Until 1925, it wasn’t uncommon for the kingdom of Travancore to have been ruled by powerful queens.

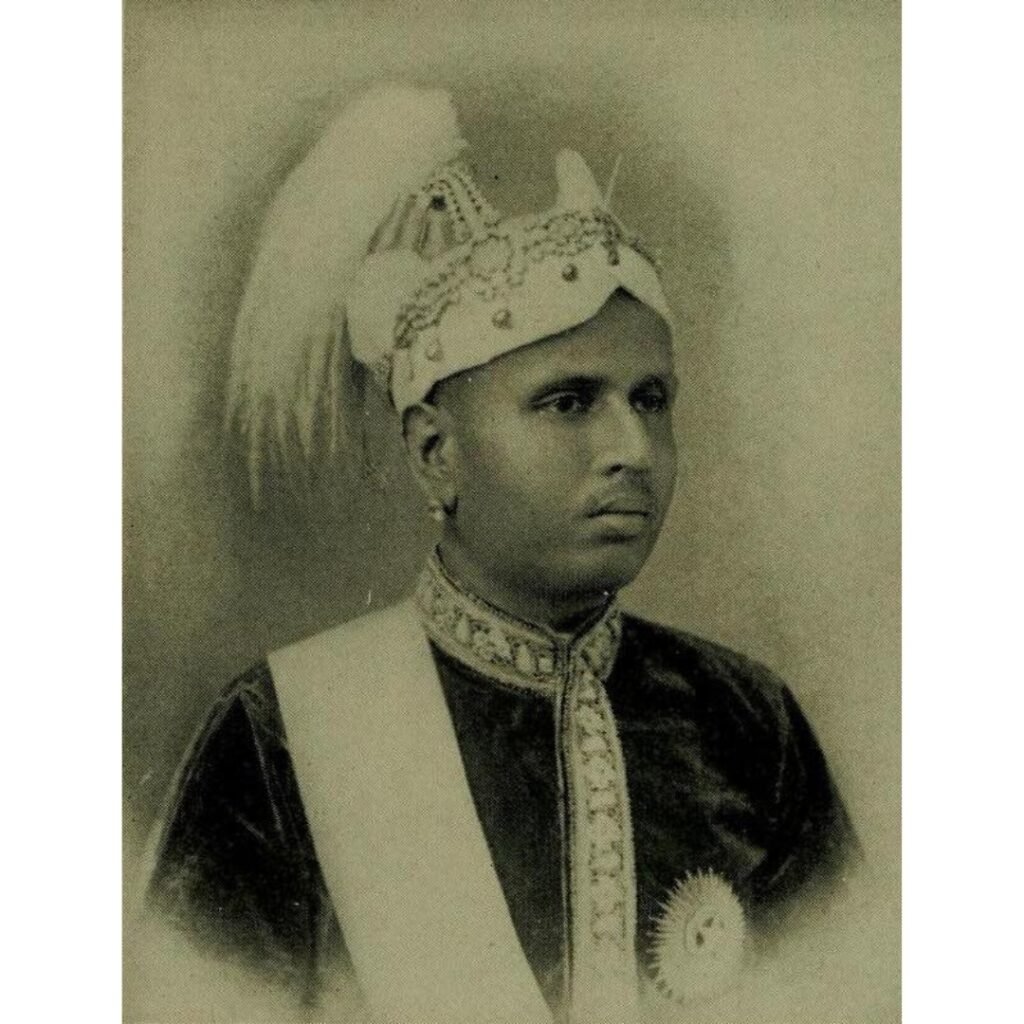

This story is about one particular queen – Pooradam Thirunal Sethu Lakshmi Bayi. The regent of the Travancore kingdom, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi was one of Travancore’s most dynamic rulers and ruled it from 1924 to 1931. Interestingly, she was not born into the ruling dynasty but was adopted into it. She became the queen because of a unique social custom practiced in Kerala called matrilineal succession.

According to the matrilineal system, the kingdom did not pass from father to son, but from mother to daughter. So, when a king died, his son would not become the next king. The crown would go to the dead king’s sister’s son, his nephew. His niece would be the future queen of Travancore. And she would go on to produce the next heir. So as you can see, the queens were all important, and producing a baby daughter was as important as producing a son. And if there was no baby girl born in the family, daughters were adopted into the royal family.

Detour: How did the matrilineal system in Kerala work?

In 1885, Maharaja Moolam Tirunal became the king. He had no sisters, which meant there was no one to continue the dynasty. Therefore, the Queen Mother had to adopt daughters. In 1900, she adopted two girls, the granddaughters of Raja Ravi Varma, the famous painter. And when the Queen Mother died, these two girls became the Senior Queen and Junior Queen – Pooradam Thirunal Sethu Lakshmi Bayi and Moolam Thirunal Sethu Parvathi Bayi respectively. The succession plan was clear. The Senior Queen Sethu Lakshmi Bayi’s son would become the next king.

As luck would have it, Lakshmi delivered daughters, not sons. Meanwhile the Junior Queen delivered a son, Chitra Tirunal Balarama Varma. Naturally, he was declared the heir-apparent. Sethu Lakshmi Bayi, it seemed, would now be just a ceremonial figure.

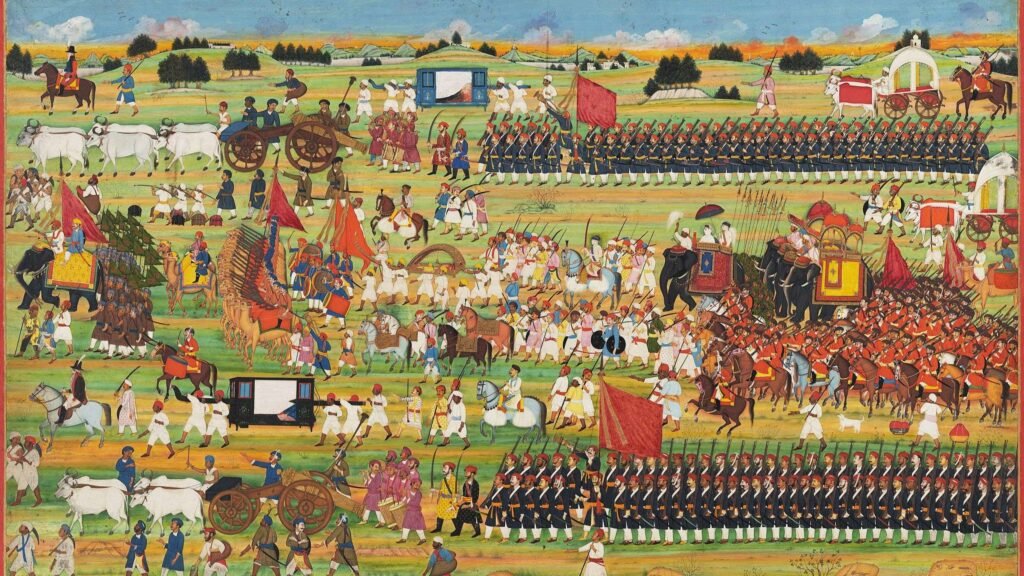

And then came another twist of fate. Moolam Tirunal died suddenly in 1924. This meant that Balarama Varma, the heir-apparent, had to be immediately crowned king. But Balarama was barely 12 years old, so a Regent was needed. And as the senior queen, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi outranked everyone else. She was appointed Regent Maharani of Travancore and that is how she became the most powerful person in one of the richest kingdoms of India.

Lakshmi was hardly 30 when she assumed charge; but she showed she was capable of taking on this job. She implemented sweeping social, political and economic reforms. And then, rather surprisingly, she abolished the very system of matrilineal succession that brought her to power.

The matrilineal succession system evolved from an era when wars and political instability were rife. Nair men were frequently at the war-front and a stable family life was near-impossible. So, a system evolved where men and women were free to adopt and terminate relationships through social contracts known as ‘Sambandams’. Moving into a relationship was simple and moving out was painless. Unlike the rest of India, even the death of the partner was not the end of the world. The system suited the times – it provided economic security, social stability, and liberated sexual choices, free of stigma, to the women.

But, by 1900, Kerala had experienced over a century of peace and the Nair men had settled down to quiet domestic lives. Without wars, they had begun educating themselves in English colleges in places like Madras (present-day Chennai), where they were perceived as an oddity. The patriarchal world saw these men as illegitimate children, born out of concubinage.

Even inside Travancore, intellectuals and reformists had started questioning the system. They felt that the Nair men were living off their wives’ inheritances. But it should be mentioned here that while the women owned the property, their power was not absolute. Routine management of the property and the household were entrusted to the Karanavar or the senior brother of the landlady. Over time, matrilineal families grew larger and more unwieldy. New issues arose. Some Karanavars were accused of favouritism. That resulted in many disputes over property, which in turn clogged the courts of the state. By the early 1900s, the Travancore government had come up with a modification that allowed men to bequeath what they had earned themselves, to their sons, and not their nephews. Clearly, the foundation of the edifice was shaking.

Sethu Lakshmi Bayi was sensitive to the changes around her. Finally, in 1925, she signed the historic Nair Regulation Act, which effectively ended the practice of matrilineal succession.