In May 1909, the Indian and the British press waited with bated breath for the judgement on the Alipore Conspiracy case. It was a sensational case: not just because it revolved around a high-profile assassination attempt, but also because all of the accused belonged to the Bengali bhadralok (upper-class genteel families)! Two of the key accused were the sons of an Indian doctor, who had stayed in England for a while so that he could educate them to become more British!

The Ghosh Family

Dr Krishnadhan Ghosh was an admirer of the British. He moved to England in 1879, so that his sons could study in England, pass the Indian Civil Service (ICS) exams and join the British elite. His two elder sons did not meet his expectations, and he was forced by circumstances to return to India before his fourth son Barendra (Barin) could be enrolled. It was left to the third son, Aurobindo, to appear for the ICS. Aurobindo was a brilliant student. He passed the preliminary tests with ease. But while training at Cambridge University, he began to despise British imperialism. He deliberately got himself disqualified in the riding test and sabotaged his own ICS career. And he sailed to India in 1893. Meanwhile, Dr Krishnadhan was misinformed by the travel agent that Aurobindo’s ship had sunk, and the doctor died of shock. Aurobindo returned to a gloomy India.

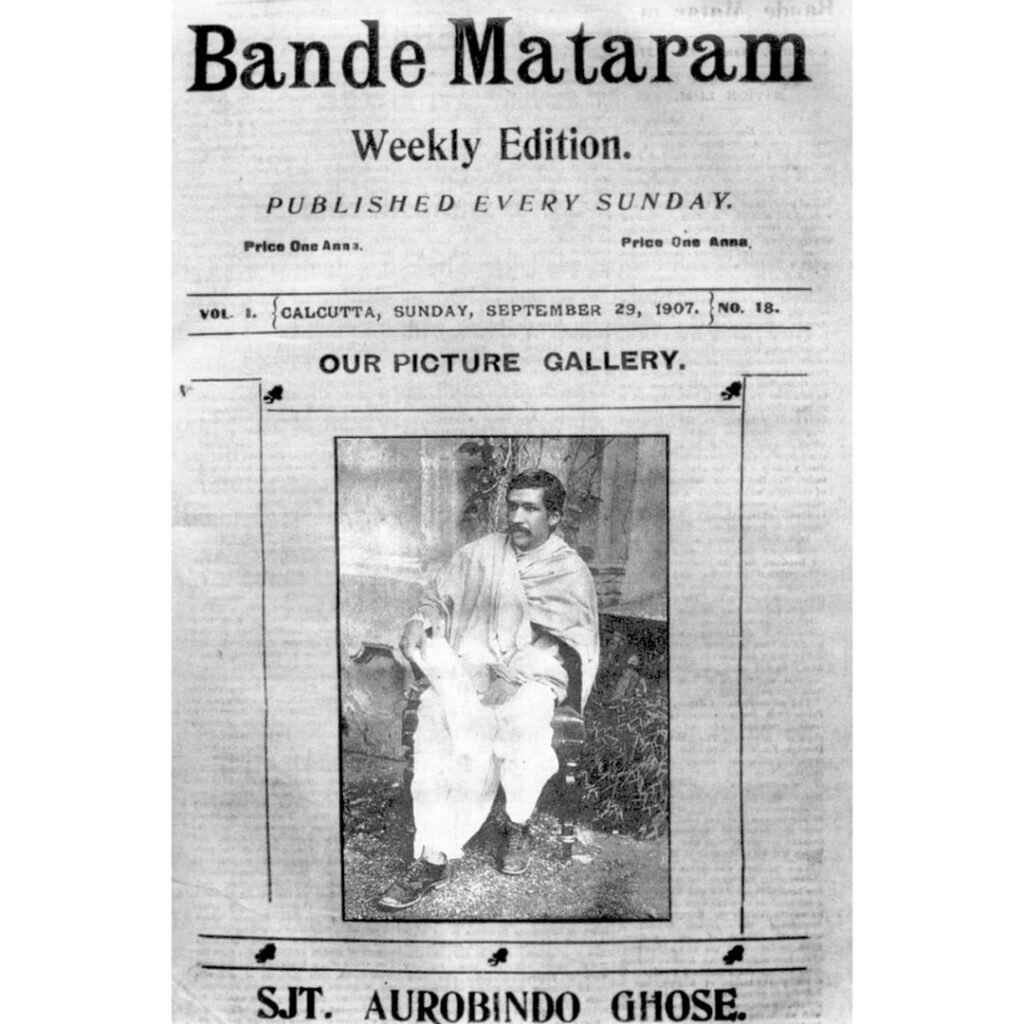

At this time, British India was at a crossroads. The country’s demand for freedom had become increasingly vocal; and some radical leaders of the Indian National Congress, like Lokamanya Tilak, were prepared to even support an armed uprising. In 1905, the British Viceroy, Curzon, further fuelled the outrage by bifurcating Bengal on religious lines. Naturally, Aurobindo was drawn to the patriotic cause. He had studied about Italian and Irish revolutionaries, and had been in touch with Tilak. He was convinced that Indians needed to shed their passivity and take bolder steps towards freedom. In 1907, he decided to quit his sedate college professor’s post and take up journalism. As the de facto chief-editor of Jugantar (Bengali) and Bande Mataram (English), two revolutionary publications, he wrote stinging reviews of the British dictatorship in India. This attracted a mass following of upper-class educated people. It also attracted the attention of the British Intelligence agencies who were eager to silence him. One other person who was charged up by Aurobindo’s thoughts was his younger brother Barin.

The Conspiracy

Barin became a core member of an organisation called Anushilan Samiti. It was ostensibly a ‘fitness club’, but really a secret society of militants. They attacked, robbed and sometimes killed British officers and their supporters. They smuggled arms and made bombs and stored them at an unused property of the Ghosh family in Maniktala.

Initially, their attacks were amateurish – like the attempt to blow up a train in which the Lt. Governor travelled. Barin then sent one of the members of the society, Hem Chandra Kanungo, to study bomb-making from a Russian revolutionary exiled in Paris. Now they were in the big league. They planned to kill Chief Magistrate Douglas Kingsford, who had been delivering harsh judgements on freedom fighters. The British received intelligence that Kingsford was at risk, and transferred him to Muzaffarpur (over 600 km away) and appointed bodyguards for him. Evading the bodyguards, two Samiti members, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki, monitored Kingsford’s habits before planning their attack. As Kingsford was returning from his club in his carriage, they darted from their hiding place and tossed a powerful bomb into the window, killing all the occupants. What they did not realise was that Kingsford was in an identical carriage, right behind. They had accidentally killed his bridge partners!

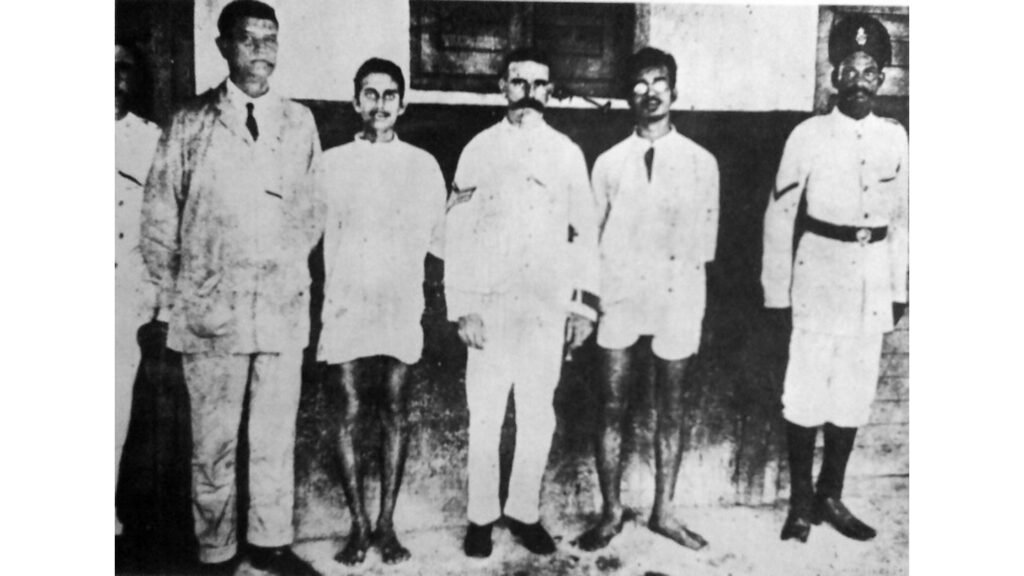

Khudiram Bose was apprehended by a police patrol at the local railway station. Chaki was surrounded by a police posse which lay in wait at Calcutta station, but he shot himself with his last bullet. The police raided many places and arrested 38 suspects associated with the Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar.

The Trial

Barin and another member of the Samiti, a bomb-maker named Ullaskar Dutt signed a confession with two others, saying that they alone were responsible for the attack. They knew they would be executed, so this stratagem was to save the others and the Samiti. If need be, they could later retract the confession on the pretext that the police tortured them. The British suspected that Aurobindo was the mastermind; and even if he wasn’t, they desperately wanted to implicate him. Unfortunately for them, none of the accused talked…at least in the beginning

The investigators sensed that one of the accused, Narendra Goswami, was vulnerable and pumped him. He agreed to draw information from Aurobindo (whom he hardly knew) and extract incriminating evidence. Aurobindo, who remained silent for most part, did not fall for the trap. Goswami nevertheless put together a mix of facts and fancies and was pardoned in return for the ‘disclosure’. Anticipating a revenge attack, he was moved to a special ward.

Meanwhile, Barin’s team had managed to smuggle pistols for a daring escape. But now the greater priority was silencing Narendra. Two volunteers, Satyen Bose and Kanailal Dutt, reported sick at the jail dispensary and sent word to Narendra saying they too wanted to switch sides. Narendra turned up immediately with a guard. After overpowering the guard, they gunned down Narendra. They then surrendered quietly to the warders and confessed to the murder. They divulged no information, and serenely went to the gallows later.

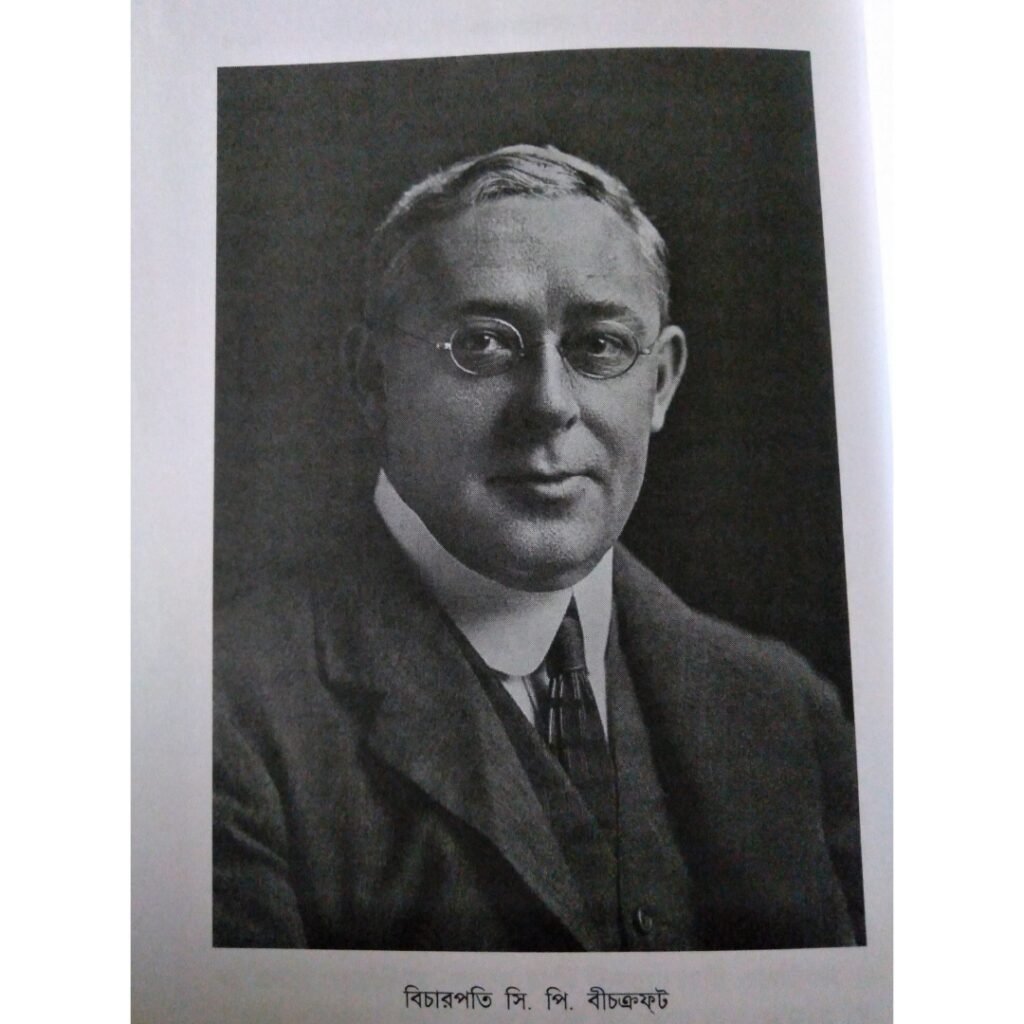

Ironically, the judge who tried the case at the Alipore Sessions Court in Calcutta was Charles Poten Beachroft, who had written the ICS exam with Aurobindo (and was ranked behind him). More strangely, the prosecution was headed by a brilliant barrister named Eardley Norton, who had argued many cases for Indian freedom fighters. His attempts to implicate Aurobindo became futile after Narendra was killed. The accused were stoutly defended by veteran Calcutta lawyer Byomkesh Chakravarty. Halfway through the case, Chakravarty resigned, when the accused could not pay their fees, and a junior barrister named CR Das stepped in. He continued the defence brilliantly, and later went on to become a famous lawyer, freedom fighter and poet!

The Aftermath

In May 1909, Beachroft pronounced his judgement. Barin and Ullaskar were convicted for life and deported to the Andamans. Another 19 were given punishments varying from deportation to the Andamans to simple imprisonment in Calcutta. Seventeen of the accused were found not guilty, the most important one being Aurobindo. It was mainly because of CR Das pointing out the lack of evidence against him.

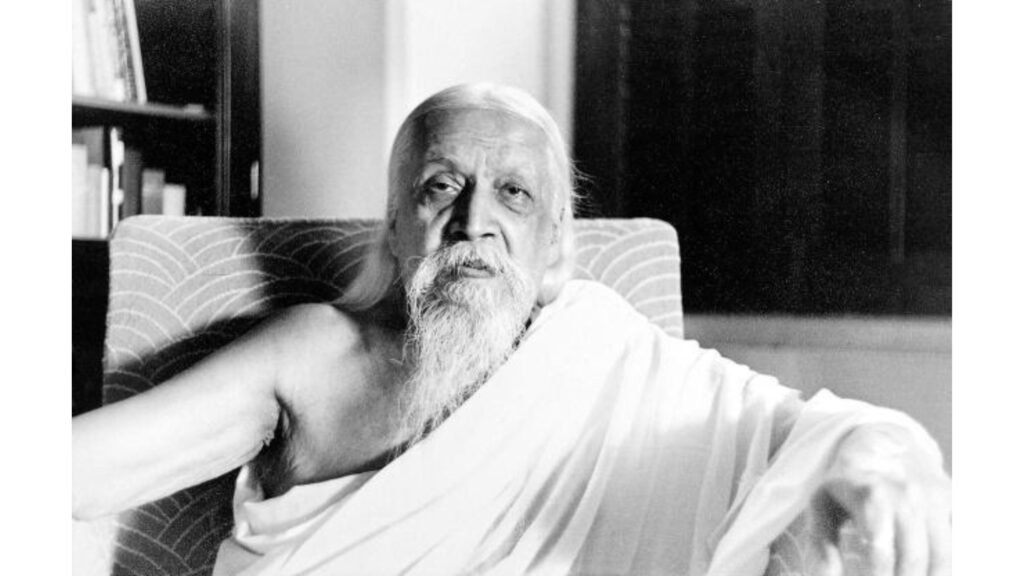

Aurobindo had started out as an agnostic, but his life experiences gradually turned him into a believer. Throughout his term in prison, he remained silent and serene. In his biography, Aurobindo states that he had some mystic experiences, including visions of Swami Vivekananda.

The British were extremely unhappy that they could not incriminate Aurobindo, and kept looking for opportunities to trap him. They need not have worried: his mystic experiences had turned him apolitical. Aurobindo later said that an inner voice urged him to go to Pondicherry. These were French colonies where fugitives from British India lived in safety.

Aurobindo secretly reached Pondicherry in 1910. He formed friendships with other freedom fighters like Subramania Bharati, VVS Iyer and Neelakanta Brahmachari. Gradually, he distanced himself from political issues and focussed on spirituality. He started a small ashram, which grew into an international spiritual centre that offered solace to seekers from all religions. Aurobindo died in 1950, but the ashram still welcomes thousands of devotees every year.

Aurobindo’s mentor, Tilak was wrongly implicated in the Muzaffarpur bomb case and was separately tried in Bombay (now Mumbai). Although barrister Muhammed Ali Jinnah put up a fine defence, the biased judge had Tilak exiled to the Mandalay prison during 1908-14 for instigating violence.

Barin and Ullaskar suffered terrible indignities in the Andaman prison. But in 1920, a general pardon was announced and they were repatriated to the mainland. Barin spent some time in the Aurobindo ashram and later became a journalist and author in Calcutta. The Anushilan Samiti continued its activities for many years, carrying out attacks on policemen, prosecutors, officers and British supporters. It gradually petered out in the 1930s. By then, most freedom fighters had switched to more peaceful methods.