There was a time when Indian temples acted as bankers for the communities they were a part of. Isn’t that rather strange? Well, apparently not to our ancestors. In today’s world, we perhaps see religion and personal wealth as two different silos. But back then, all human activity was seen as a part of a single continuum, which included both faith and finances.

Today, it is hard to imagine temples doing commercial lending, because most of them are at a subsistence level. But it wasn’t always like that. Many ancient temples had enormous reserves, and a few of them continue to do so. For instance, the Tirupati Balaji Temple in Andhra Pradesh was considered to be the richest temple until recently. Its wealth is estimated at roughly Rs 2.3 trillion (about USD 28 billion). Then around the year 2011, the courts ordered an investigation into the vaults of the Anantha Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. The result was an amazing revelation: the temple’s net worth is over Rs 3 trillion (over USD 38 billion), easily surpassing the Tirupati Temple! These are not small amounts. In fact, they are greater than the GDP of many small countries! And surely, one can run a few banks with this kind of capital.

Detour: Watch our video on the Padmanabhaswamy Temple to know more about it.

How did these temples come into so much wealth? Typically, Indian kings and aristocrats patronised temples. In fact, kings spent a large part of their treasury building temples. Naturally, the mightier the kings, the grander the temples! The simplest explanation is that the kings considered it good karma to build shrines. And karma was not necessarily restricted to Hindu temples. The early Buddhist shrines at Ajanta were commissioned by the Hindu Satavahana kings, and the Chudamani Vihara Buddhist Shrine in Nagapattinam was patronised by the Imperial Cholas. Temple sponsorship was brand-building for any king; after all, he was the defender of the faith in his country, and people, somehow, trusted a more religious ruler. Moreover, temples also served as cultural and education centres. And, of course, large public projects like temples spurred high levels of commercial activity, which was good for the economy.

Usually, the kings’ descendants continued patronising the temples, because tradition was important. And the wealth-building persisted. But what would happen if another king invaded the country? Often, the invader would be a Hindu king with the same motivations. So, in the process of consolidating his new conquest quickly, he would often patronise the same temples. Around 730 CE, Chalukya king Vikramaditya II ravaged the Pallava capital of Kanchipuram. It was a revenge attack on the Pallavas and looting of enemy temples was on the agenda. But when he saw the beautiful Kailasanatha Temple, he changed his mind. Instead of looting it, he ended up making donations to it! And we know this from the Kannada inscriptions commissioned by Vikramaditya himself.

Such wealth was carefully assembled over the rule of many lines of kings and the Padmanabhaswamy Temple is an excellent example of this kind of accumulation. For centuries, Kerala had been the centre of international spice trade and much of the profits found its way into this temple. The ruling Cheras, as well as rival Tamil kings like the Pandyas, Pallavas and Cholas donated large sums of money to the temple. When there was political instability in Kerala during the 17th and 19th centuries, some feudatory kings sought refuge in the Travancore kingdom. And they too made grateful donations. All this wealth was carefully preserved by the Travancore kings who considered themselves Padmanabha Dasa, or “servants of God”. The stories of other temples were similar, though less dramatic.

Yet, there was always a risk of a descendant or an invader destroying the accumulated wealth. This risk could be eliminated by delinking the temple’s finances from the royal treasury. And the clever kings of the Chola dynasty did exactly that. They made donations which would be held in trust, and reinvested. The return from these investments would then finance the temple maintenance in perpetuity, therefore, ensuring its safety. Once this cycle was established, it no longer needed royal support; the temple was well and truly independent of the king.

Detour: Listen to our podcast on the story of the Brihadeeswara Temple, Raja Raja Chola’s magnum opus

The temple played by its own rules, managing its own investments and funding its own activities. Today, if you were a not-for-profit charity, where would you invest your reserves? Most probably, in government bonds, AAA-rated securities and fixed deposits, but never in speculative grade instruments. The investments of the Tirupati Temple are a case in point. In its investment portfolio, it has about Rs 160 billion in fixed deposits in scheduled banks.

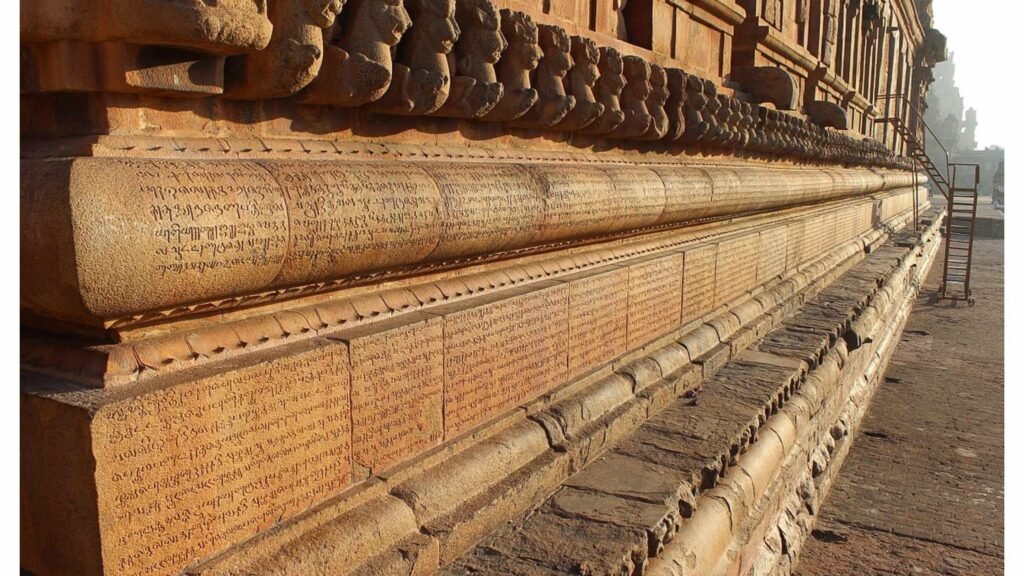

About a 1000 years ago, Chola temples did something similar. Royal inscriptions on the walls of the Brihadeeswara temple at Thanjavur give a detailed account of its assets: bronze icons, jewellery, farmlands and real estate; and they had hard cash too. One inscription, which we shall informally call the “Banana” inscription, gives an insight into how they invested in cash.

According to the inscription, Raja Raja Chola was informed that the Lord Ganesha shrine inside the Brihadeeswara Temple needed 150 bananas every day, for rituals and distribution to devotees. Now, let’s do some quick maths. That would make 54,000 bananas per lunar year of 360 days, or an expense of 45 Gold Kasu at the prevailing market rate. (A Kasu was a lot of money those days.) The sharp king reckoned that at the ruling interest rate of 12.5%, a fund of 360 Kasu would earn an interest of 45 Kasu per annum. And promptly, he donated 360 Kasu to the temple.

Now, here comes the banking connection. Unlike the modern Tirupati Temple, the old temple had no options like government bonds or fixed deposits in scheduled banks. But there was an option of lending to large corporates – yes, they existed back then too! In Chola times, these were the merchant guilds, some of which were MNC equivalents with huge operations in the Far East. The “Banana” inscription says that the temple lent the 360 Kasu at 12.5% to four specific guilds, which probably had some royal accreditation. The amounts lent to each guild was different, presumably based on their credit rating. By lending to four different guilds, they had also diversified their credit risk over four borrowers, like any good banker should!

What we can infer from the “Banana” inscriptions is this: temples had the means, opportunity and capacity required to succeed in the banking business. But here’s where they differed from our modern banks; their objective was not endless profit maximisation. Rather, the generation of surplus was for maintaining their traditional service. After all, they couldn’t forget their duties to God.