Karē raisu, or Curry Rice, is a widely popular dish in Japan. As its name suggests, it’s quite literally a flavourful curry poured over rice. But don’t you think this dish sounds like it has a possible connection to India? Well, that’s because the dish is native to India! But however did it make its way to Japan?

Here’s where the British, as usual, had a significant role to play.

By the 1850s, the British had established a stronghold in the Indian subcontinent and had started the process of expanding their dominion over other parts of Asia. It was during one such attempt that the British introduced the curry in Japan. You see, the British had grown to like the taste of Indian curry and they passed it on to their fellow officers – especially to those in Japan. However, their curry was prepared with curry powder, sour apples and flour, and wasn’t exactly rich in spice and flavour, like it was supposed to be, therefore losing all its “Indian-ness”. Japan adopted this recipe, which was a much sweeter and blander version of the authentic curry, and changed it over a period of time to suit their tastes. And thus was born the karē raisu, which became a staple food in Japan!

But one Indian revolutionary reclaimed the dish and brought its original flavour to the land of cherry blossoms. That man was Rash Behari Bose.

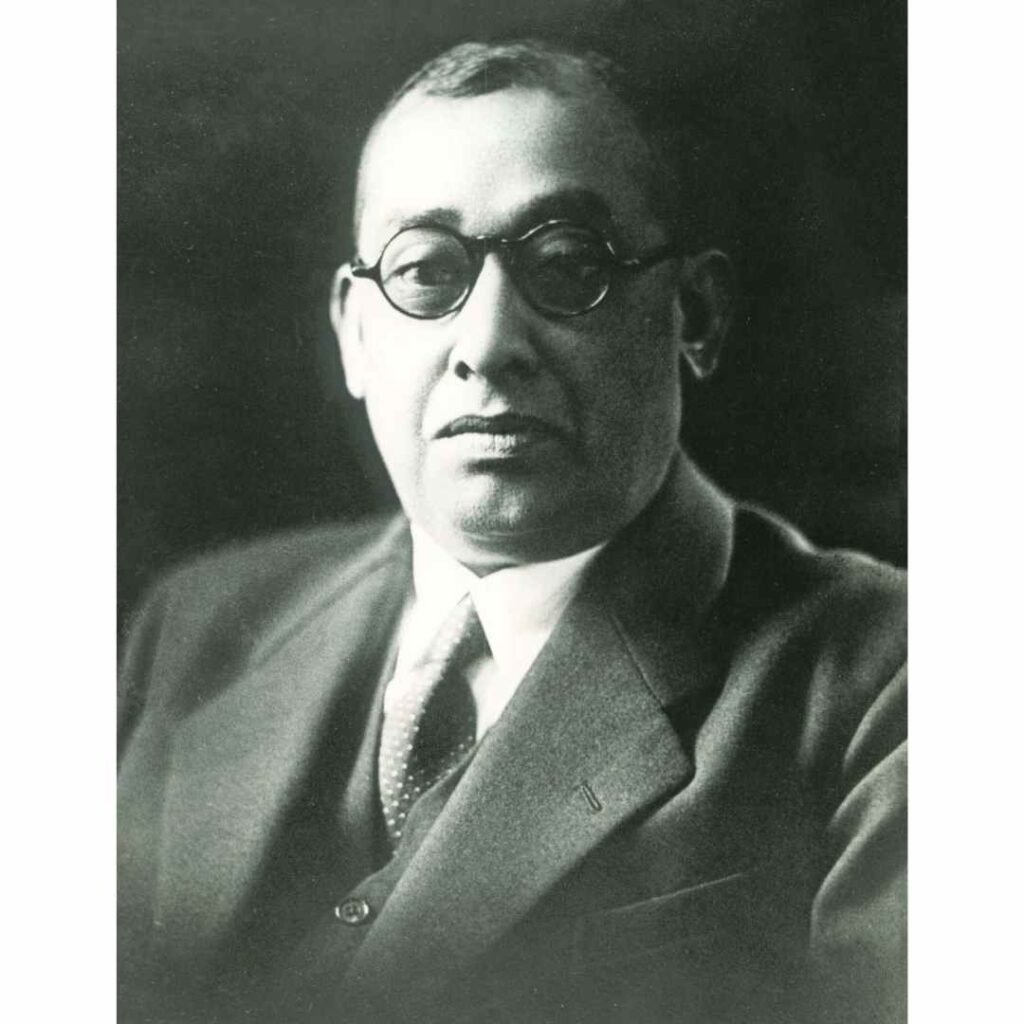

Who was Rash Behari Bose?

Born in the village of Subaldaha, West Bengal, Bose grew up with front-row seats to the deep inequalities of British India. From a young age, he was influenced by revolutionary ideas and harboured strong nationalistic feelings. After being denied entry into the army, he eventually began working as a clerk at the Forest Research Institute at Dehradun. However, his true dream was to work towards a free and independent India, and to pursue this dream, Bose joined a network of revolutionaries in Bengal.

In 1912, during the official ceremony of transferring the capital from Calcutta to Delhi, a group of revolutionaries hatched a plan to carry out the assassination of the then Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge. And the mastermind behind the plan? Bengal’s very own Rash Behari Bose. Although the assassination attempt was a failure, the British were determined to stamp out the revolutionaries once and for all.

However, despite multiple efforts, the British were unsuccessful in nabbing Bose, who had become quite the master of disguise. In fact, Bose is said to have returned to Dehradun after the attack and proceeded to lead a normal life. He even attended a public meeting and condemned the attack on Hardinge!

Three years later, Bose became an active participant in the Ghadar Movement. Initiated by expatriate Indians, the movement had its origins in the USA, and was aimed at inciting a mutiny against British rule in India. Sadly, the movement failed and alas, Bose was identified as a key conspirator against colonial rule. To avoid being arrested by the British, Bose fled to Japan.

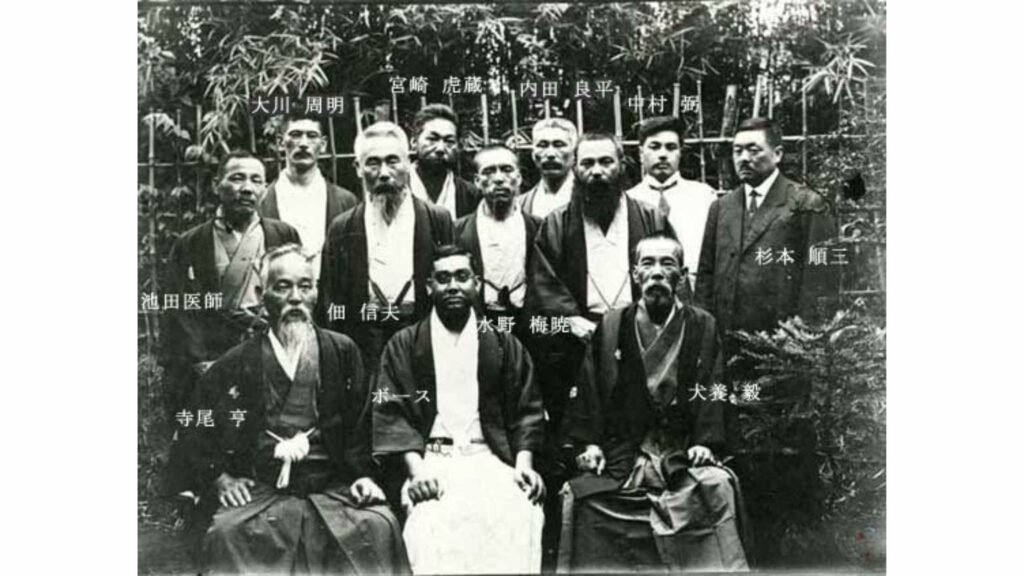

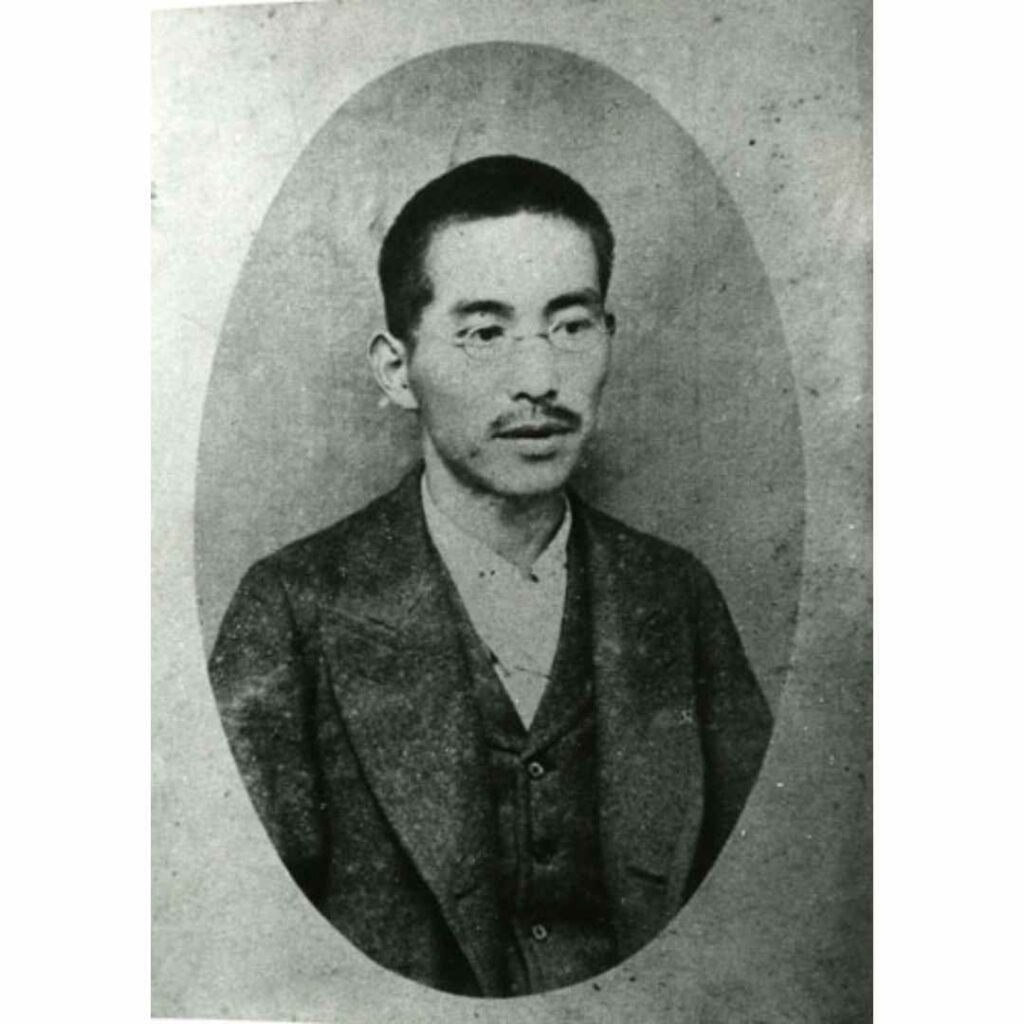

Mitsuru Toyama, a prominent Pan-Asian leader and Japanese politician at the time, was kind enough to offer Bose refuge in his house. But when the British ordered his extradition, the Indian revolutionary had to shift to a safer hide-out. He moved in with the wealthy Soma family, who were sympathetic to his cause.

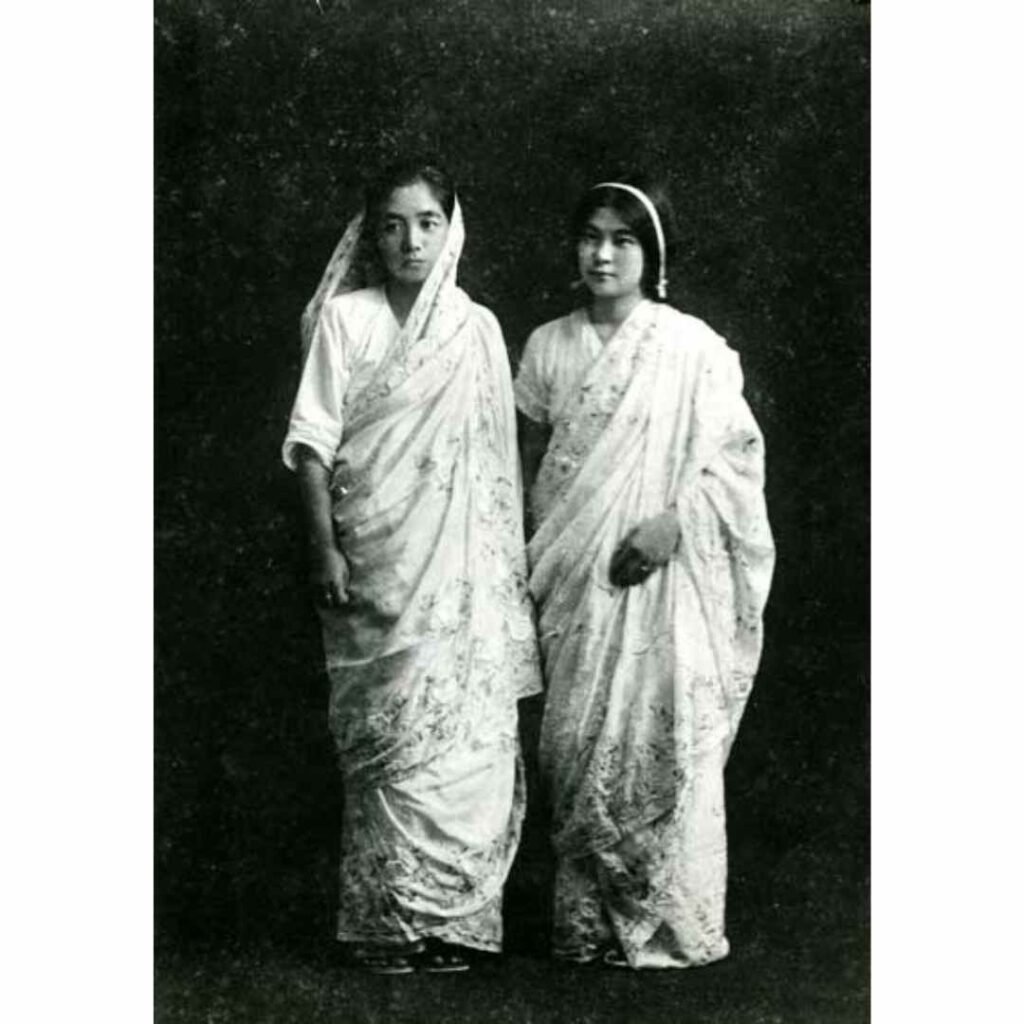

Little did Bose know that he would eventually come to call this family from the bustling district of Tokyo his own. Aizo and Kokko Soma, the heads of the family, sheltered him in their bakery, ‘Nakamuraya’, while Bose continued his revolutionary activities. He fell in love with Aizo and Kokko’s daughter, Toshiko, and married her in 1918. Thanks to their marriage, Bose also became a formal citizen of Japan.

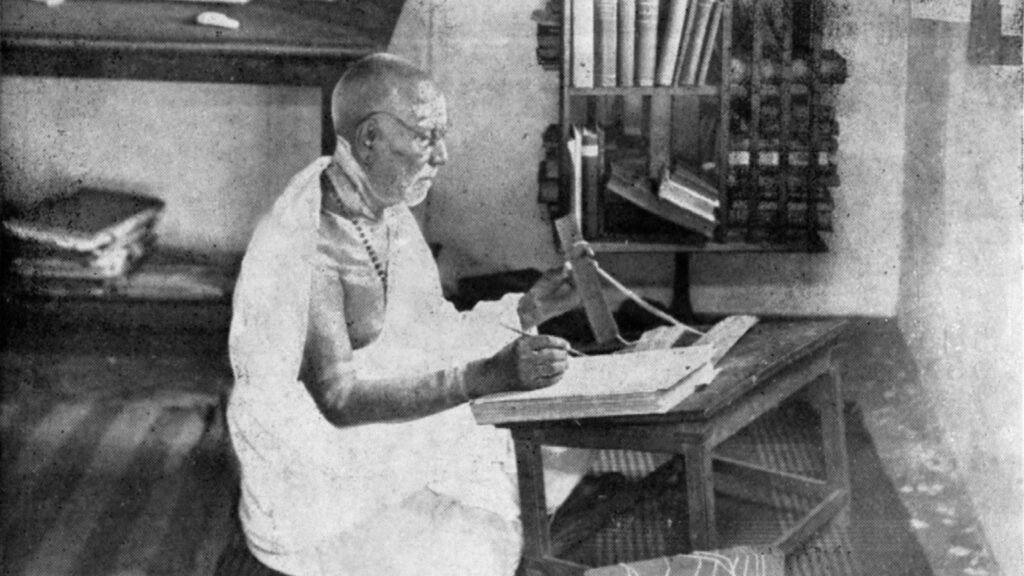

Unfortunately, Bose lost his wife, Toshiko, to tuberculosis in 1925. He raised his two children on his own, carried on with his revolutionary agenda in Japan and also took over the Nakamuraya bakery. He wanted to bring the flavours of the home he had left behind to Japan, and so he began to prepare dishes using Indian culinary traditions and spices in the restaurant.

As a passionate Indian in a foreign country and a true British adversary, you can imagine how heartbreaking it must have been for Bose to witness the karē raisu be enjoyed as a popular ‘Western’ dish in Japan, having lost all its authentic traits. He was determined to restore the dish to its true glory.

Nakamuraya became the only restaurant in Japan to sell authentic karē raisu, which was generously infused with ground spices. Its flavour and zing made the dish extremely popular, even though it was priced much higher than the humble curry that had made its way to the shores of Japan several decades earlier. Nakamuraya became one of the first ever food companies to go for initial public offering in the stock market.

Meanwhile, Bose continued to write in support of the Indian freedom movement, and went on to establish the Indian Independence League in 1942. This league would eventually be rallied under Subash Chandra Bose.

In 1945, the world lost the revolutionary chef. Bose succumbed to tuberculosis before witnessing India attain freedom. His legacy, though, lives on in the Nakamuraya bakery, which still exists in the Shinjuku area of Tokyo. And the karē raisu is still one of their bestsellers, because of its rich flavour and its even richer history.