The true story of the king of Gingee Fort is very different from the romantic tale in folk performances.

In 1960, a Tamil fiction film called Raja Desingu was released, starring the swashbuckling matinee idol, MGR. It flopped. But Raja Desingu’s story continues to be told in street performances like Therukoothu, Poi-Kal-Kuthirai, and even the Burra-Katha tradition of Andhra. In fact, many boys in Tamil Nadu are named Desingu even today, after the legendary hero of Gingee Fort in Tamil Nadu.

So who was Desingu?

There is a popular folklore version of the story, often seen in street performances. And there are historical accounts that tell a different story.

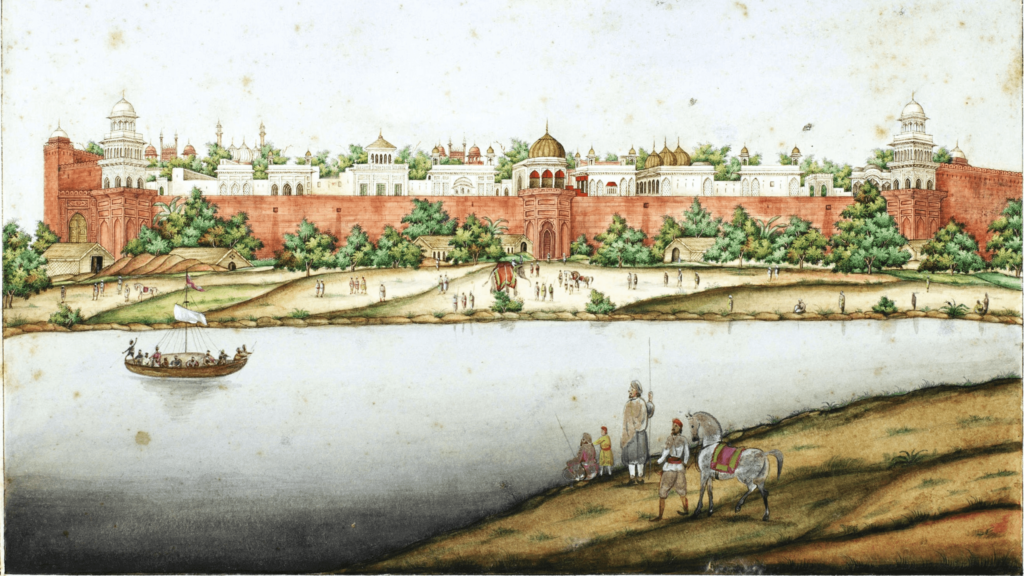

Here’s the folklore version. Raja Desingu’s father was a commander in the Mughal army. In return for his loyal and brave service, the emperor gifted him the territory of Gingee, absolutely tax free. He ruled from the fort for many years. When he died, Desingu lawfully inherited the territory. That’s when he ran into problems with the Nawab of Arcot, who was regional Governor of the Mughals. The Nawab wanted Desingu to pay the regular tributes because the emperor’s gift was not ‘inheritable’. Desingu cried foul – he had inherited Gingee, fair and square. But the Nawab declared war.

Desingu Raja was loved by his subjects because he was noble and brave. And to add a romantic touch, he was newly married. Maavuthukaran, another feudatory, was his ally and best friend. If you thought Maavuthukaran was a strange name, it is the Tamilised form of Mahabat Khan. Maavuthukaran sounds more musical in a ballad than Mahabat Khan, so, well, poetic licence! The Nawab attacked the Gingee Fort with 80,000 men; Desingu had less than 800 soldiers in the fort. Is it true that the Nawab actually sent 80,000 men after 800 men? Not really. That’s poetic licence at work again. This was awkward for Desingu, because Mahabat Khan had gone on leave to get married. Fortunately, Mahabat Khan got the news of the impending attack just before tying the knot. Desingu needed him more than his fiancée now. He told her he would be back in a moment, put on his armour, and rode into battle!

Meanwhile, Desingu went to the Ranganatha temple to pray for victory. Alas, Lord Ranganatha turned the other way (indeed, you can see this deity with his head positioned in an unusual angle even today). An ominous sign, but Desingu rode into battle anyway, with Mahabat Khan joining him. The numbers were against them. Mahabat was killed right in front of Desingu’s eyes. And before Desingu could grieve for him, his own horse was killed. Desingu continued to fight on foot but was killed eventually. Desingu’s wife committed sati by jumping into his funeral pyre. Death elevated Desingu instantaneously to a cult hero: a local lad who died fighting marauding invaders!

Folklore has a way of romanticising grim, boring truths sometimes. There are many sources of recorded history – the records of the Marathas, the Nawab and the colonial Europeans. And each one offers a slightly different version of the truth. Here is a more neutral reconstruction after reconciling all the versions.

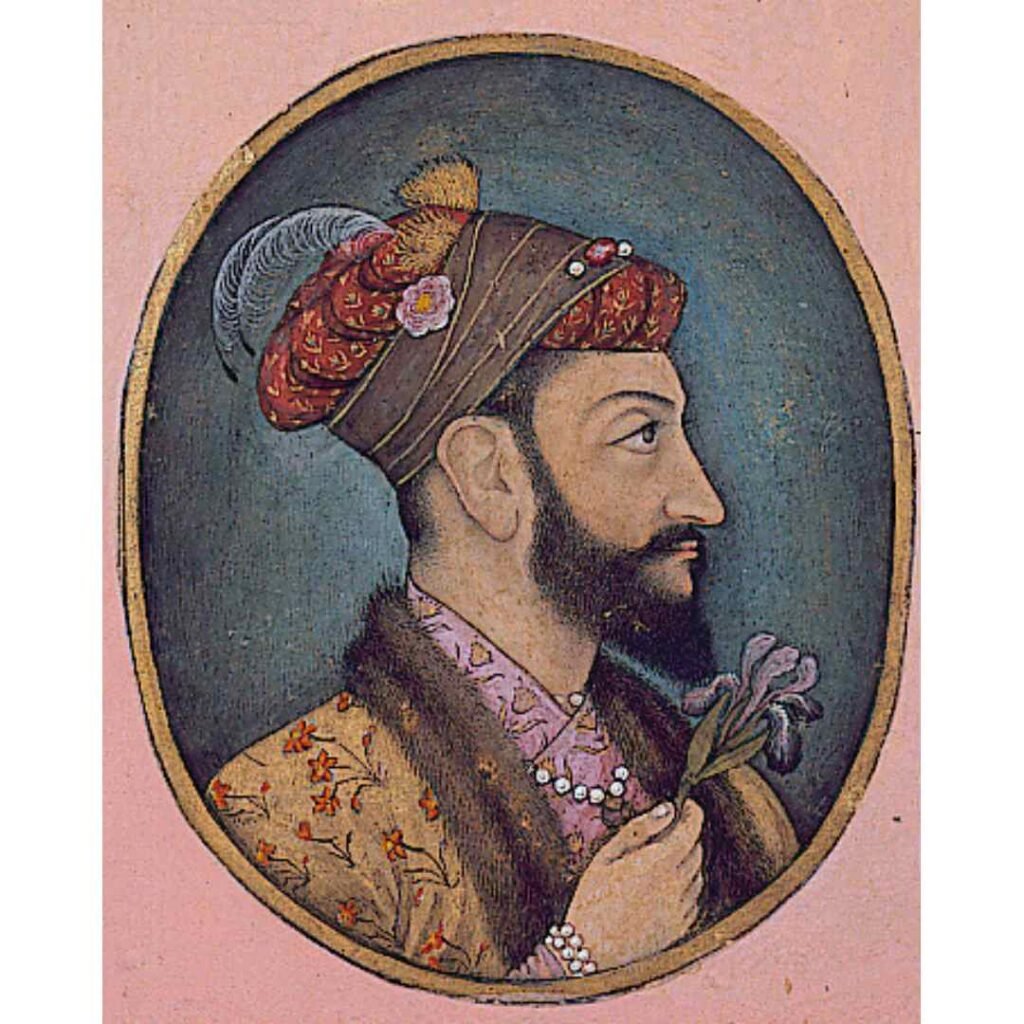

First things first, Desingu was not a local lad: he was a Rajput named Tej Singh. Of course, the name got Tamilised as Desingu in the ballad – more poetic licence. His father was a Rajput commander named Raja Swarup Singh Bundela under the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. For his role in courageously defending Mughal territory against the Marathas, Aurangzeb was pleased to make him a Mansabdar and Qiladari of Gingee Fort…essentially, a feudatory chief with a fort. It was an imperial reward, so Swarup Singh enjoyed a tribute-free autonomous rule of Gingee. Aurangzeb died in 1707, but Swarup Singh continued as the Gingee overlord till his death in 1714. His son Tej Singh (aka Desingu) ‘inherited’ the territory of Gingee. This ‘inheritance’ became a moot point.

The Nawab had two issues with it. Firstly, Tej Singh was not entitled to automatically inherit his father’s post. Even if he did want to rule over Gingee, he needed to pay tributes to the Mughal government, with arrears. And that amounted to a whopping 7 million rupees! The Mughal Empire was a humongous bureaucracy. Southern India was managed by the Mughal Viceroy, the Nizam of Hyderabad, Asaf Jah, and he in turn had local governors; Gingee came under the Nawab of Arcot, Saadatullah Khan. These functionaries were largely autonomous, but when it came to collection of revenue from the feudatories, rules were rules. Tej Singh stubbornly maintained that he had inherited the gift from Emperor Aurangzeb and no tributes were due. Aurangzeb was dead and unavailable for comment, while his successor Bahadur Shah I couldn’t be bothered by ‘petty’ disputes. So, like all tax notices, the Nawab’s demand notice was virtually unchallengeable.

From here, history is a tad unclear. The Maratha records paint a picture that the ‘evil’ Saadatullah attacked the ‘innocent’ Tej Singh. Naturally, that’s because the Marathas hated the Mughals. The Nawab’s records suggest that he was patient with Tej Singh and that he had tried his best to explain the rules; it was the cocky young Tej Singh who wanted war. Saadatullah never wanted to kill Tej Singh; in fact, in the battle, Tej Singh was captured alive. It was only when he tried to escape by killing his escort that he was killed. And apparently Saadatullah ‘permitted and facilitated’ Mrs Tej Singh’s sati so that she could die honourably. He was so impressed by his opponents’ bravery that he even built cenotaphs for Desingu and his rani near Arcot at Ranipet (so named in honour of the rani who committed sati).

Over the centuries, the myth has pervaded over the material facts. Figuratively speaking, Gingee Fort quietly sits on a mountain that was once a mole-hill!

The fort is now a protected monument and can be covered in a day trip from Chennai.