In 2016, Yale University, an Ivy League institute ran into an awkward situation. Scores of liberals loudly demanded that the name of Calhoun College, which was an affiliated college, be changed. Calhoun, a former US Vice President, had once declared slavery as a ‘positive good’ for America; this was against the very humanistic values that Yale University stood for. In 2017, the university removed Calhoun’s portrait from the college and changed its name. Little did they know that they had just opened up a Pandora’s box!

Yale University is named after an Anglo-American merchant named Elihu Yale. Back in 2007, the university had quietly removed a picture of Elihu from display, and replaced it with another. Why? Because the earlier picture showed Elihu and his friends being served by a dark-skinned boy, possibly of Indian origin. A metallic clamp-with-lock on the boy’s collar pointed to the fact that he wasn’t just a servant, but a slave.

Now, after the Calhoun incident, the university was asked why they wanted to bear the name of a slave-owner. The university’s first defence was that Elihu was not technically a slave-owner. That was perhaps true. But further research showed that he was, in fact, much worse! Elihu had presided over a huge slave racket, where slaves were whipped, branded and ill-treated.

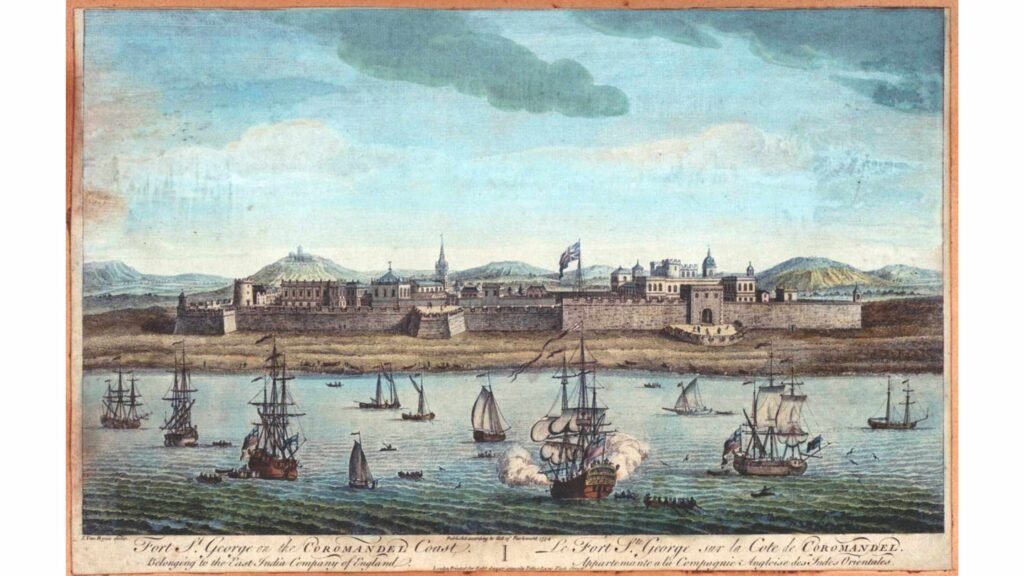

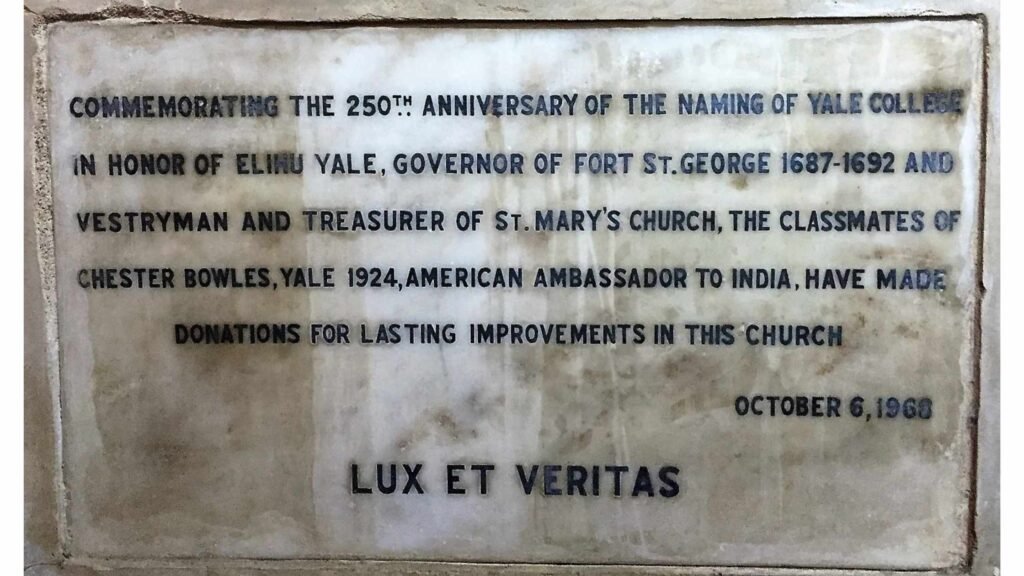

Elihu was the son of a rich Boston merchant. He started his career in the East India Company at the British colony of Madras (modern Chennai). In the 1680s, Madras was in the grips of a famine; naturally, unemployed youth flooded the slave market. Elihu and his colleagues sent hundreds of them to other British colonies. Initially, only petty criminals were enslaved; but as demand for slaves increased, even young children were sent to remote destinations, never to return. This continued when Elihu became Governor of Madras in 1687. He was even party to a company rule that every ship leaving Madras should export at least 10 slaves!

Suddenly, in 1688, Elihu ordered that the slave export be stopped. It was not out of remorse. In those days, the British colonies were under an Indian king’s licence. The Indian ruler who now controlled this region was the mighty Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. He considered slavery inhumane, and banned it. The British didn’t dare to disobey him. Moreover, the famine had passed, and it had become difficult to capture slaves. Elihu made the withdrawal seem like any other commercial decision: ‘the (slave) trade had become more trouble than it was worth’.

By then Elihu had enriched his employers and himself by trafficking human cargo. In those days, a majority of the Western society did not consider slavery immoral; and Elihu was part of the majority. However, his professional and private lives were scandalous too. Elihu constantly violated company rules by conducting illicit personal trades that competed with the company’s business. His private business was large and profitable, but he needed capital. This, he managed by marrying his best friend’s widow. She came with a huge inheritance, and Elihu shamelessly exploited her wealth. After grabbing what he needed, he quietly shipped her off to England and took two mistresses. One mistress was the wealthy widow of a successful Jewish diamond merchant. For Elihu, her inheritance was a timely source of capital; and she was also a valuable source of useful business contacts in the diamond trade. His other love interest too was a businesswoman in her own right and supported him in his wheeling and dealing.

How long can private misdemeanours remain private? Eventually, members of the Governor’s Council complained, and the company’s board of directors dismissed him in 1692. And justice was served…? Not really. Elihu pulled some strings and cleverly (and successfully) defended his case with the help of his influential friends. And he managed to even continue his shady deals till 1699! By this time, the complainants in the Madras Council had died. Now, Elihu Yale returned to England filthy rich, and settled in a mansion at Queen’s Square. He was nicknamed ‘the Nabob of Queen’s Square’!

Elihu had plenty of money, but now he yearned for respectability. So, when the Connecticut College approached him for a donation, he sent them a consignment of books, paintings and other artefacts. The goods were auctioned off, fetching roughly GBP 800. That was a very small portion of his ill-gotten wealth, but it was a princely sum for the college: it funded the erection of a whole new building. The attractive part of the deal for Elihu was that the Connecticut College would be renamed Yale College. Yale College subsequently became the famous Yale University. In his old age, Elihu had negotiated his greatest deal: a paltry donation in exchange for everlasting fame! Nearly three centuries later, the American Heritage Magazine described Elihu Yale as ‘the most overrated philanthropist’!

Watch this short video for more on Elihu Yale: