The resurrection of Jeevaka Chintamani

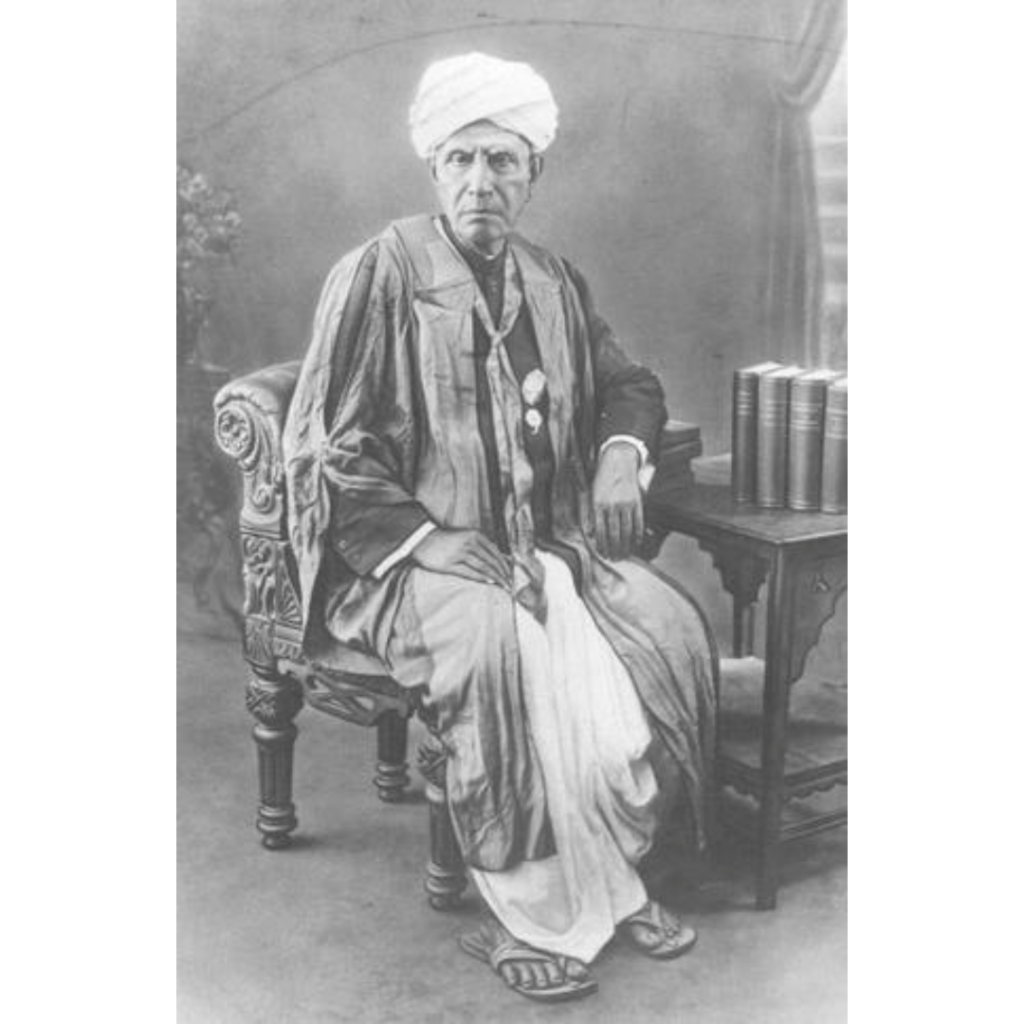

Jeevaka Chintamani, considered to be one of the five greatest ever Tamil epics*, is a 10th-century classic composed by the Jain monk Thiruthakka Thevar. It was a forgotten treasure till Dr. U.V. Swaminatha Iyer (also called UVeSa) rediscovered and assembled the complete manuscript after a statewide hunt that lasted many years. He then breathed life into many other literary classics, reviving the lost glory of ancient Tamil literature. Here is how it happened.

The challenge

Swaminatha Iyer was a Tamil professor at the Kumbakonam Government College, who had studied at a Hindu monastery (Thiruvaduthurai*) which also nurtured Tamil literature. Salem Ramaswami Mudaliar was a munsif (junior judge) in the British Raj, and a great connoisseur of Tamil literature. It was a conversation between these two that sparked UVeSa’s quest.

One day, Judge Ramaswami taunted UVeSa saying, ‘What do you know of the ancient classics? Can you even annotate the Jeevaka Chinatamani?’

This was in the 1880s, when Tamil scholarship had fallen to a new low. Macaulay-inspired English institutions had begun dominating India, and vernacular studies languished. Tamil pundits taught literature that was, at the most, 250 years old. Classical Tamil literature – with a 2000-year-old legacy, shaped by highly sophisticated grammar and subtle poetry – was almost unknown. Printing technology had come to India by the 16th century, but very few Tamil classics were in print.

Stung by Ramaswami’s challenge, UVeSa was determined to produce a complete research paper on the subject. In order to help him kick-start the project, Ramaswami gave him a transcript with a commentary on the epic by a 14th-century scholar named Nachinarkiniyar.

The ‘fake’ manuscript

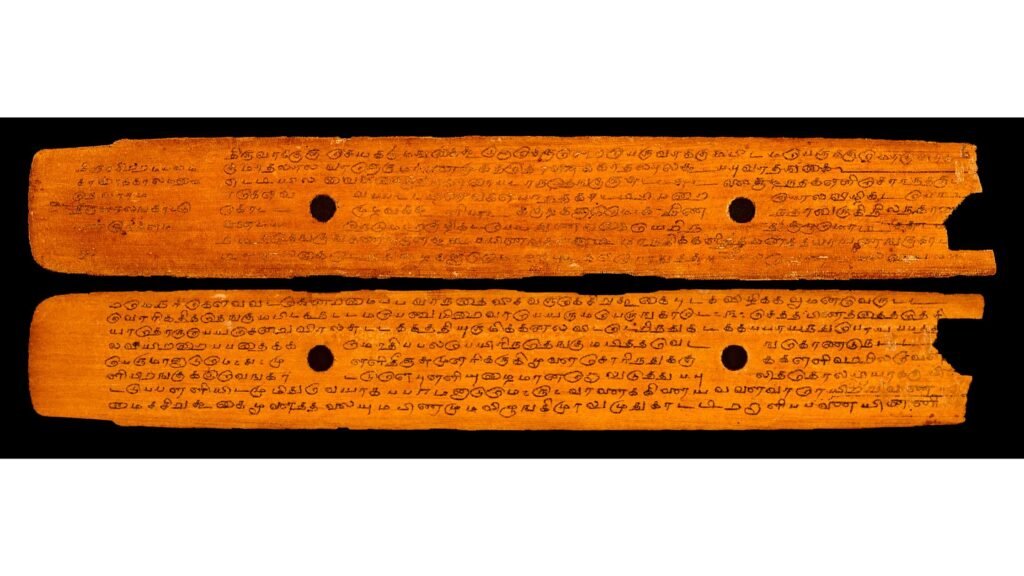

Intuitively, Uvesa rushed to his alma mater, the Thiruvaduthurai monastery, to find references to Jeevaka Chintamani. He scoured its vast library and found another manuscript of the commentary by Nachinarkiniyar. Oddly, the two versions did not match. How could two commentaries by the same author on the same subject be different? Before we go further into the story, we need to go back in time to understand ancient manuscripts. How did 2000-year-old literature get passed down from generation to generation before printing technology evolved? Through olai chuvadis or treated palm-leaf strips that were inscribed with a metal stylus called ezhuthani. The writer had to ‘scratch’ the words with great care and precision – too much pressure would destroy the leaf, too little would make it unreadable! Depending on the environment and the preservation process it could last even 500 years, but the typical shelf life was about 100 years. How could a 100-year-old medium store 2000-year-old information?

Well, the ancient Tamil kings were great patrons of art. Apart from encouraging authors, they also employed skilled copyists to copy literary pieces from decaying palm leaves to fresh palm leaves. The new copies were then distributed to nobles and the rich patrons. These patrons (or their descendants) made fresh copies when the current palm leaves faded.

This co-operative chain was disrupted when the Europeans colonised India. Society changed, and fewer people were interested in ‘reprinting’ these manuscripts. Old manuscripts lay hidden in the attics of families who had forgotten their value. With fewer manuscripts in the public domain, even professors taught only ‘recent’ writings, not the classics. This was the crux of the Ramaswami–Uvesa conversation.

Searching for a copy of a 1000-year-old epic was pretty much an impossible task. Obviously, the ‘original’ had vanished centuries ago. Different parts of the epic lay in different households, and not in any particular sequence. The merit of even those was dependent on the copyist. One different stroke on the palm leaf could convey a meaning very different from the intention of the original author. And then there was the problem of fakes.

The Jain Culture

Today there are less than 1,00,000 Tamil Jains. But a millennium ago, they were a prosperous community who made outstanding contributions to art and literature. Even in UVeSa’s era, there were many people who practised Jain traditions. He decided to meet some of them to learn about Jain customs. How could he write a commentary on a Jain text if he did not understand the social, cultural and religious context?

UVeSa trained under Chandranatha Chettiar, a pious Tamil Jain, for several months. After exhausting everything he knew, Chandranatha introduced him to Gunabala Chettiar, another expert in Jain tradition. Mrs. Gunabala was a greater expert in Jain tradition and eager to help.

That’s when UVeSa discovered a startling fact. Nachinarkiniyar, the 14th-century commentator, had indeed written two commentaries. The second commentary was written after he had enrolled in a Jain monastery and studied Jain tradition closely. This proved that the two versions UVeSa had were both genuine. It also validated Uvesa’s approach: you cannot annotate any literary piece without knowing the context!

The Hunt

UVeSa was now confident that his preparation was good. He had two versions of the commentary. Now he had to assemble all the ‘authentic’ palm-leaf manuscripts of the entire Jeevaka Chintamani – all 13 volumes comprising 3,147 verses. The only way was to round up all the known versions and compare every line in every version. Thus began his long journey, which lasted around seven years. It was a house-to-house campaign which touched even the smallest villages in Tamil Nadu. Sometimes the inquiries in one village would give a clue about scripts in another village, and off he went to that village. In many private collections, he had to wade through hundreds of un-indexed palm leaves, only to return empty-handed. In some cases, he found that the owner had very recently burnt the palm leaves or thrown them away into a river as a ritual cleaning! Sometimes the owners even refused to cooperate.

Some days were fruitful, many days were depressingly disappointing, and all days were exhausting. Ultimately UVeSa had 23 ‘clean’ manuscripts that had been tallied and validated. He was now ready to compile and publish!

Publishing Perils

Now publishing had to be done from the provincial capital, Madras. It needed big money and patronage; academic brilliance alone was insufficient. Was Uvesa, who was barely in his 30s, equal to the task? This was the poser of Thamotharam Pillai, a Sri Lankan patron who pressured Uvesa to sell the copyright to him. For a moment, Uvesa was tempted; but he did not yield. Uvesa wanted to be in full control of the complete process. With promises of funding by Judge Ramaswami and other patrons, Uvesa prepared to publish on his own.

There were discouragements galore. The news that a Tamil scholar from Jaffna was already about to publish a treatise on the same epic created a scare – such competition could ruin Uvesa financially; mercifully, it turned out to be a baseless rumour. Another ‘well-wisher’ warned him not to take up Jeevaka Chintamani — many veterans had failed at this project, so why should a smart young man stake his reputation on this? Midway through the project, Uvesa exhausted his personal funds and had no money even to buy paper. In a divine twist of fate, Thamotharam Pillai (the man who had earlier pressured him to sell his copyright) intervened and got him supplies on credit; he turned out to be the Good Samaritan!

Recognition at Last

In 1887, Uvesa released the first edition of a few hundred copies. It was a near-perfect translation of the forgotten masterpiece; his annotation wonderfully established its social-cultural-historical-religious context. UVeSa had beaten the odds – and he was just 32!

His troubles were far from being over, though. At his alma mater, one priest protested: ‘How could the student of a Hindu monastery publish a patently religious Jain text?’ The head monk silenced him by saying that UVeSa had brought great honour to the monastery by publishing an ancient work of art. Some ultra-conservatives condemned the erotic passages in the work. UVeSa calmly replied that the epic covered a range of human emotions; a true connoisseur would notice the artistic merit of the lines instead of carping on their sexuality! Those were puritanical times, yet UVeSa had won the overwhelming support of the liberals.

Thus encouraged, he published his research on two other epics – Silappadikaram and Manimekalai, and the Sangam-era Puranaanuru, which reflected the culture of ancient Tamils. Ultimately, he published nearly 100 books, a remarkable achievement for any researcher. The ultimate appreciation was the epithet he earned – ‘Thamizh Thatha’ or the ‘grand old man of Tamil’.

*The 5 great Tamil ancient epics are Silappadikaram, Manimekalai, Jeevaka Chintamani, Kundalakesi and Valayapathi.

Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam (monastery) was established around the 16th century to spread Saiva philosophy. It manages many Siva temples and has a large library of ancient religious literature.