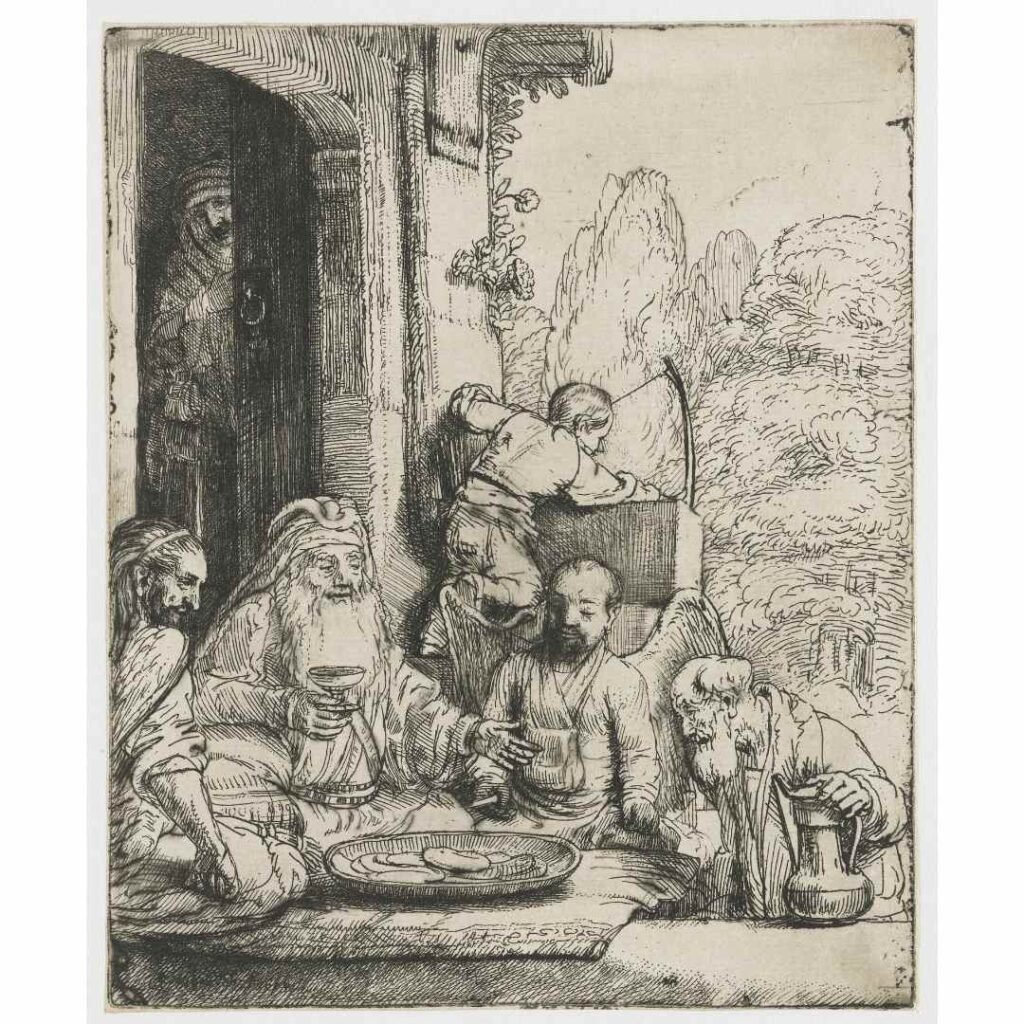

Even if you know nothing else about him, you’ve probably heard the name ‘Rembrandt’ at some point in your life. You might have even seen one of his famous paintings: maybe The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, where a group of men lean over a cadaver as a doctor reveals what a hand looks like without skin, or maybe the dashing company of swordsmen featured in the sprawling canvas of The Night Watch. Rembrandt is considered one of the masters of the Dutch Golden Age of painting, a period which roughly spanned the length of the 1600s. Even in his lifetime, he was renowned as one of the foremost exponents of etching, which involves working fine detail into a metal plate which was then used to make prints through a printing press. Rembrandt was also an avid art collector, and artworks from all over the world found its way into his hands.

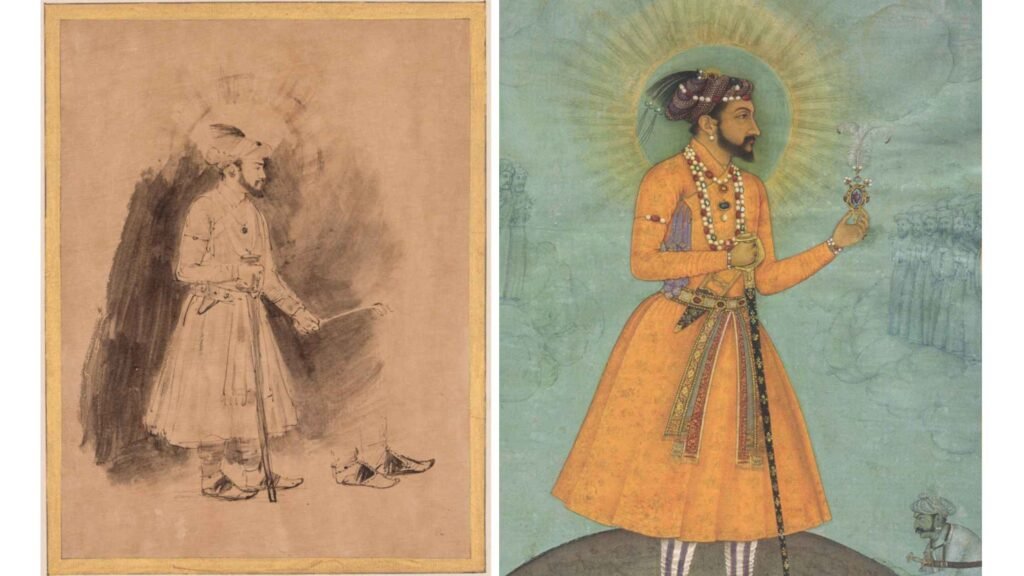

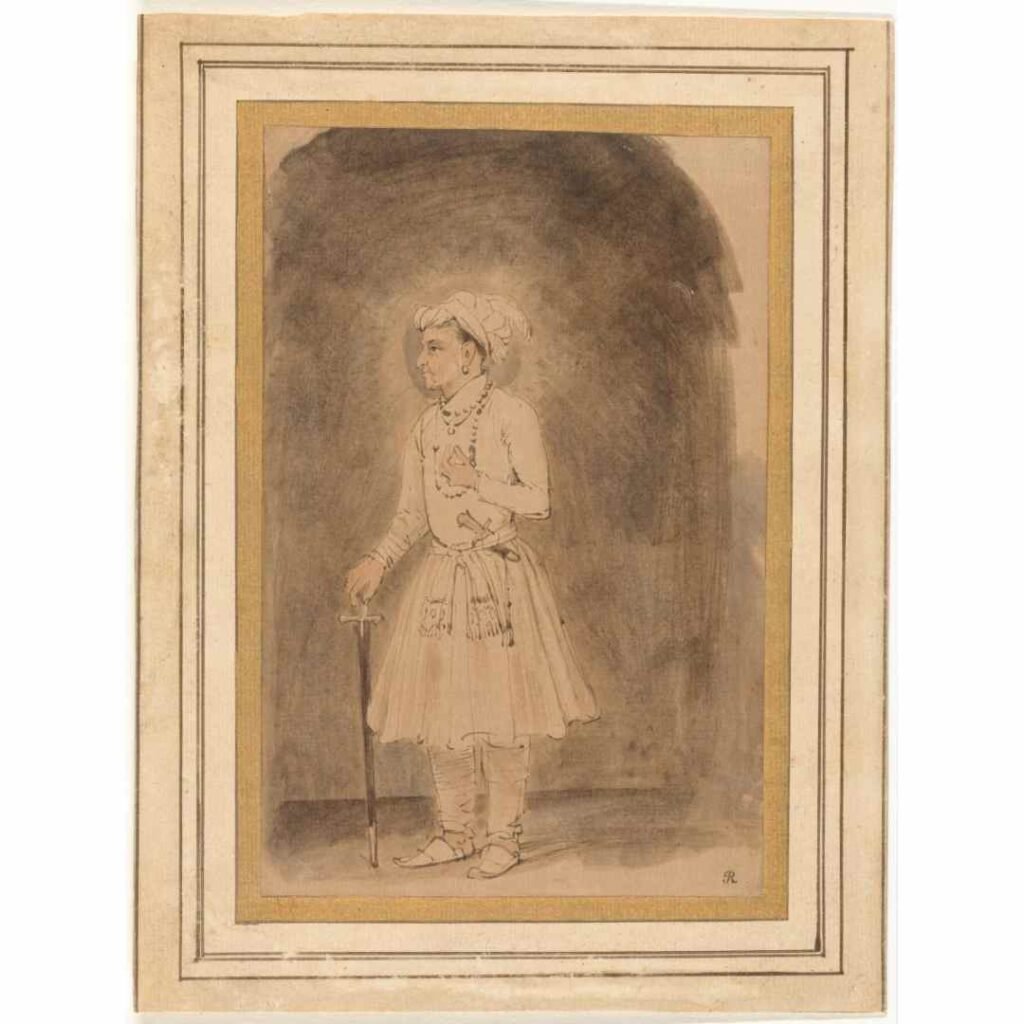

At some point, in the mid-1600s, Rembrandt came across examples of Mughal art and was so inspired by their noble-looking subjects and elaborate costumes, that he began to produce work in that style. Today, we have 23 different pieces by Rembrandt, all in his ‘Mughal style’, dating from a brief five-year period from 1656 to 1661.

But how did Rembrandt even come across Mughal art?

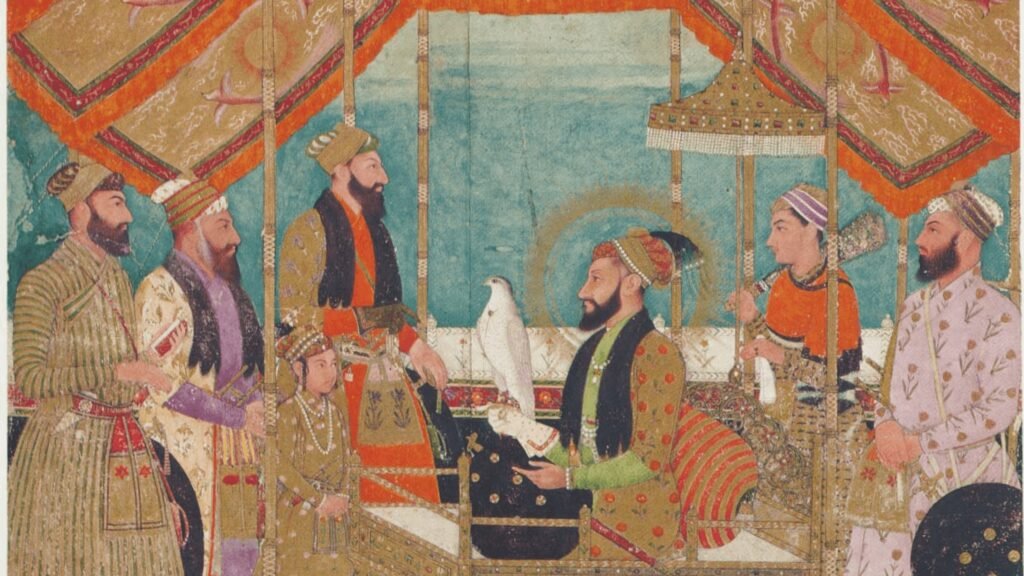

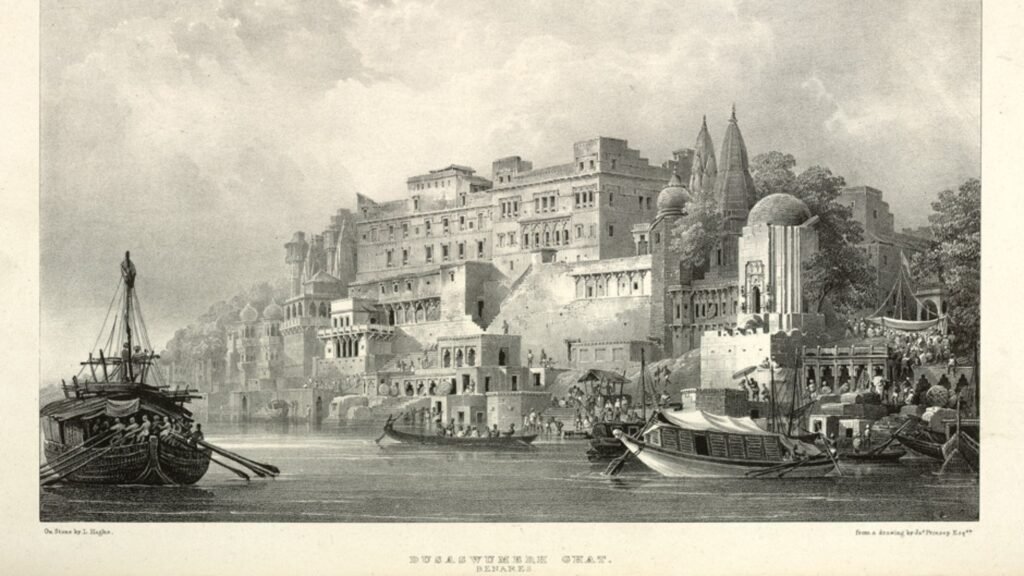

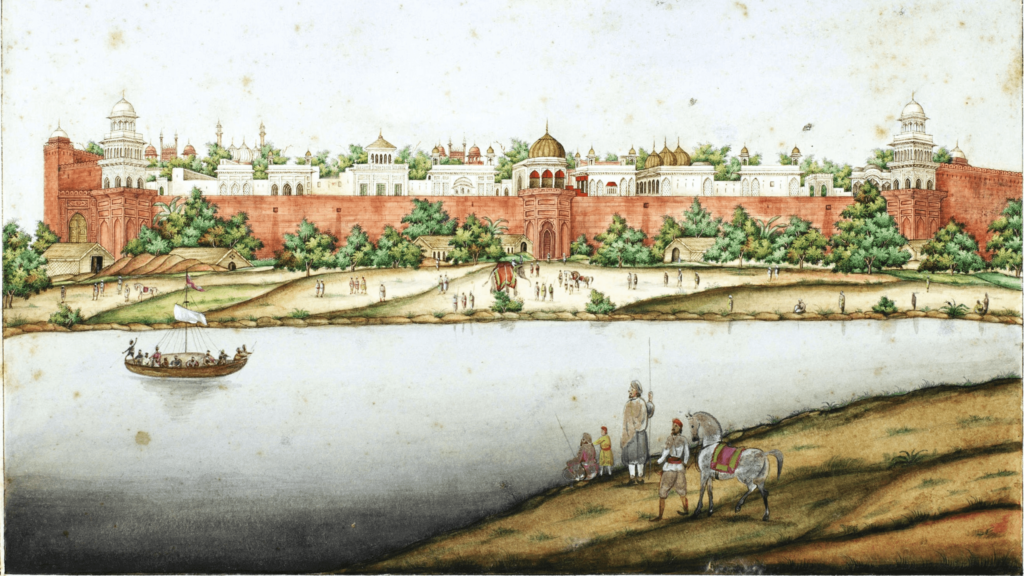

The truth is that Mughal art had probably been coming to Europe for decades by that time. The British had set up a factory in Surat in 1612. The Dutch too set up a trading post soon after, in 1616. At that time, Surat was one of the busiest ports on the western coast of the Mughal Empire, whose capital was in Delhi. The king at that time was Jahangir, a great patron of the arts. His court was full of painters and poets vying with each other to produce the finest works. Soon, a steady stream of artworks began to filter into Europe on trading ships, alongside textiles and spices.

These imported paintings were not commonly available, of course, and Rembrandt doesn’t seem to have actually owned the pieces that inspired his work. But based on close study, scholars feel that some of his inspirations may have been displayed in the Schönbrunn Palace in Austria. Others seemed to have come from albums known as muraqqa, which were books of paintings, prints and drawings that had been stitched together.

While he avoided bright colours for simpler line work, it’s clear that Rembrandt took great care in his reproductions. These weren’t practice sketches. They were drawn on rare Japanese paper that the Dutch East India Company brought to Europe. His attention to detail is obvious, especially with regard to facial expressions and costume. In one portrait, he takes great pains to depict Shah Jahan with a white beard. Story goes that after his beloved wife’s death, Shah Jahan’s luxurious black beard beard turned a snowy white. The folds of turbans, the fall of sashes, the design of jewellery and shoes – every little detail was painted with care. One curator points out that Rembrandt, unlike some other artists, did not cast these “exotic” people and objects into fantastical settings. Rather, he earnestly copied them, as he would have copied the works of other European masters – as a way of learning.

But, as art historian Yael Rice eloquently explains, Rembrandt shouldn’t be seen as some cross-cultural hero but as one member in a much larger conversation. European prints and paintings had been circulating in India even before Rembrandt was born. Mughal painters copied and learned from them as well. Some even painted over European prints, using them as outlines in the way a colourist in a comic book today might use the sketches of the illustrator. It’s important to remember that even in the 17th century, the world wasn’t a very big place!