Suddenly the Tamil word ‘Sengol’ has almost become an un-parliamentary word in some quarters! Most Tamilians know what it stands for. Sengol is a compound word derived from the phrase Semmaiyaana-Kol or the ‘baton of perfection’. It was an ornamental baton held by a ruler or leader to remind them (and their subjects too) that they wielded power only to deliver perfect justice. There is historic and literary evidence for Sengol symbolism that goes as far back as the Sangam era (roughly 300 BCE to 300 CE). The classic Tamil text Tirukkural (which is probably dated around the 1st century BCE ) has 10 couplets dedicated to the qualities of the Sengol holder. One couplet says that, just as all the creatures look up to the sky for rains, citizens look up to the Sengol-wielding king for justice. Sangam literary works like Aganaanuru, Puranaanuru, Iynkurunuru, Kalithogai, Kurunthogai and many more use the word in this sense. These works praise many Chera, Chola and Pandya kings – the royal triumvirate of Tamil Nadu – who remained true to the responsibilities of a Sengol holder. Another couplet of the Tirukkural says that the true power of the king comes not from the spear but from the radiance of the upright Sengol!

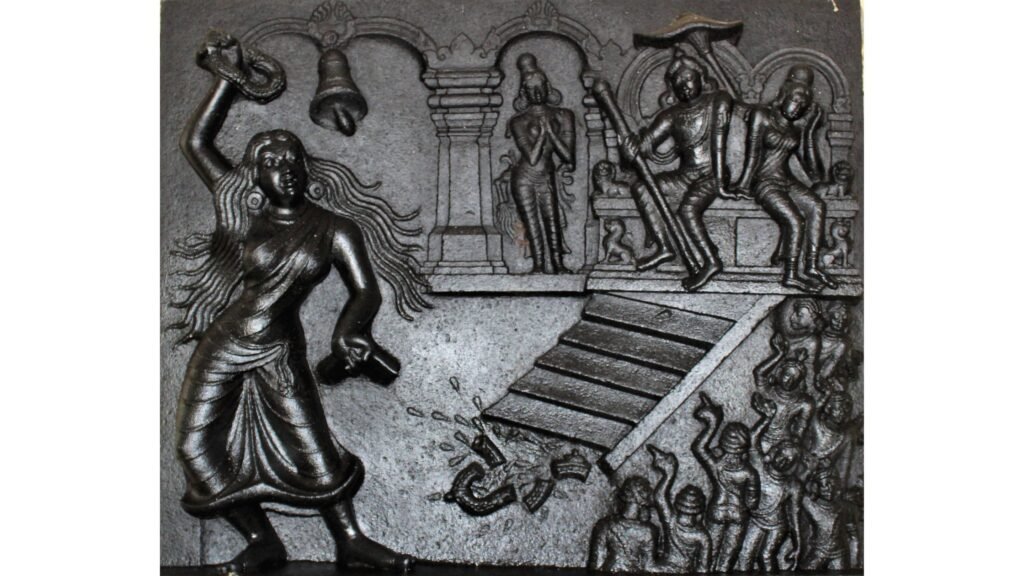

But then, some Sengol holders were not up to the exacting standards demanded by the Sengol. The Silappadikaram, a masterly 5730-line epic composed around the 6th century CE, talks of one such king. The king of the Pandya dynasty Nedunchezhiyan I was a fair ruler until the anklet of his wife, Queen Kopperum Devi, was stolen one day.

The king and queen were disturbed that the crime had happened right under their noses in their palace in Madurai. Kopperum Devi had a dream in which the Sengol of the king slipped from his hands and landed on the ground – an evil omen. The culprit was the royal goldsmith himself but he falsely accused a migrant merchant named Kovalan of the crime in a cover-up. In a moment of weakness, Nedunchezhiyan executed Kovalan, without questioning or analysing the defective evidence of the goldsmith.

Nedunchezhiyan was happy that he had delivered instant justice, but then, Kovalan’s wife, Kannagi, stormed into the court with irrefutable evidence that he had, in fact, executed an innocent man. When King Nedunchezhiyan realised his blunder, the Sengol dropped from his hand, just as the queen’s dream had prophesied. And he cried, ‘I am not the king, I am the criminal.’ The shock that he had failed the Sengol was so much that he died instantaneously. Such was the power of the Sengol.

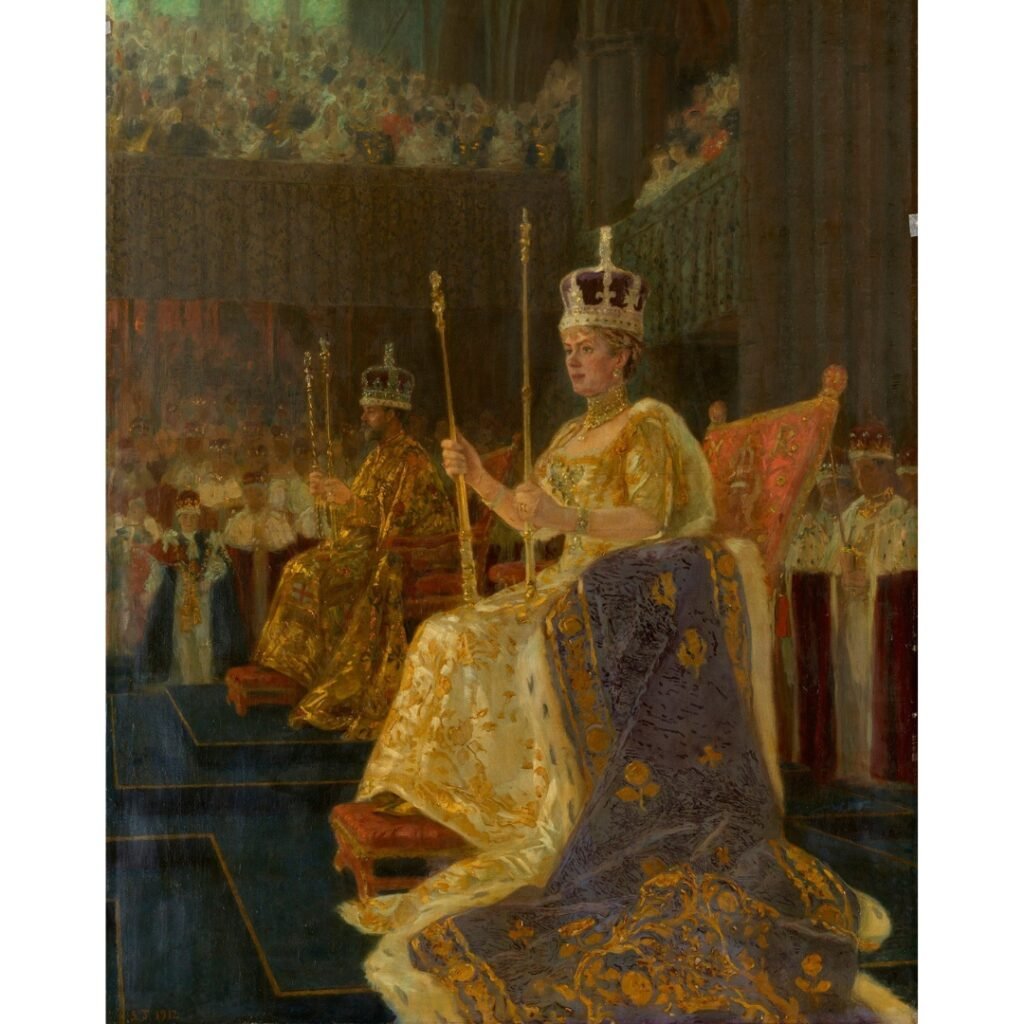

The British have the equivalent of the Sengol in their sceptre. A sceptre has the same function as the Sengol: to serve as a symbol of royal power to deliver absolute justice. Recently, King Charles was crowned as the king of the United Kingdom. The ceremonial paraphernalia included the sceptre, which, according to them, is their symbol of justice. The press, especially the South African press, begged to differ. This sceptre was studded with a large diamond called the Cullinan I.

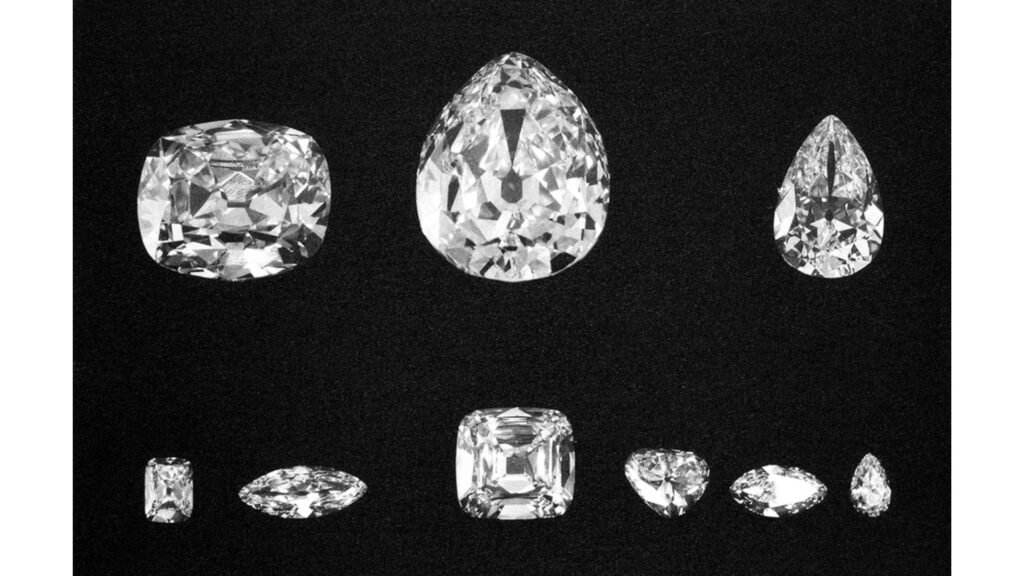

The original Cullinan diamond was one of the largest diamonds in history. It was mined from the Cullinan mines in South Africa. It was so large that there were no buyers for it for two years. The government of Transvaal (a Dutch South African colony which became British after the Boer War) made a deal with Cullinan and bought the diamond. They later gifted it to King Edward VII of England. It was Transvaal’s way of showing that it had aligned with its new colonial master.

This diamond was cut into nine pieces, and the biggest piece (named Cullinan I) was affixed on the royal sceptre. The press claimed that the sceptre was tainted. It was looted from the African colony after exploiting black labour to mine it. It was a blood diamond, pure and simple! The British government maintained that it was a gift from South Africa.

What did Queen Camilla wear on the occasion? She would have worn the state crown which had the Kohinoor diamond on it. The Kohinoor is said to be cursed, bringing bad luck to the wearer, unless the wearer was female. So, it has been a tradition that only the queen wore it on ceremonial occasions like this. We do not know if Queen Camilla worried about the curse, but for the coronation ceremony, the Kohinoor in the crown was replaced by another diamond. The Kohinoor has already created bad blood between India and the UK. (The UK government maintains that it was a ‘gift’ from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s son, while the Indian government has maintained that he was pressured into parting with it.)

Ironically, the diamond that replaced the Kohinoor in Camilla’s crown was tainted too: it was Cullinan II, which was another piece from the original raw Cullinan diamond!

Detour: Watch this short video for the story of the Kohinoor.

There is one more controversial Sengol-sceptre story. At the coronation, Queen Camilla also carried a sceptre that has been ceremonially used since the coronation of King James II in 1685. This three-feet sceptre is made of ivory, which has riled up animal rights activists. But the crown refused to change its tradition and even suggested that it supported conservation. And support came from an unexpected quarter – South Africa. One South African leader said, ‘Even our own chiefs use ivory and other animal parts such as tails and skins as symbols of the greatness and richness of African culture and their role in preserving it.’

William Shakespeare had his own take on the Sengol. Here is a soliloquy by Henry V from the play of the same name:

‘Tis not the balm, the sceptre, and the ball,

The sword, the mace, the crown imperial,

The intertissued robe of gold and pearl,

The farcèd title running ‘fore the king,

The throne he sits on, nor the tide of pomp

That beats upon the high shore of this world—

No, not all these, thrice-gorgeous ceremony,

Not all these, laid in bed majestical,

Can sleep so soundly as the wretched slave

Who with a body filled and vacant mind

Gets him to rest, crammed with distressful bread…

As the sceptre holder, King Henry carries the sole responsibility of doing the right thing for the country. Such extreme power brings so much pressure that a ‘wretched’ slave – who has no such responsibility – appears far happier. Such is the isolation of the Sengol-sceptre holder… well, at least according to Shakespeare.