The story begins in the early 20th century, when the Indian freedom movement was on the rise. The British government, under Viceroy Curzon attempted to suppress it through force, and then to try and divide the movement through policies such as the partition of Bengal, which divided the province along sectarian lines. This policy failed miserably, the anti-British feeling only grew stronger, and resulted in the Swadeshi Movement – a mass upsurge against British rule.

The British government was forced to make some concessions to Indian demands, and to rethink their strategy. One way was to acknowledge the need to include Indians in the process of governance, through measures such as the Morley-Minto reforms. Formally known as the Councils Act of 1909, this legislation enabled the inclusion of some elected Indian members in the central and provincial legislative councils.

In 1910, a newly appointed Viceroy, Charles Hardinge, was minded to take the process further. He, in consultation with a few close associates in the government, recommended the modification of the very unpopular partition of Bengal, and the elevation of Bengal to the status of a full-fledged province. An important consequence of this step was the need to move the seat of the central government out of Bengal, in order to give the new province suitable breathing room.

The need to locate the capital in a place which was away from provincial capitals like Calcutta, Bombay or Madras was, however, not the only rationale for a new capital for the British in India. Symbolism was equally important. Hardinge wanted no less than a complete image makeover for the Raj. He wanted the Indian people to feel that British rule was for the benefit of Indians, and the British empire was in the long line of Indian empires. For this reason, Delhi, which had been the capital of important imperial powers for several centuries under Mughal and Sultanate rule, was seen as a fit site for the new capital. Thus it was that the British monarch, George V, used the occasion of the Durbar held in Delhi in late 1911 to celebrate his coronation as Emperor of India, to announce the transfer of capital to Delhi.

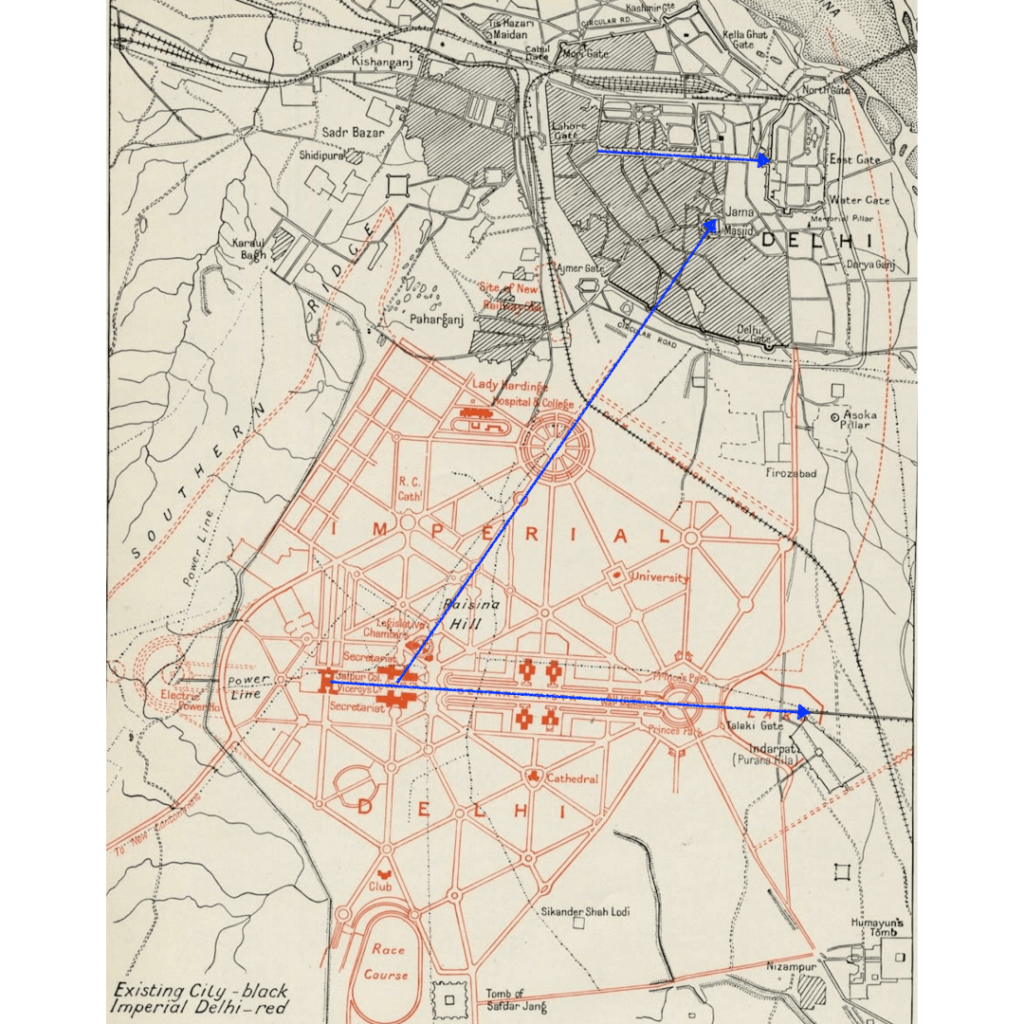

The government shifted to Delhi in late 1912, into a temporary capital, while work began on the new city, which would eventually be called New Delhi. In Delhi the site chosen was the commanding one of Raisina, which overlooked important historic cities of Delhi. These historic landmarks were moreover linked to the new city’s plan in significant ways. The main ceremonial avenue of New Delhi was aligned to the 16th century fortress known as Purana Qila, which was believed in popular tradition to be the site of Indraprastha, the capital of the Pandavas – the epic heroes of the Mahabharatha. This ceremonial avenue, which we today know as Rajpath, was also made exactly parallel to Chandni Chowk, the main ceremonial avenue of the 17thcentury Mughal city of Shahjahanabad, which we now popularly call Old Delhi. Another important road and line of sight linked the Secretariat buildings to the Jama Masjid, the congregational mosque of Shahjahanabad. It was in fact the triangle made by these two major axes that was the foundation of the town plan of Delhi that eventually took shape – based on a complex mix of triangles and hexagons.

The architecture that was to dominate the new capital was the subject of serious and high powered debate. George V had said while laying the foundation stones of the new city during the Coronation Durbar, that the architecture should be worthy of the historic imperial cities of Delhi. The government appointed two well known architects to design the important government buildings – Herbert Baker for the Secretariats and Parliament House, and Edwin Lutyens for India Gate, the Records Office and the Viceroy’s House.

Both Baker and Lutyens were trained in the Western tradition, and their idea of a suitable imperial architectural style lay in the classical traditions of Greece and Rome. Hardinge on the other hand, and George V, were equally adamant that what was needed in Delhi was an emphatically Indian aesthetic. How else would Indians believe in the sincerity of this new Raj in representing their interests and sentiments?

For Hardinge, the answer lay in educating the architects, through reading of works on Indian architecture, and through consultations with architects who had more experience with India. Finally, they had to familiarize themselves with examples of great Indian architecture through personal visits. Given their limited time, these travels only included some sites in North and Central India, though their readings and studies must have been more extensive. The result was a familiarization with some features and examples of Indian architecture, but not necessarily an automatic acceptance of them. While Baker was more tactful, and willing to see the importance of blending the best elements of the East and the West in the architecture of the new capital, Lutyens was outspoken in his disdain for Indian architecture.

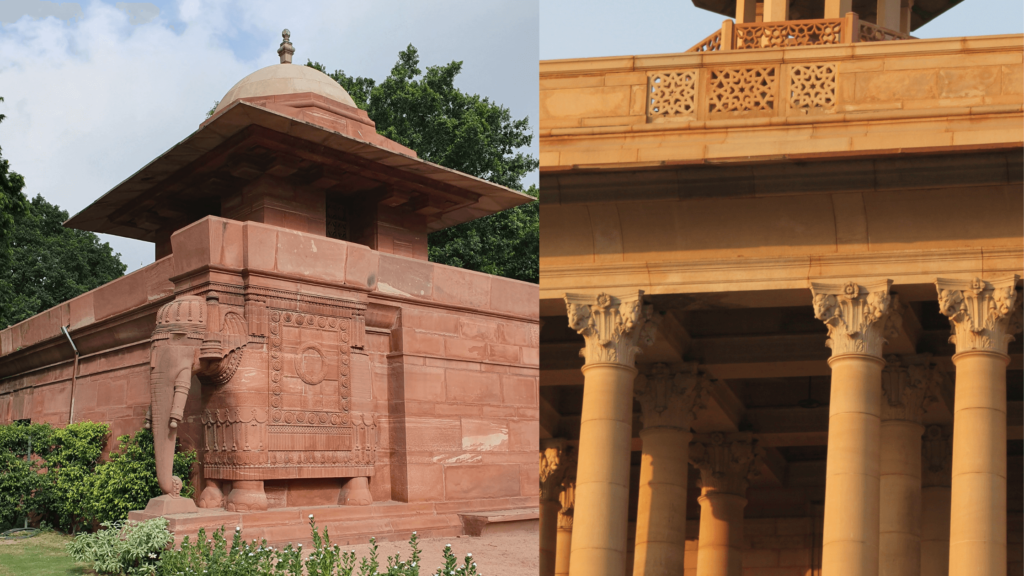

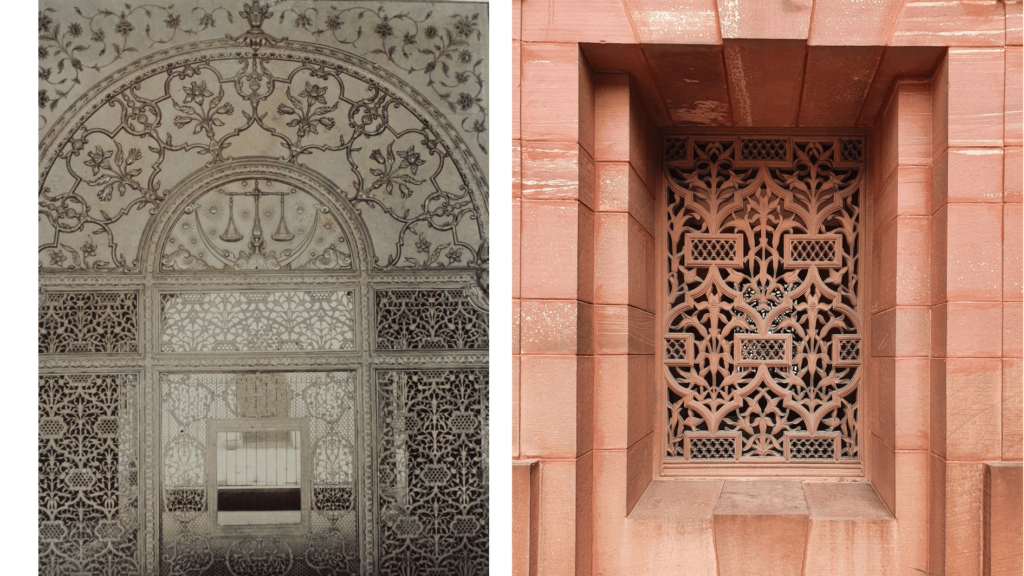

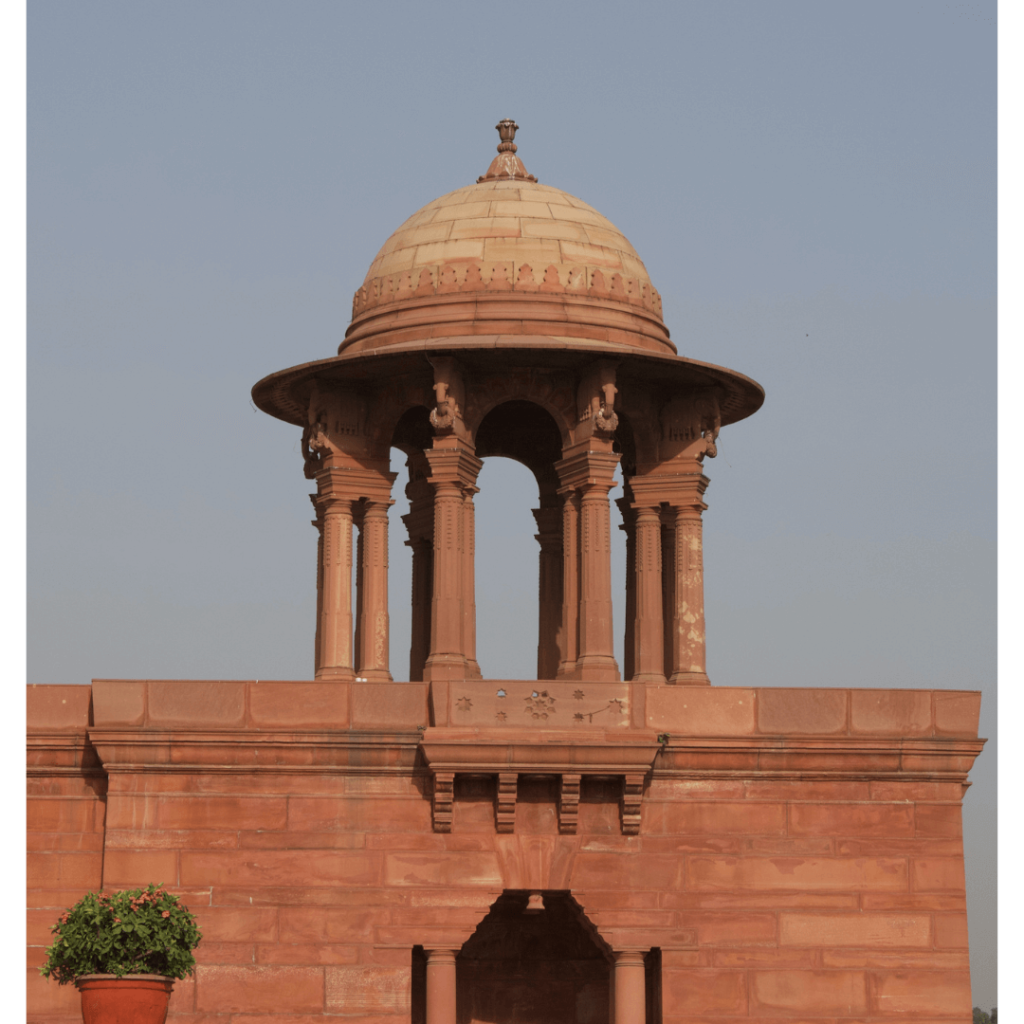

That ultimately both did adapt from Indian architecture is to the entire credit of Hardinge, who resolutely insisted on it. And thus was born the very distinctive architecture we see on Raisina Hill. The red and beige sandstone is the same stone used in monumental Mughal and Sultanate architecture. The chhajjas (projecting cornices) and chhatris (cupolas) are age-old features of Indian architecture, as are the jaalis (lattice work), some of which Lutyens patterned closely on Mughal models. And when in doubt, one could always use elephants – the ultimate cliché in Indianness!

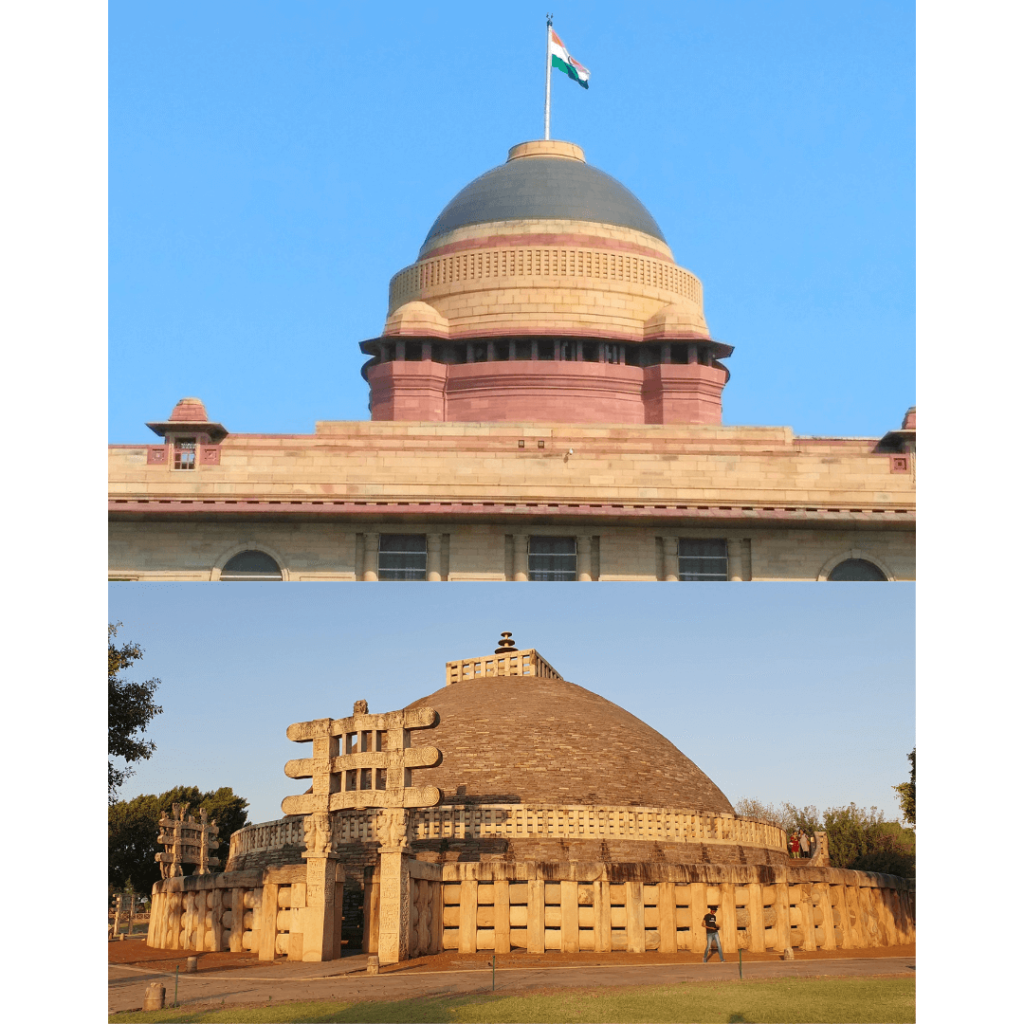

Lutyens, who had expressed many doubts about the Indian architectural tradition, ended up modelling the most prominent feature, the dome of Viceroy’s House (which was completed in 1929, and which we now call Rashtrapati Bhavan), on an icon of ancient India – the Great Stupa of Sanchi.

Dr. Swapna Liddle is a historian and conservationist who specialises in the history of Delhi. She is actively involved in the preservation of heritage sites and works closely with Indian National Trust For Art And Cultural Heritage (INTACH). She has written several books popularising history, including Delhi -14 Historic Walks and Chandni Chowk: The Mughal city of Old Delhi. Her latest book is Connaught Place : The Making of New Delhi.