Murder most foul

In 971 CE, a popular prince was assassinated in broad daylight. He was Crown Prince Aditya Chola-II, who was already the co-regent of the mighty Chola kingdom at Thanjavur. Who was behind the murder, and why? This question has intrigued historians and writers for over a thousand years. In the 1950s, Tamil novelist and journalist Kalki Krishnamurthy wrote a 2200-page whodunit bestseller around this, called Ponniyin Selvan. Kalki’s work was fiction, but it was based on painstaking research of Tamil history. It was filled with actual historical events, told not from a Western perspective, but an Indian one. This stirred public interest in local history.

Here is the real story that made Kalki’s version so exciting.

Who were the Cholas?

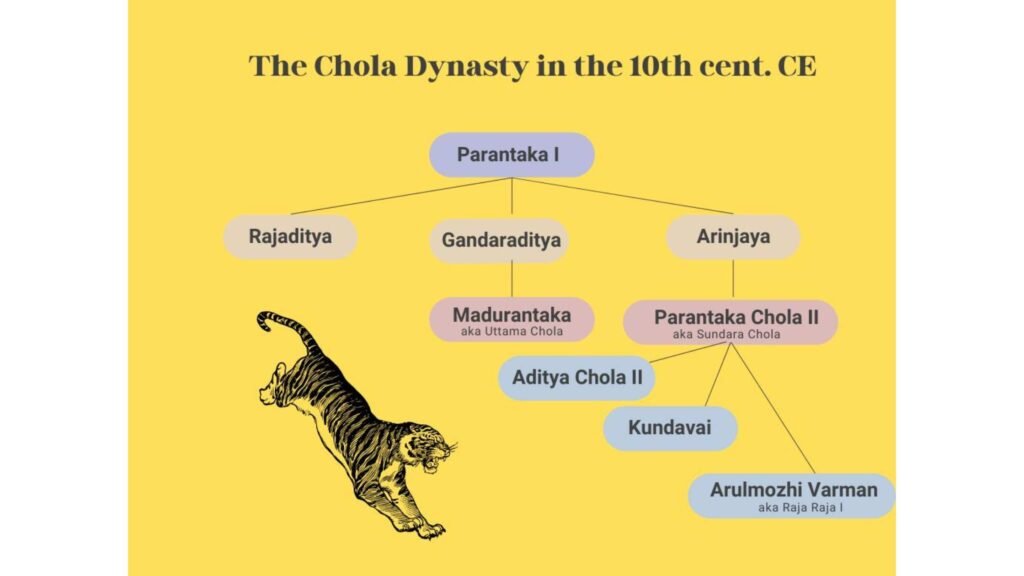

The Cholas were a powerful dynasty that ruled in south India for over 1500 years. We don’t know who established this dynasty, but there are inscriptions from Ashoka’s time (3rd cent. BCE) that mention the Cholas. Like all dynasties, it had its ups and downs. During the reign of Parantaka Chola I (907-950 CE), the kingdom became a rising power. Unfortunately, his eldest son and heir-apparent, Rajaditya was killed in battle, and the aging Parantaka named his second son, Gandaraditya, as the next ruler. When Gandaraditya died, his son Madurantaka was still an infant, so Gandaraditya’s younger brother Arinjaya ascended the throne. Arinjaya too died within a year, and Arinjaya’s son Parantaka Chola II (aka Sundara Chola) ascended the throne. Madurantaka was still a child, so he was still disqualified from the race for the throne…for now. Usually in the Chola dynasty, it was the eldest son who became king, but Madurantaka had missed his chance twice in rapid succession because he was far too young.

Parantaka II proved to be as ambitious as his grandfather Parantaka I. Under his leadership, the Chola kingdom expanded once again, and his powerful army defeated many of the neighbouring kingdoms. He was supported by his eldest son Crown Prince Aditya II, who was named heir-apparent and co-regent. This probably came as a shock to Madurantaka, because he realised he had missed a shot at the throne for the third time. He was no longer a child and he was not getting any younger either!

Meanwhile Aditya II was proving to be a bold and valiant warrior. At the battle of Chevur, Aditya tackled the Pandya King Veerapandya and killed him in a one-on-one face off. Then in a brash act, he chopped Veerapandya’s head off and held it on a post for everyone to see. He triumphantly returned to Thanjavur as Veerapandyan Thalai Konda Koparakesari Varman Karikalan (‘the great king who beheaded Veerapandya’).

Aditya II was all set to be crowned king, but then disaster struck. In the year 971, the prince was brutally murdered. Before we look for the murderer, let us look at what happened next.

The fallout

Aditya’s younger brother Arulmozhi Varman (also spelt Arunmozhi Varman) was well liked too. And, like we saw, there were precedents for crowning a younger brother when a direct descendant was unavailable. So, now that Aditya II was out of the picture, Arulmozhi was the popular choice for king. Oddly enough, Arulmozhi declined the honour and proposed that his uncle Madurantaka (who, remember, had missed three chances!) was the right choice: he was the eldest in the family and Arulmozhi would be pleased to serve him. Thus, Madurantaka was finally crowned as Uttama Chola. He ruled for nearly 15 years and on his death Arulmozhi ascended the throne as Raja Raja Chola I. The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

Whodunit?

Back to our question: who killed Aditya? Even after 1000+ years, two solid pieces of evidence have survived: the copper plates from the Tiruvalankadu Siva temple and the stone inscriptions at the Udayarkudi Anantheeswara temple. From the inscriptions we gather that the actual conspirators were Soman, Ravidasan and Paramesvaran — three brothers who had been officers in the Pandya/ Chola government. The inscription lines are brief and therefore, one has to carefully apply contextual knowledge to unravel the mystery. Naturally, different scholars have offered different interpretations!

In any murder case, detectives look for three things: motive, opportunity and intent. Historians do the same too. Who would be the prime suspect? Perhaps it was Madurantaka aka Uttama Chola. He had a really strong motive. Thrice he had been denied access to the throne – and the last time it was because of Aditya. Surely he must have felt angry at the turn of events. Besides, was it not Uttama who benefited most from Aditya’s death? He had the opportunity too. He was a royal with resources and access to covert operatives. (If Kalki’s book is an indicator, the palace was full of spies and counter-spies, and Uttama could have used them very effectively.) According to Prof. KA Nilakanta Sastry, a leading authority on Chola history in the 1950s, the shadow of doubt clearly falls on Uttama. He validates his suspicion on the premise that the culprits were never identified during 15 years of Uttama Chola’s rule, but were swiftly discovered and punished within the first two years of Raja Raja’s reign.

Not everyone agrees.

They ask, was Uttama capable of evil intent? Apparently not. Uttama Chola turned out to be an unambitious ruler, known to be a principled and pious person. In fact, Raja Raja (aka Arulmozhi) named his son (the future king Rajendra) Madurantaka, after his uncle. Would he have done that if there was the slightest suspicion that his uncle had murdered his brother?

Raja Raja was also a great favourite of Uttama’s mother (Sembiyan Mahadevi). He continued to treat both Uttama and his mother with great love and respect till the end. The intent factor seems to be completely missing according to later scholars like Kudavayil Balasubramanian.

Then, could Arulmozhi, the great Raja Raja be the sponsor of the murder? He had motive and opportunity. He was popular, and if Aditya was out of the way, he could have become king. Now the problem with this theory is the assumption that the Chola hierarchy operated like the Mughal hierarchy. Often in the Mughal system, all the sons of the deceased king fought fratricidal wars till the lone survivor became the king. The Chola system was not an all-or-nothing game; it had more benign power-sharing, with other sons enjoying powerful positions in the government. There was no need to fight to stay relevant in politics. Raja Raja did not benefit from Aditya’s murder, because he willingly surrendered his imperial claim in favour of his uncle. He realised that a sulking Uttama could create disunity in the Chola family, so it was better to please a senior and await his turn patiently. Mature moderation, not murder, was Raja Raja’s intent.

Many scholars say this was an ‘honour killing’. Aditya had won the battle, but he had heaped indignity on his enemy by publicly parading the slain King Veerapandya’s head. That dishonour had to be avenged by Pandya loyalists, and they hired the three assassins to do the dirty job. This ‘foreign hand’ theory is now considered the most plausible explanation.

And the verdict is… *spoiler alert*

Who was the murderer in Kalki’s novel? Kalki was influenced by the theories of the 1950s, which assumed Uttama was the perpetrator. Kalki left broad hints pointing to Uttama, without actually naming him. He cleverly left the question tantalisingly open to the readers.