Have you heard of Ashoka the Great? Of course you have. The son of the Mauryan emperor Bindusara, Ashoka was a powerful ruler who reigned over most of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, over 2200 years ago. King Ashoka was also responsible for spreading Buddhism across large parts of Asia.

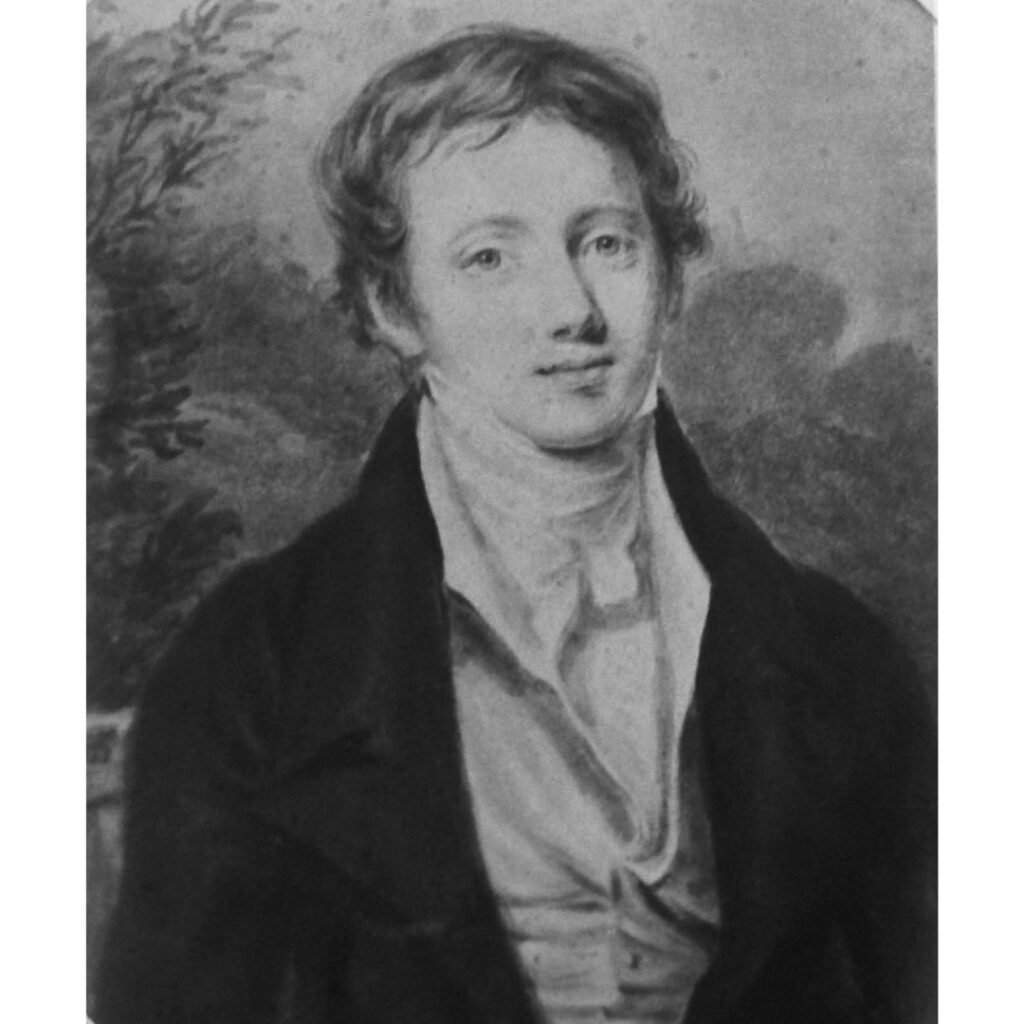

Now, have you heard of James Prinsep? Perhaps not – unless you are a diehard history buff. Well, he is the man who “discovered” the Mauryan king; it is because of his work that we know about Ashoka.

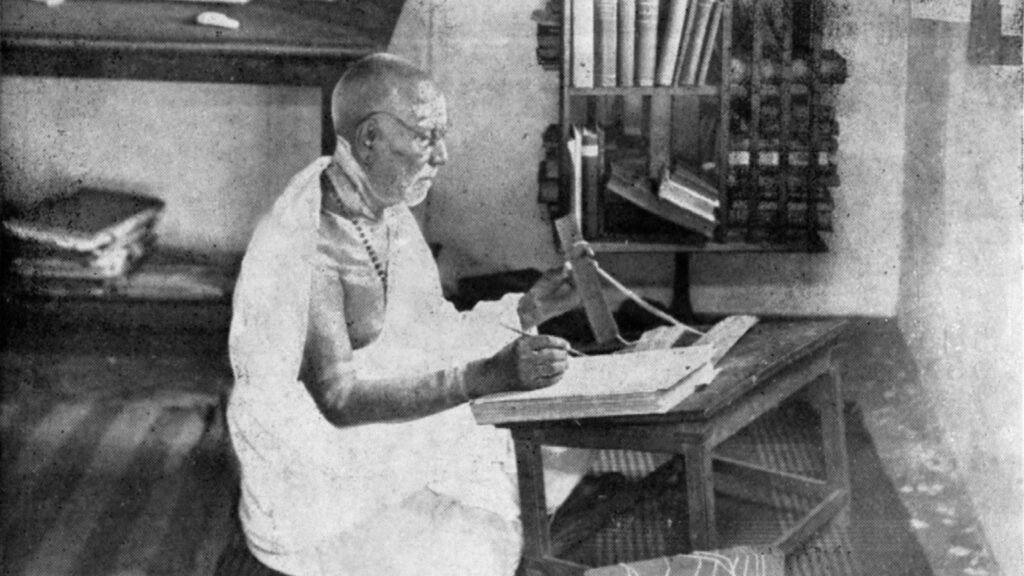

You see, Ashoka left behind a lot of information about his reign through inscriptions carved on stones, pillars and monuments. But these inscriptions were mostly in the Brahmi script, an ancient writing system which became obsolete by the 5th century CE. Over centuries, Indians forgot how to read them, and Ashoka’s history was lost.

In 1837-38, James Prinsep, an English Indologist, completed deciphering these inscriptions and restored Ashoka to his rightful place in history. Without Prinsep, we may never have learnt so much about the life of Ashoka.

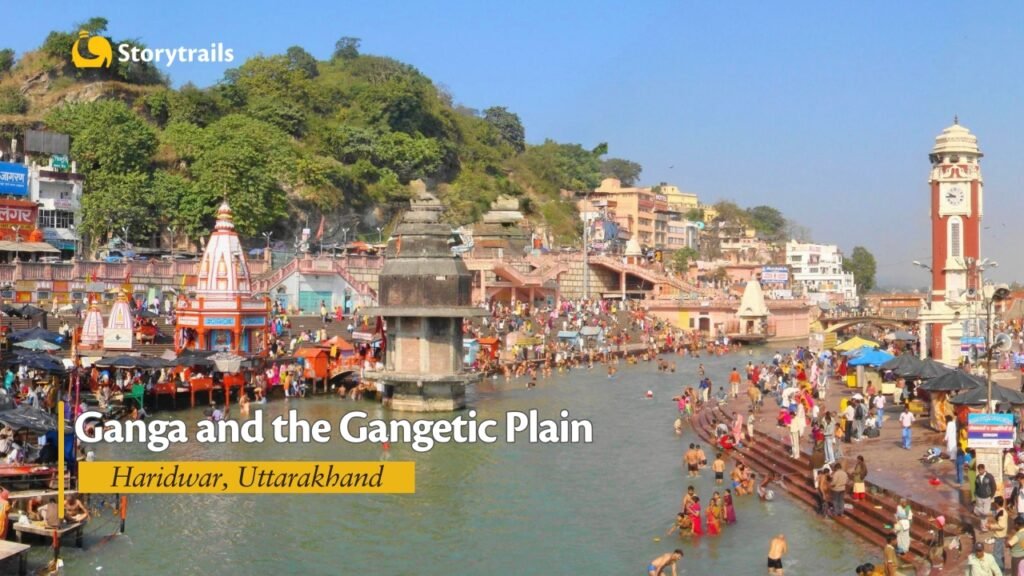

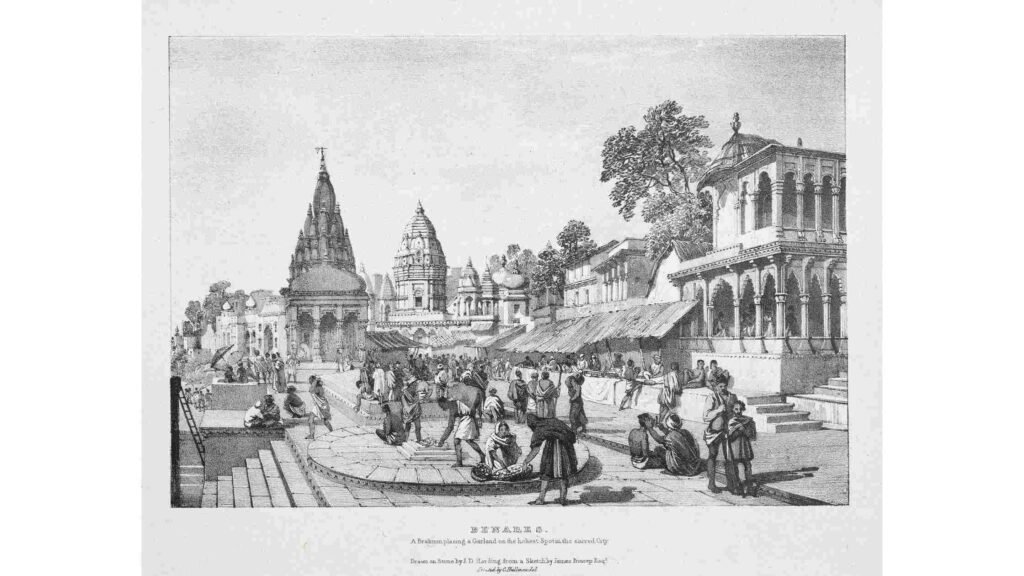

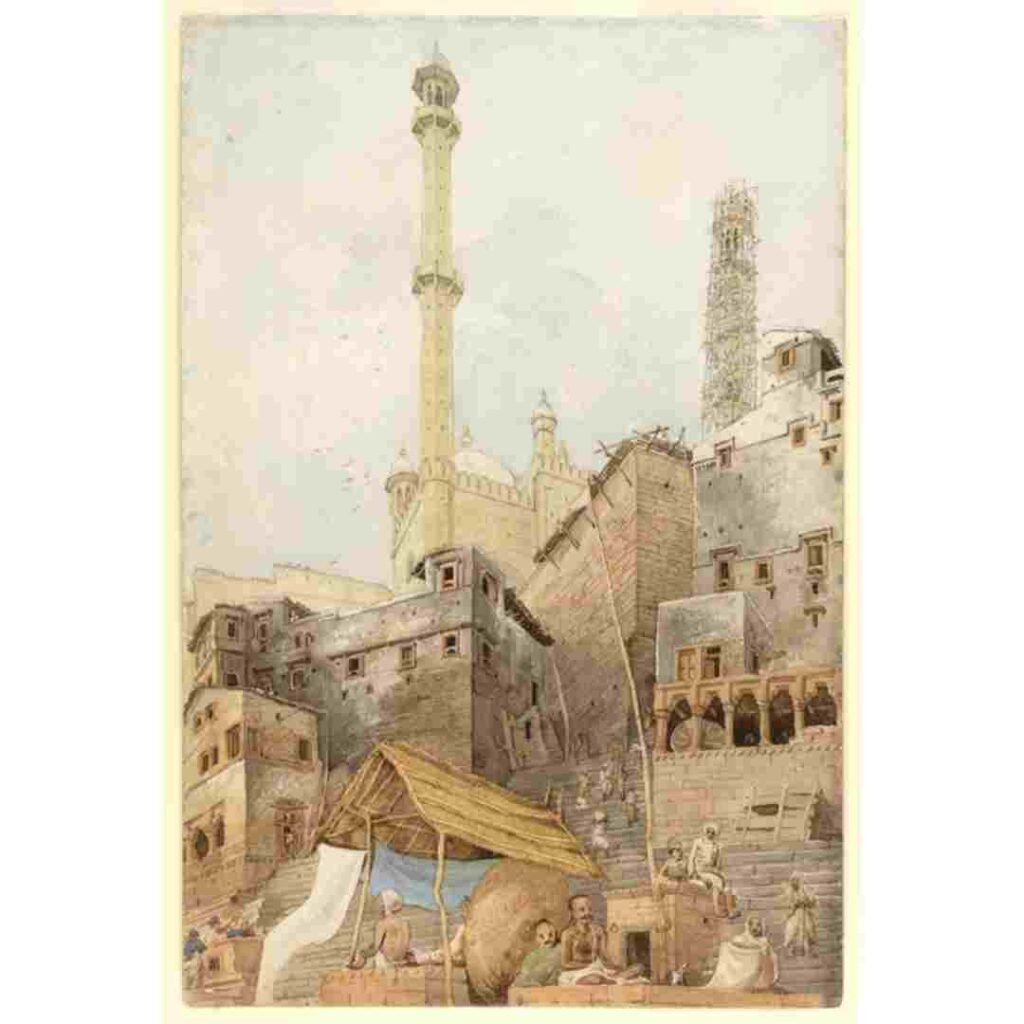

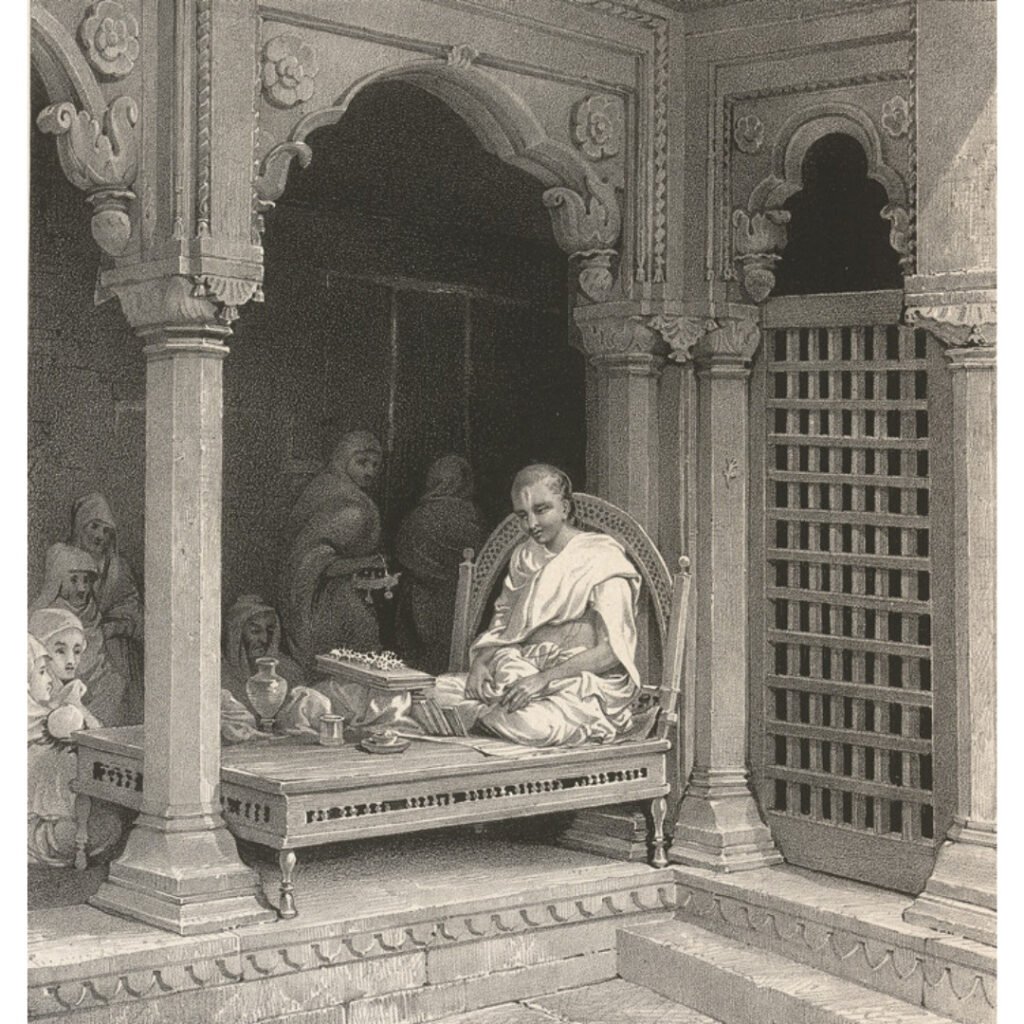

Prinsep did not start his career as an epigraphist; perhaps such a profession was unknown then. He wanted to be an architect, but an eye infection nearly blinded him. By the time he recovered, he had missed the opportunity. He came from a poor family and getting employed quickly was a necessity. Prinsep sailed to India in 1819 and joined the Calcutta Mint. Within a year he was posted as Assay Master of the Benares Mint. (An Assay Master of a mint is a metallurgical analyst, who tests the purity, weight and dimensions of a coin… essentially, the quality controller. This was no mean responsibility: unless the mint’s coins are metallurgically perfect, they can be counterfeited.) Sailing down the beautiful Ganga river, he was charmed by the country and became an Indophile for life. He produced brilliant collections of lithographs and watercolours about life in Benares. He painted with passion and sensitivity and had an eye for detail.

His old passion for architecture too got rekindled in India: he designed the new mint at Benares, built a church and even restored the endangered Alamgir Mosque minarets of Aurangzeb. He charted a map of Benares, redesigned its drainage system and built a bridge over the Karmanasa river. The people of Benares were ever grateful to him.

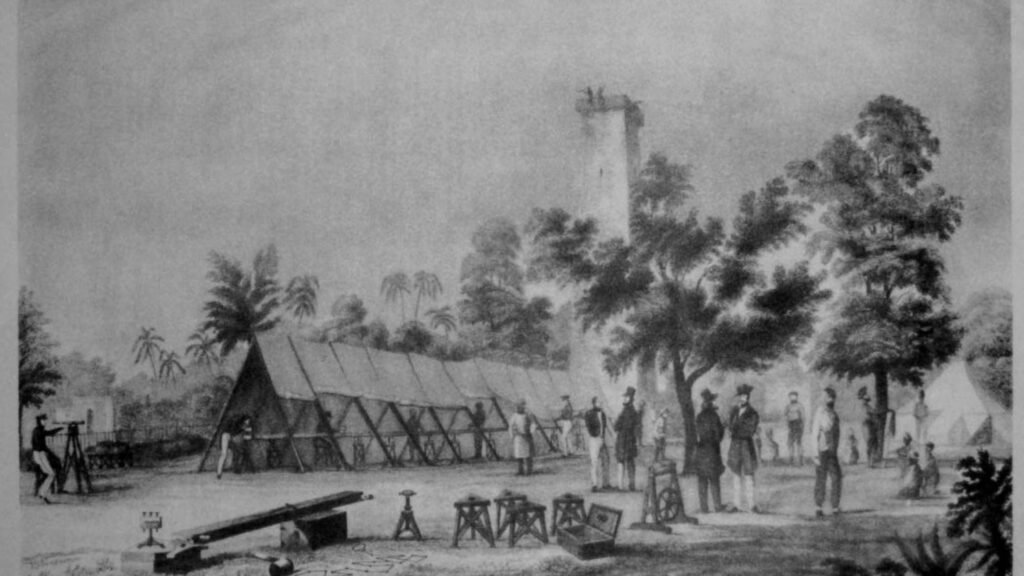

Amazingly, he accomplished all this while he was the Assay Master of the mint, where he executed his responsibilities most diligently. And he did much more! He published several scientific papers on metallurgical processes, for instance. His curious mind investigated all sorts of scientific phenomena. His research papers covered a wide range of subjects: meteorology, metallurgy, metrology, thermodynamics, astronomy, archaeology and palaeontology. Consider some of his achievements: the design of a micro-precision weighing balance, formulation of a gas mixture that could enable balloon flights, manufacture of a steam-powered ceiling fan, rust prevention methods on iron surfaces, and many more. The scientific community noticed him and elected him as Fellow of the Royal Society before he was twenty-nine years old. He became the editor of the Asiatic Society Journal by the age of thirty.

Soon, Prinsep was recalled to the Calcutta Mint. Calcutta was the capital of British India, a very “happening” place in those days. Besides being the Assay Master of the mint, he also became the honorary secretary of the Asiatic Society. His boss, Horace Wilson, who was a noted Sanskrit scholar and Indologist, encouraged him. And Prinsep got more opportunities to pursue his enduring love – numismatics. Being a Mint Master by profession, collection and analysis of coins came to him naturally. Moreover, given his status in the Asiatic Society, people kept sending him coins and artefacts for analysis; this sharpened his expertise. In fact, a large part of his coin collection is on display at the British Museum even today! Numismatics led Prinsep to another intellectual pursuit. He was fascinated by the inscriptions – in different languages and scripts – on the coins. This drove him to philology, the study of languages, and epigraphy, the study of scripts. Soon he had taught himself both these sciences. Slowly, he solved the mystery of the Ashokan edicts by deciphering the Brahmi script, and earned himself a permanent pedestal in Indian history!

Detour: Watch this short video for the story of how the Brahmi script was decoded.

Prinsep was also instrumental in decoding another language called Kharosthi. It was a language that was used in NW India, Pakistan, East Afghanistan and parts of Central Asia. It was in vogue roughly between the 4th century BCE and 3rd century CE, when Indo-Greek rulers ruled over these parts. And then it became extinct. Prinsep got interested in this script because some of the Ashokan inscriptions were in this language. As a numismatist, Prinsep had noticed that some ancient coins were bilingual coins: the inscriptions on them were in two languages. Prinsep’s collection included bilingual coins, which were inscribed in Greek and Kharosthi. He rightly guessed that the message in both the languages was usually the same; he was fluent in Greek, so he used that knowledge to crack the Kharosthi script.

Then came the tragedy. For nearly 20 years, Prinsep had been driving his frail body to perform great feats in arts and sciences. His exhausted body collapsed. He was plagued by mysterious headaches. He returned to England to find a cure, but his illness worsened. He died in 1840, barely 41. When it came to his own life, Prinsep could not see the writing on the wall

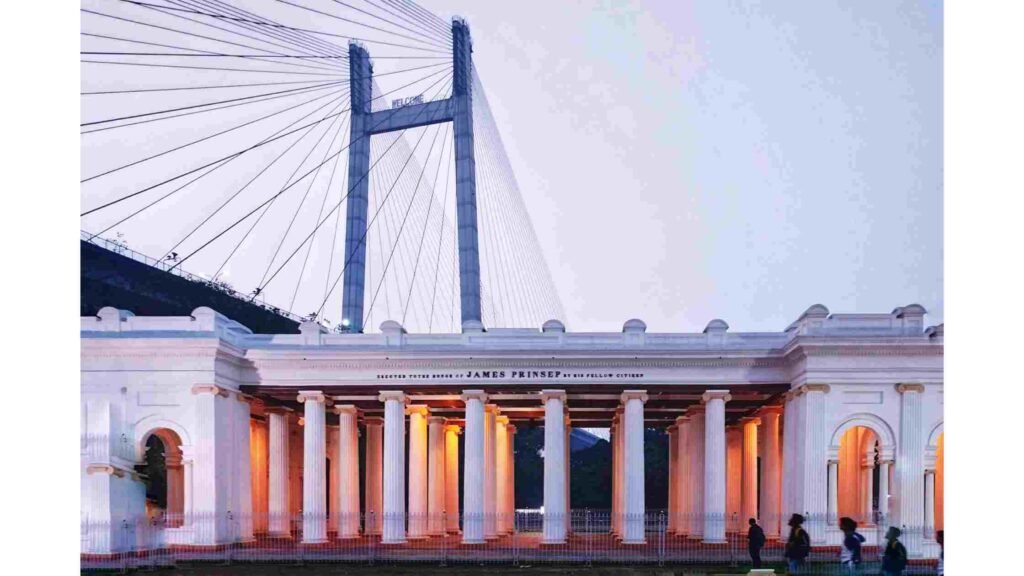

The grateful citizens of Calcutta raised a memorial, called the Prinsep Ghat, for him on the banks of River Hooghly (ghat means “steps leading to a river”).

Post script

Did you know that one genus of plants in the Indian subcontinent is named after Prinsep? It is called Prinsepia.