Buddhism in India was in its golden age between the 4th century BCE and 6th century CE. The powerful Indian emperor Ashoka had converted to Buddhism after a life-changing event. He sent missionaries to spread the religion far and wide. Not long after that, Buddhism was patronised even by Hindu dynasties such as the Satavahanas and the Guptas, and it inspired unique contributions to art and architecture. Indian preachers took Buddhism to other parts of Asia too. But strangely, while Buddhism flourished elsewhere, it had almost disappeared in India by the 13th century CE. The grand art and architecture it had inspired lay forgotten under layers of earth… Until one man named Colin Mackenzie made a spectacular discovery.

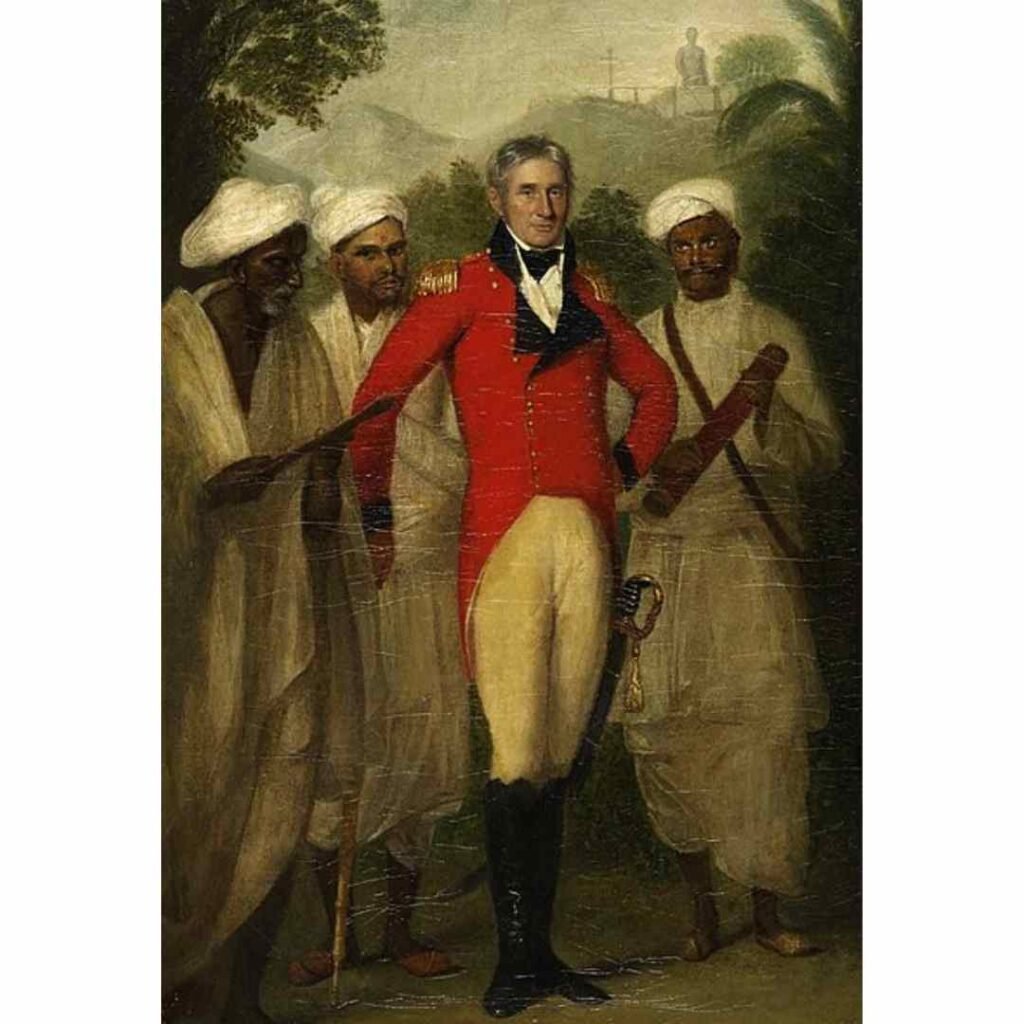

Born in an obscure Scottish town, Colin Mackenzie discovered early on in his life that mathematics fascinated him. While chewing his way through mathematical tomes, he came across the mathematics of the ancient Hindus and was spellbound. Only a trip to its roots in India would satisfy him.

He joined the army of the British East India Company, and because of his flair for numbers, he was appointed to the Engineering Corps. He arrived in India at Madras (present-day Chennai) in 1783, and soon became hooked to Indian art, culture and history. He was neither a historian nor an archaeologist, but in India, he took on both roles. He travelled throughout the Indian subcontinent documenting its history, literature and architecture. He sketched everything he saw and maintained detailed records. He also managed to collect and store important artefacts. In 1797, he travelled to Amaravati in present-day Andhra Pradesh, and discovered the remains of a stupa. By then, Buddhism had practically disappeared from India, and Mackenzie at first thought the ruins belonged to a Jain monument. But he was still on military duty, and found no time to explore the amazing ruin properly. So he notified his superiors about the find and moved on to other things.

Detour: Watch this short video for the story of the Buddhist relics of Amaravati

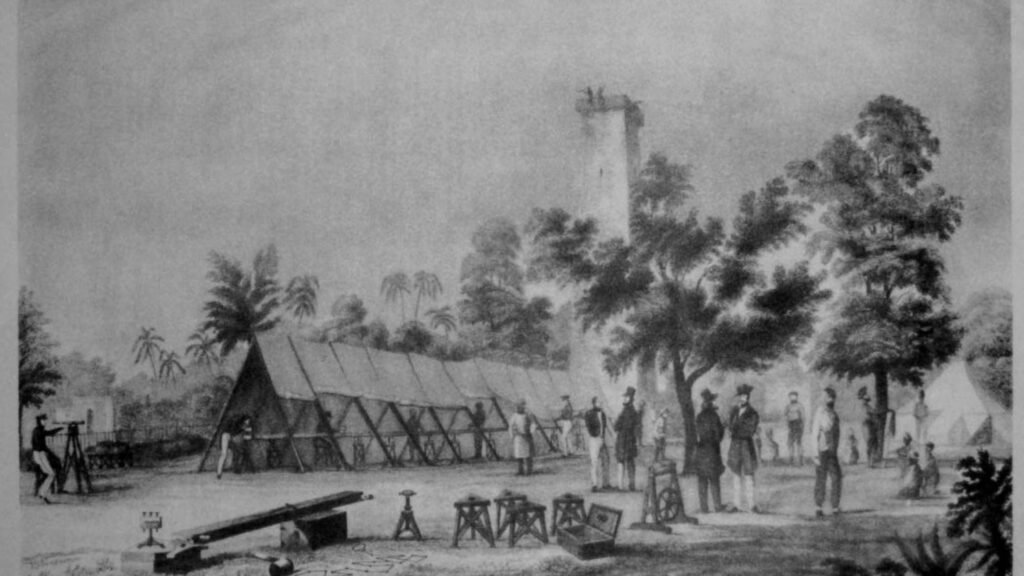

In 1815, Mackenzie was appointed the very first Surveyor General of India. Amaravati called to him again. But he was shocked to find that the site had declined rapidly. Bricks from the precious ruins had been carted away for building work, and irresponsible excavations had ruined the structure. He spent four years – between 1816 and 1820 – studying the ruins and deploring the neglect that had befallen them after his discovery. Mackenzie painstakingly excavated the site further and drew sketches and plans recreating the original structure.

But he didn’t manage all this on his own. A key factor in Mackenzie’s success was that he involved bright Indian assistants and directed them well. Early in his career, he recruited Cavelly Venkata Boraiah, an Indian scholar, and later his brother, Cavelly Lakshmaiah. They were fine researchers with a knack for getting inside information from the locals. Mackenzie’s team had at least 17 other Indian scholars.

Mackenzie spent nearly 40 busy years in India, passionately assembling around 1,568 literary manuscripts, 8,076 inscriptions, 79 plans, 2,630 drawings, 6,218 coins and many other antiquities – the largest collection of Indian artefacts owned by any European. He never returned home, and died in his adopted country in 1821. He left 5 percent of his estate to his dear colleague Lakshmiah and the rest to his wife. Mrs. Mackenzie discovered, to her horror, that all his savings had been spent on the collection. Desperate, she offered to sell the collection to the East India Company for Rs 20,000. When the company assessed the collection, they were astounded by its value. They paid a generous Rs 100,000 for it, and Mrs. Mackenzie retired comfortably.

Today, most of Mackenzie’s collection is in the British Museum or owned by the British Library. His discoveries from Amaravati, however, were moved to Madras (Chennai) some years after his death. You can see some of these beautiful treasures in the form of limestone carvings at the Amaravati Gallery of the Egmore Museum in Chennai. We now know that these artefacts are nearly 2000 years old, and this is the oldest Buddhist art collection in the world! They are called the Amaravati Marbles, but technically, these artefacts are not marbles at all. They are carved from a type of limestone called Palnad Marble. While they are both essentially calcium carbonate, unlike marble, limestone is porous and soluble in water.

The Amaravati artefacts are also displayed in the British Museum and a few other museums in India and the world. The World Corpus of Amaravati Sculpture is an international project that allows scholars of all nationalities to access information from museums and perform interdisciplinary research collaboratively. Thanks to one man, Colin Mackenzie, India and the whole world now share the joy of Buddhist art.