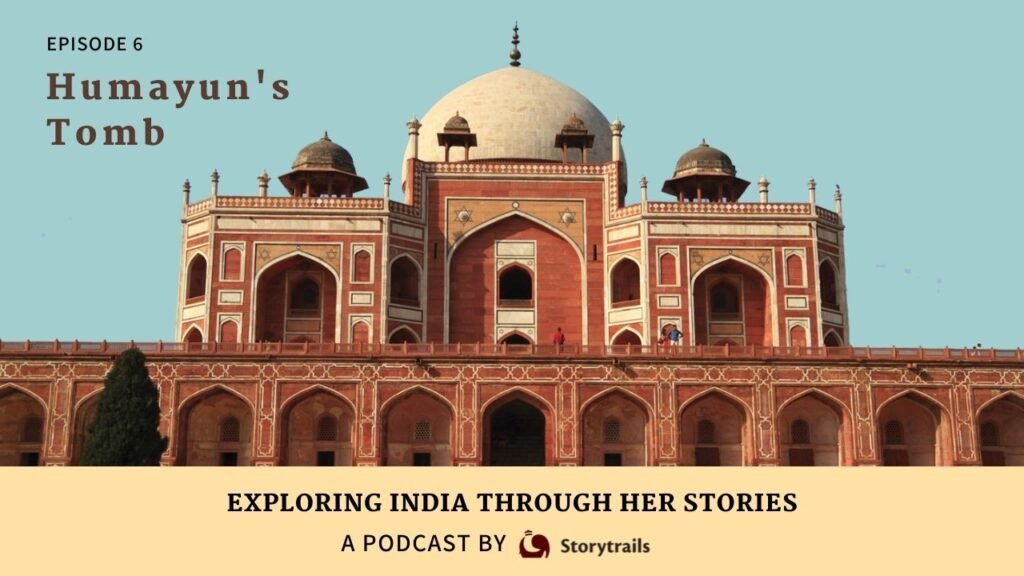

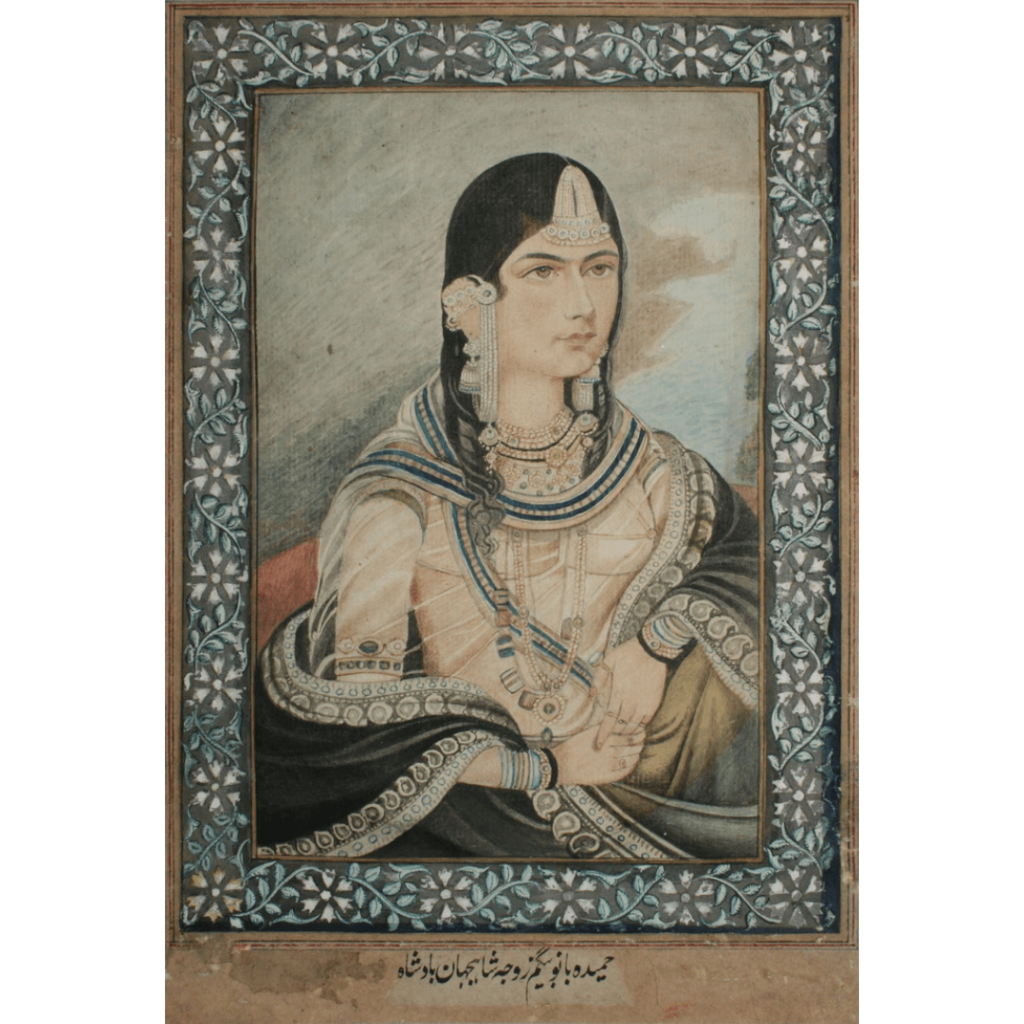

The name Humayun means “fortunate”, but ironically the life of this Mughal emperor was anything but that. Humayun’s life was filled with unfortunate events compounded with his own failings – poor judgement of people, substance addiction, procrastination and lack of focus. History books may project Humayun as a dull interlude that must be endured, sandwiched as he was between two very successful Mughal emperors – Babur the aggressive adventurer and Akbar, the astute administrator. But there were many interesting moments in his life, particularly his pursuit of love and his marriage to Hamida Banu Begum, the mother of the future emperor Akbar.

It was the year 1541. Humayun was on the run after losing major battles against the Afghan usurper Sher Shah Suri. After a very arduous journey, the fleeing Mughal entourage reached Sind where the Sultan of Thatta gave them refuge. Humayun’s immediate family and the family of his stepbrother, Hindal Mirza, found temporary peace. Hindal was once Humayun’s rival to the throne, but had now turned Humayun loyalist. Hindal’s mother (Humayun’s stepmother) Dildar Bano, arranged for a banquet to celebrate their deliverance. It was at the banquet, when Humayun first noticed Hamida Banu Begum.

Hamida was the daughter of the Hindal family’s respected family teacher – a Persian Shia Muslim and a Sufi spiritualist, named Sheikh Ali Akbar Jami. Both of them were invited to the party. Hamida was just 14, but her beauty and demeanour captivated Humayun. Humayun immediately pestered his stepmother Dildar to make a proposal for their marriage. At this time, Humayun was at his lowest point, having lost his throne recently, and forced to flee from Sher Shah’s forces. The fact that he could even think of adding another wife to his harem at this time was typical of Humayun.

It appears that Hindal was quite unhappy with the proposal. Some historians speculate that Hindal had a crush on Hamida. But that may not necessarily be true. Hamida’s and Hindal’s families were so close, that Hindal was possibly concerned for Hamida’s happiness like an elder brother. Would she adjust in an exiled king’s family? On the other hand, he could have also been worried about the Mughal family pride. In the Islamic tradition, the groom’s family had to offer mahr (bride price) befitting their status and honour. How could Humayun, an exiled king, offer a decent dowry? Humayun quickly brushed aside Hindal’s objections, saying they would manage it somehow.

Even Hamida had reservations about the match. Firstly, Humayun was 33, more than twice her age. This objection is documented in Humayun-nama, written by Gulbadan Begum, Humayan’s loving step sister. It has recorded Hamida as saying “I shall marry … a man whose collar my hand can touch, and not one whose skirt it does not reach”. Secondly, he already had a huge harem with many wives. Would he treat her well? When summoned by Humayun’s family, Hamida played hard to get. She said she had already paid respects to the emperor, and it was a sin to appear twice before the king.

But this was a battle Humayun was not willing to concede. He kept pursuing her with a determination that he had not even shown in war! Again, that was typical Humayun. Hamida held out for about 40 days, and in all that time, Humayun remained steadfast. He persuaded Dildar to talk to her. Dildar spoke to Hamida and told her that ultimately she would have to marry someone. Wasn’t it better if that person was a king who was willing and available? Hamida finally agreed. Humayun – an amateur astrologer himself – quickly took out his astrolabe and personally fixed an auspicious time for the wedding. The wedding was joyously celebrated, and they became an inseparable couple. Thereafter, she discarded all her reservations and never left his side, despite extreme hardships.

Humayun was still on the run, and soon they had to leave Thatta for another safe haven. The heavily pregnant Hamida travelled with Humayun across the Thar desert. On the way Hamida’s horse collapsed, and there was no extra horse. Humayun gave his horse to her and travelled on a camel with the others. Finally, they reached Amarkot where the local Rajput lord gave them shelter. Hamida soon delivered a healthy baby boy at the Rajput Lord’s house.

Humayun had great belief in astrology and mysticism. Once when Humayun was despondent, it is said that a spiritual man appeared in his dreams. He predicted that Humayun would get a son who would rule the world and advised to name him Akbar. The healthy baby boy born to Hamida and Humayun was none other than the great Akbar, the heir to the Mughal throne.

But there was no time to waste. Hamida was forced to leave the infant Akbar in Amarkot and flee to Persia. Askari (another step brother of Humayun) and his wife took Akbar to Kandahar to raise him. It must have been particularly heart-wrenching for Hamida to leave behind her new-born son, but her duty was to be with her husband.

The couple reached Persia where they were welcomed by the Shia king Tahmasp-I. Humayun was a Sunni Muslim, but Hamida was a Shia. This perhaps made Tahmasp kinder towards Humayun. He promised to help Humayun in his battles, if Humayun converted to the Shia faith. Humayun reluctantly agreed. Meanwhile, Humayun’s other brothers, Kamran and Askari (Akbar’s guardian) turned hostile in Afghanistan. So with Tahmasp’s support Humayun conquered Afghanistan defeating them, but his loyal brother Hindal was killed in action. After years of separation, Humayun and Hamida were joyfully reunited with Akbar.

In 1555, Humayun recaptured Delhi and became emperor again. Sadly, Hamida’s joy was short-lived. Humayun died within a year in a freak accident – he fell down the steps of his library at Purana Quila. But Hamida lived on for nearly 50 years more. She and Humayun’s step sister, Gulbadan went on a pilgrimage to Mecca – the sacred duty of all Muslims. As Queen Mother, she made significant interventions in politics, first when Akbar was an infant ruler, then when he ousted his regent Bairam Khan and later on behalf of her grandson Jahangir. Akbar always treated her with great respect and honour. When she died in 1604, she was buried with honours at Humayun’s Tomb.

*Postscript 1:

We know a lot about Humayun’s political life, because of the Mughal tradition of employing court chroniclers. We also have an interesting record of his family life from a biography written by his stepsister Gulbadan Begum (that roughly translates as ‘the princess who is lovely like a rose’). But it is no surprise that a Mughal princess wrote a biography. Mughal princesses were well educated, often managed their own finances, advised their husbands on key family and even public matters. They were respected by the male members, and were a binding force that held the clan together even during fratricidal succession wars. Akbar had great respect for his aunt Gulbadan, and he requested her to write his father’s biography, as she had been close to Humayun. It apparently also served as a reference to the chroniclers of Akbar-nama. And thus, she wrote Ahwal Humayun Padshah Jamah Kardom Gulbadan Begum bint Babur Padshah amma Akbar Padshah; or Humayun-nama, for short. It contains a candid commentary of Humayun’s relationship with Hamida. When the Mughal empire disintegrated, the document was lost. Col. GW Hamilton rediscovered a battered manuscript and it is now in the British Library in London. Although some pages are missing, it still provides a very vivid picture of life during the times of 3 Mughal emperors.

*Postscript 2:

Humayun became the Mughal emperor under a Mongol system of succession called Coparcenary inheritance. It did not prevent Humayun’s brothers from fighting with him. Watch this short video about the Mughal succession system that led to brutal fratricidal wars in successive generations:

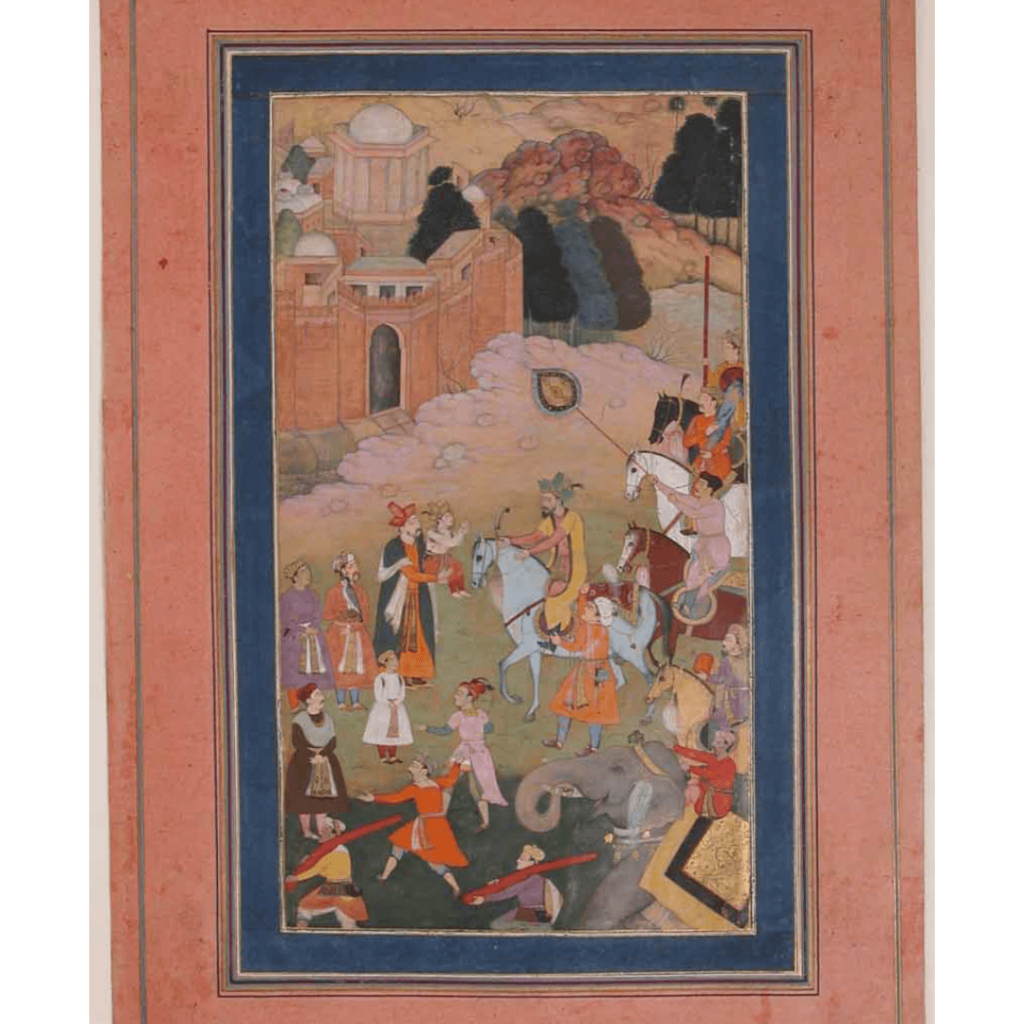

The triumphs and tragedies of Shah Jahan