Some of the oldest art in India, dating back to the 1st century BCE, can be found in the Ajanta caves of Maharashtra. These caves and their paintings were created not long after the death of Buddha under the patronage of a dynasty called the Satavahanas, a dynasty that ruled for over three centuries and greatly influenced Indian art. Who were they, how did they come to power, and what made them so successful? Historians don’t have definitive answers yet.

But a 2,200-year-old pot that can be seen in Naneghat pass in Maharashtra’s Western Ghats holds a clue.

Many Satavahana sites have fallen to ruin. And the archeological evidence and literary references to the Satavahanas do not always match up. Take for instance, the Matsya Purana, an ancient text about Indian polity, society and art that refers to the Andhra dynasty. Some historians believe that the location of the Andhra kingdom matches Satavahana territory. So they conclude that it must be the same dynasty. Others insist that the Puranas date the Andhras two centuries before the earliest evidence of the Satavahanas. And therefore, they cannot be the same.

What do we know about the Satavahanas?

So, what can we say with certainty about the Satavahanas? Around 180 BCE, when the great Mauryan Empire broke up, their feudatories quickly filled the vacuum. The Satavahanas, perhaps the most enterprising feudatory, carved a large empire. Their territory included Andhra, Telangana and large chunks of Maharashtra. Often, under many enterprising Satavahana kings, the territory extended to North Karnataka, Gujarat and parts of Madhya Pradesh. That was the entire Deccan region of India, plus a lot more. The Satavahanas were the first major Deccani dynasty who ruled for nearly four centuries.

How did the Satavahanas become so great?

They almost certainly had a powerful army, and they inherited many governance systems from the Mauryas. But the single most important factor was that they owned a crucial piece of geography. Their territory included the Krishna, Godavari and Narmada river basin regions where agriculture flourished. Not only was the land fertile, but its location was also strategic. They were right at the centre of the Indian subcontinent, and their empire stretched from coast to coast. The western ports like Kalyan and Sopara received Roman, Arabic and Egyptian trade; from the east coast Indian merchants traded with the Far East; and from all these ports there was a huge trade with the hinterland. Any North-South trade in the subcontinent had to necessarily pass through Satavahana territory. Busy commercial towns sprang up all along the trade routes. Professional guilds nurtured the growth of crafts and industry. Indeed, the Satavahanas were an economic superpower.

All this meant that the government earned huge revenues from taxes collected at ports and domestic trade routes. Travellers would pay tolls at various points in the kingdom. A prominent tollgate was the Naneghat pass in the Western Ghats in Maharashtra. This pass essentially made the journey between the rest of India and the North-Western coast considerably shorter. At Naneghat you can still see the remains of a pot that archaeologists believe was used to collect tolls from travellers and merchants. In nearby caves there are remnants of monuments that honour Satavahana kings, along with several inscriptions dating back to between 70 and 60 BCE. They were commissioned by Queen Naganika, a Maharashtrian princess who married King Satakarani I. These inscriptions give us a first-hand account of life during the reign of her husband and sons.

It is from these inscriptions that we know that the Satavahanas worshipped ancient Vedic gods like Indra, Dharma and Surya, and also some early forms of Vishnu. But they weren’t just patrons of Hinduism. The wealth they collected from tolls was used to build stupas as well. Not only were the first caves of Ajanta carved in their time, but they also built several huge Buddhist stupas in their kingdom, and donated the entrance archway that you can still see at Sanchi.

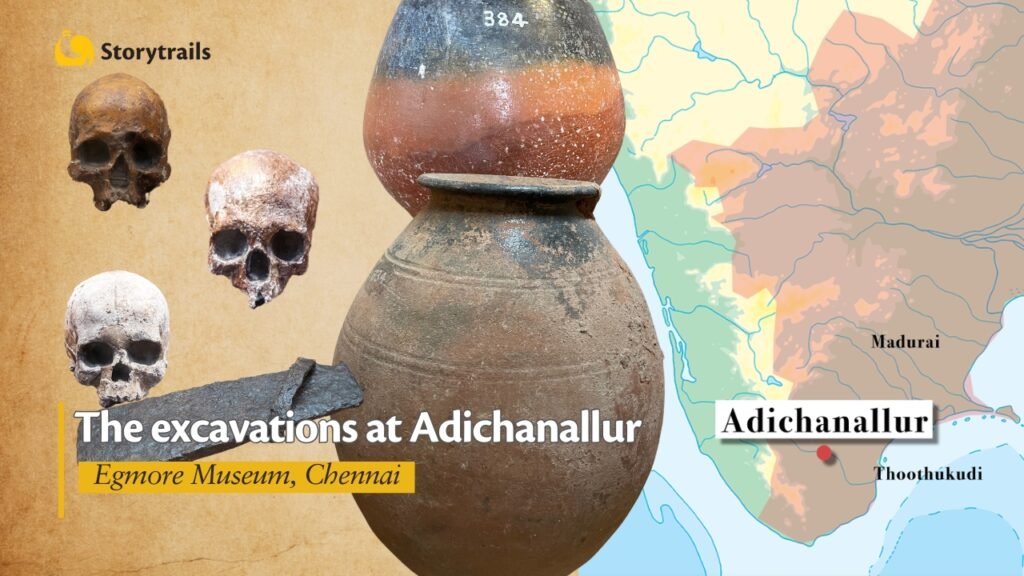

The Satavahanas also built the magnificent Amaravati stupa in modern-day Andhra Pradesh. The Amaravati stupa fell into ruin, and was lost for a considerable period of time. But then the site was rediscovered in the late 18th century, and huge excavation and preservation projects were undertaken.

Today they are the largest collection of both Satavahana and early Buddhist sculptures. This collection is exhibited at the Government Museum in Chennai.

Detour: This short video tells the story of the Buddhist relics of Amaravati:

The Buddhist relics of Amaravati | Egmore Museum, Chennai