Most of us know about Ponniyin Selvan – a fictional account woven by the author Kalki Krishnamurthy around the ascent of Rajaraja I, the powerful Chola emperor of the 10th -11th century. It has love, war, intrigue and more – in short, it’s blockbuster material. No wonder, Kollywood director Mani Ratnam made a two-part film saga out of it. In the novel, many of the women characters are portrayed as strong, decisive and influential. Was that characterisation purely Kalki’s imagination? Were the women in the Chola era – a thousand years ago – as empowered as he made them out to be? Kalki’s commentaries often criticised gender/caste prejudice and promoted women’s education and emancipation. So did he paint his fictional characters with this same idealistic brush? Let us take a look at the real lives of two of the royal ladies in the novel.

Sembiyan Mahadevi

Rajaraja held his grand-aunt Sembiyan Mahadevi in the highest regard. In her lifetime she interacted with six kings in her family and greatly influenced the life of two more scions. She became queen by chance and held office for just six years (c. 950-956 CE).She survived the tragedy of her husband’s and son’s deaths, and stood tall among all these royals.

Her father-in-law, Parantaka I, was an expansionist ruler who had made the Cholas very powerful. Unfortunately, his eldest son, Rajaditya, predeceased him in a battle. The new heir apparent was his younger son Gandaraditya, Sembiyan Mahadevi’s husband. When Parantaka I died in 950 CE, Gandaraditya became king and Sembiyan Mahadevi the queen. She was definitely queen material, but was Gandaraditya king material? During his reign he lost the bulk of the Tondaimandalam territory to the Rashtrakutas. Gandaraditya lacked military zeal and his talents lay elsewhere. Deeply religious, the hymns he composed were recorded in the 9th volume of Thirumurai, which even today is regarded as the most sacred book of the Tamil Shaivites (Shiva worshippers).

For many years Gandaraditya had no male heir. And then, quite late in life, Sembiyan Mahadevi delivered a boy – Madurantaka aka Uttama. Gandaraditya was already getting on in years and he co-opted his younger brother Arinjaya into the administration. When he died around 956 CE, it was Arinjaya who succeeded him and not Uttama, who was still an infant. The ageing Arinjaya himself died in about a year. Uttama was still an infant, so Arinjaya was succeeded by his son Parantaka II (aka Sundara Chola). And he, like his namesake ancestor, was a military leader; he retrieved all the lost Chola territories.

Now, what was Sembiyan Mahadevi’s life like through all this? Like her husband, she too was deeply religious. This was not an idle sentiment, but something that gave her a sense of purpose. She was dedicated to renovating old temples, building new ones and initiating public works. She did more with Gandaraditya’s support, when he became king. When Gandaraditya died, her options seemed limited. She could commit sati, but she had an infant son to bring up. Or she could quietly retire into the Andapuram (female quarter of the palace). She did neither. She decided to pursue her passion for religious and social activism for the next 50 years. She not only became a popular dowager queen but also the go-to matriarch of the Chola family.

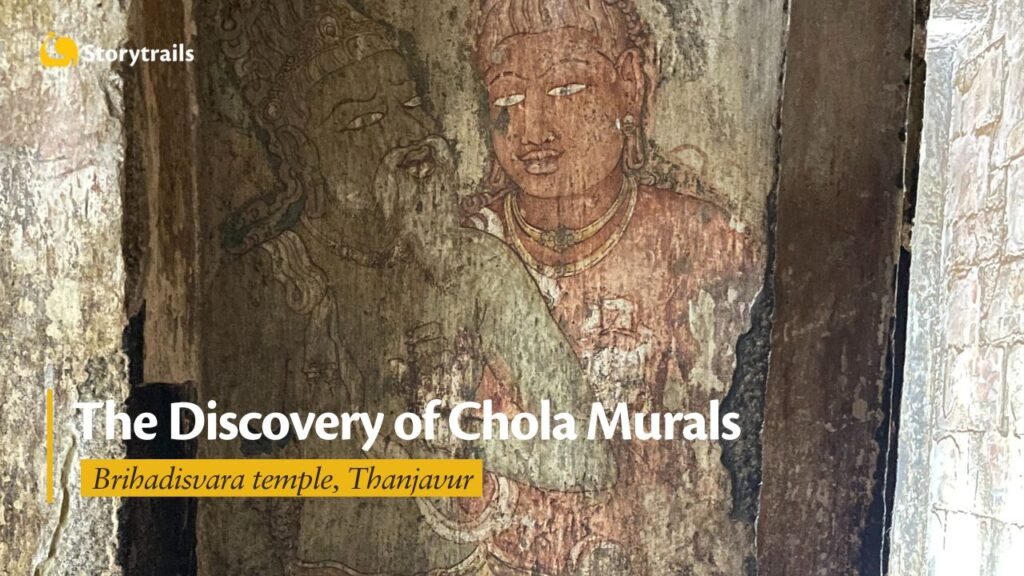

She was a pioneer in Kalpani (literally ‘stone-work’) or projects involving conversion of old temples of brick and mortar into endurable granite temples. She had a farsighted appreciation of history – she ordered that the ancient inscriptions be copied first before reconstructing the temple in granite. The temples and icons commissioned by her had her unique stamp. She donated jewels and bronzes to many temples – many commissioned by her, others by her family members like Rajaraja and Uttama. That she was popular is evident from the fact that many villages and public works were named after her. This is a Chola bronze of the 10th century which portrays her as goddess Parvati herself.

Princess Kundavai

The other strong Chola woman was Kundavai Pirattiyar, Rajaraja’s elder sister. She was married to Vallavarayan Vandiyathevan, the Bana ruler of Brahmadesam, a feudatory of the Cholas, and also a powerful commander of the Chola army. She did not, however, move to the Bana kingdom but stayed mostly at Pazhaiyarai. Pazhaiyarai was the second most important city of the Cholas (after Thanjavur) and a second home to the Chola family. From here she chose to serve public causes. She contributed gold and jewels to the Brihadeeswara Temple, which was close to her brother Rajaraja’s heart. The temple inscriptions describe them in great detail; in fact, her contributions appear ahead of the contributions of Rajaraja’s queens.

Detour: For more on the wonders of the Brihadeeswara Temple, listen to our podcast:

Kundavai’s contributions were not just limited to Shiva temples but also to Jain and Buddhist temples as well – the most important being the Jain shrines of Darasuram (or Rajarajeswaram) and Tirumalai (near Tiruvannamalai). She gave away lands for building hospitals, and donated money for irrigation projects – like the Kundavai-pereri at Brahmadesam.

Rajaraja’s queens too enjoyed enormous autonomy. For example, we have evidence that Logamahadevi, one of Rajaraja’s queens, employed a high-ranking women officer titled ‘adigaracci’ only to manage her endowments. Chola royal women were highly educated, had economic independence and financial authority, sponsored arts and initiated welfare projects – all in their own (not in their husbands’) names. So, Kalki’s characterisation of women in Ponniyin Selvan was realistic!

Chola women probably had considerable influence in national policy matters too. This though is more difficult to prove without some extrapolation. One of the most enduring mysteries from that time is why Rajaraja Chola did not ascend the throne in 970 CE when his father died.

He had all the qualifications, plus the support of the nobles and masses. Instead, he declared that he supported his uncle Uttama’s candidature, and would work as his deputy. Uttama was sedate, pious and conservative. But Rajaraja was an expansionist ruler and a progressive-change agent. Why did he volunteer to work backstage?

Some scholars believe it must have been the influence of Sembiyan Mahadevi and Kundavai. They had probably sensed that Uttama wanted the crown badly. As a late addition to the family, Uttama had missed the crown thrice. Rather than harbour simmering discontent, if he was given a shot at the throne he would actually warm the seat while young Rajaraja matured.

Detour: Read more about how the mysterious circumstances in which Rajaraja Chola became king inspired Kalki’s masterpiece, Ponniyin Selvan, here.

The two ladies could have hammered a deal in the last days of Sundara Chola whereby Uttama would succeed him, but he would hand over the reins to Rajaraja after that; and Uttama’s children would have no claim ever. And this is what exactly happened. Uttama ruled for 15 years, and died quietly (and conveniently). Rajaraja who was in the side-lines till then blossomed into a dynamic ruler. Uttama’s son, Madurantaka Gandaradityan, quietly faded from public life. The deal succeeded because of the high influence of Sembiyan and Kundavai within family circles. If this hypothesis is true, the Chola women basically engineered the greatest constitutional re-arrangement in Chola history!

Detour: Did you know that Rajaraja’s son, Rajendra Chola, is considered to be the greatest among the Chola kings? Watch this short video for his story.

PS: Sati was not a standard operating practice in Chola tradition, though some queens practised it. For instance, Queen Vanavan Mahadevi, Sundara Chola’s wife, practised sati in 970 CE. So did Queen Viramahadevi, when Rajendra Chola died in 1044 CE.