A Chola gift to Chennai

The opening scenes of the film adaptation of Kalki Krishnamurthy’s Ponniyin Selvan vividly describe the natural beauty of the Veera-narayana Mangalam Lake. Kalki wrote the book around 1950. Little did he know that this lake would continue to create history in independent India. Situated about 235 km south of Chennai, it now supplies about 25% of Chennai’s water (up to 180 million litres per day). Most Chennai citizens cannot recognise the name, because they know the lake only by its bastardised name – Veeranam Lake! Agreed, Veera-narayana Mangalam is quite a mouthful, but ‘Veeranam’ gives little credit to its glorious history. Here’s the full story.

It is one of the largest manmade lakes in India. In the 1960s, the state government planned to pump water from this distant lake to Chennai through a network of pipes. But the project was plagued with errors of omission, commission and corruption. After a colossal delay (about 35 years!), it finally fulfilled its objective, although cost overruns were humongous. This was in stark contrast to what the Cholas did with the same lake.

It was constructed during the reign of the Chola king Parantaka I (r. 907-955 CE). Parantaka was an early ruler of the Imperial Chola dynasty and a champion of the Chola renaissance. He subjugated the Pandyas and Cheras and defeated the Rashtrakutas; his extended empire included northern Sri Lanka too! Parantaka realised that any of these territories could rebel against him at any time, so he maintained a huge standing army. Later, Crown Prince Rajaditya (Parantaka’s first son) became the commander of this army.

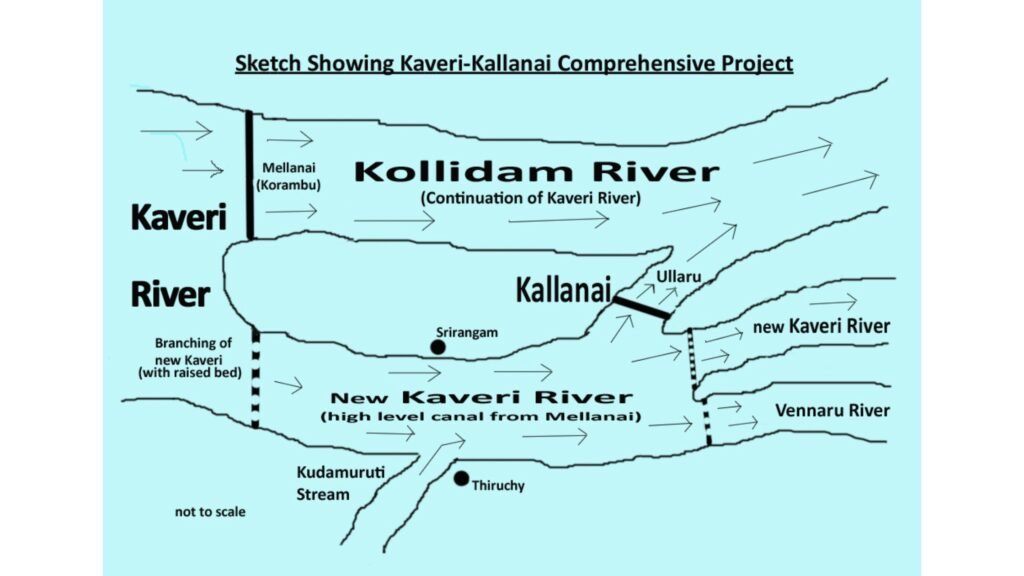

Once, when Rajaditya’s army camped in this area, he came up with the idea of building this huge lake (estimated to be about 140 sq. km then) here. He would fill the lake with a diversion from the gushing river Kollidam. Where would he get the manpower for such a mega project? The Imperial Chola Army, of course. On the face of it, it seems a bit strange to use the army for civil engineering. But Rajaditya was killing two….no, four birds with one stone. Let us analyse the strategic thinking that could have crossed his mind.

Bird 1: It is difficult to keep an army together during peacetime. Soldiers are professionals who kill for a ‘noble’ cause; without that cause they could go berserk. The hydraulic works of Veeranam would keep them focussed on a patriotic cause, till a more patriotic cause (like defending the borders) came up.

Bird 2: Rajaditya noticed that the waters of the river Kollidam, a distributary of the river Kaveri, were uselessly flowing into the Bay of Bengal. (Remember, this was a millennium before the Mettur and Mysore dams had been built.) During some monsoons it would flood towns and create further losses. So, the turgid Kollidam was a huge untapped water resource.

Bird 3: The main source of national income in those days was agriculture. A reservoir like this would increase the acreage of arable land under irrigation and boost agriculture. And in times of emergency, it would provide food security in the empire.

Bird 4: Public projects like this would generate more employment opportunities down the line. That would keep people happy and pro-government.

Rajaditya named the lake Veera-narayana Mangalam, because that was his father, Parantaka’s pre-coronation name. Unfortunately, Rajaditya did not live long to enjoy his pet project. The ‘higher’ patriotic cause that the Chola army had been waiting for emerged when the Rashtrakutas attacked in 948 CE. Rajaditya led the Chola army into battle at Takkolam (near Arakkonam), where an enemy arrow pierced him, killing him instantaneously. With their commander dead, the Chola army broke into disarray. And then it took two generations for the mighty dynasty to recover from that loss.

India’s oldest functioning dam

There is no denying that the Cholas were great hydraulic engineers – both in conceiving and executing projects.

Here is another example from eight centuries earlier. King Karikala Chola was an early ancestor of the Imperial Cholas. He ruled over the Chola kingdom around the 2nd century CE (historians are not sure about the exact dates, and the 2nd century is our best estimate). He first defeated conspiring usurpers who had staked illegitimate claims to the throne. Then, he routed the combined Chera and Pandya armies, who tried to take advantage of the brief uncertainty in Cholas’ domestic politics. Later, he went to Sri Lanka and defeated their army, and is said to have come back with an estimated 12000 slaves.

He built a remarkable dam on the Kaveri river, about 145 km to the south of Veeranam. It is called Kallanai, which literally means ‘Stone-dam’ in Tamil. The Kaveri 1800 years ago was an undammed, forceful river, and Karikalan realised that if at least a part of the river was harnessed instead of letting it flow into the sea, dramatic results would follow. The question was: how?

The location chosen for the dam was strategic. It was after the Kaveri and Kollidam rivers encircled the Srirangam island and re-joined but before splitting again into Kollidam, Kaveri, Vennaru and Puthu-aru. The Chola engineers did not build a conventional dam that blocked the entire flow to create a reservoir, but built a check-dam. The check-dam diverted the flow of water which was previously flowing from the Kaveri into the Kollidam, back to the Kaveri on the south bank. Consequently, this fed man-made canals that would irrigate fields south of the river. Moreover, if the Kaveri overflowed, the surplus water would get discharged into Kollidam.

The genius of Chola engineering was not to work AGAINST the force of nature, but to work WITH the flow of the river. The check dam is made entirely of stone boulders, cut and interlocked. There were no binders like cement or concrete then, of course, so they simply cut the stones, placed them on the sand-bed, wedged them and bound them with clay and plant material. The dam is 329 metres long, 20 metres wide and 5.4 metres deep. That was a lot of material for that time and needed a huge labour force to install in a turbulent river. So where did the workers come from? Remember the slaves from the Sri Lanka war? That’s where they were put to work.

The effects of the dam were immediately felt. It is estimated that roughly 280 sq. km. of land were additionally irrigated, and that made Chola country the rice bowl of India. Many centuries passed, and the dam served the public with very little maintenance. In 1829, the British deputed a brilliant military engineer named Sir Arthur Cotton to improve the irrigation facilities of the Kaveri region. When he visited Kallanai, he was amazed by the engineering and renamed it the Grand Anicut (derived from the Tamil “Anaikattu”, meaning dam). He said the dam would stand for centuries and needed no renovation. He went on to add the Lower Anicut dam on the Kollidam river, using the same principles, but with modern technology!

Another Chola gift

Chennai citizens can thank the Cholas for another huge lake – the Chembarambakkam lake that can supply 500 million litres per day. It was built by Rajendra Chola I (r. 1014-1044 CE). It is not fed by any river (unlike Veeranam) but was designed to harness monsoonal rains in the adjacent catchment area. In fact, Chennai’s Adyar river originates from this lake, and discharges surplus water.

Detour: Rajendra Chola I is widely believed to be the greatest of the Cholas. Watch his story here:

The Cholas made massive public investments in water resource projects. We have lost many of them due to urbanisation, illegal settlements, unchecked sedimentation, insensitive plastic pollution, and so on. A case in point is the Singena Agrahara Lake (aka Narayanaghetta Kere), about 20 km. from Bengaluru. Two years ago, a retired-army-officer-turned- social-activist helped in rejuvenating this ruined lake, to help flood control and irrigation. Who was the original sponsor of the lake? Rajaraja Chola I (r. 985-1014 CE)! The Cholas left a legacy that outlasted them by over a thousand years!