you must, but consider redistributing it among the poor; surely, the great French Government is not in desperate need of my assets? The British repossessed Madras in 1749 and Petrus was warmly welcomed back. What he lost in wealth, he gained in honour.

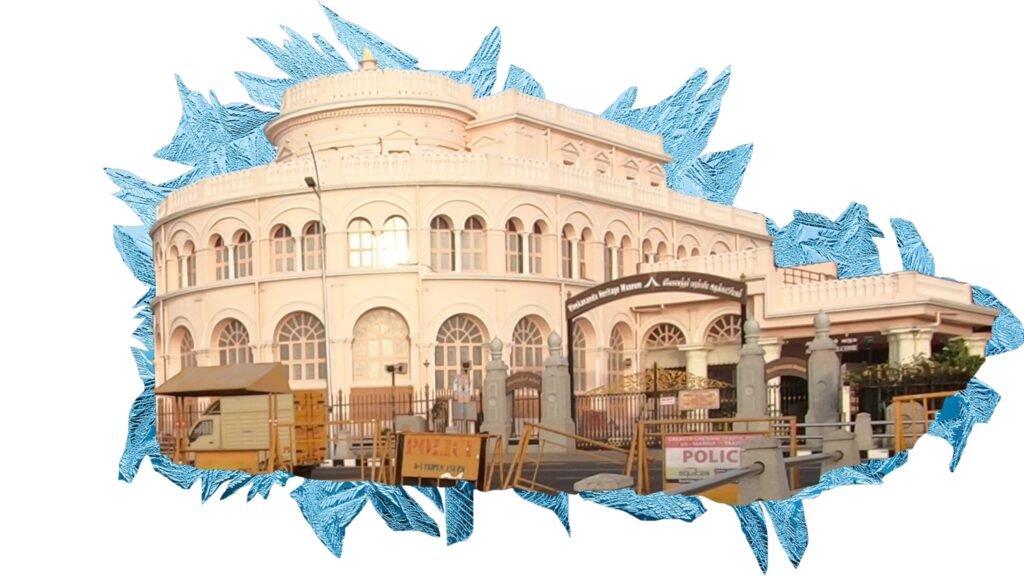

Loyalty was not his only virtue. Petrus donated wealth liberally. He contributed generously to the construction of St. Rita’s Church in Santhome. For the benefit of pilgrims to St. Thomas Mount, he constructed a step-way up the hillock; he built the first bridge across the Adyar river in Madras (the modern Maraimalai Bridge has since replaced it) so that devotees could ford the river easily. The bridge cost him Rs. 100,000 (a huge sum those days), and he topped it by providing Rs. 10,000 in trust for the annual maintenance of the chapel and the bridge. Deeply religious, Petrus worshipped at the Chapel of Our Lady of Miracles in Vipore (Vepery), which he owned privately.

When he died in 1751, he was buried in the same chapel. According to folklore, his heart was carved out and buried in his beloved birthplace – Julfa in Isfahan! This seems unlikely, though there is a portrait of Petrus in the Holy Savior’s Church in Julfa! Petrus had no children and his wife inherited his wealth (which was considerable despite the French expropriation). When she died, she left it all to charity. If you visit the serene Armenian Church of St. Mary at Armenian Street, you can see a plaque honouring the noble Armenian.