The Mughal emperor Aurangzeb had three brothers and three sisters (Shah Jahan and Mumtaz had fourteen children in all, but seven of them died during infancy). His equation with his brothers was simple: they were rivals who had to be eliminated. His eldest brother Dara Shikoh was beheaded and another brother, Shah Shuja, mysteriously vanished at the Burmese border while fleeing Aurangzeb’s army. And his younger brother Murad Baksh was quietly executed in Aurangzeb’s prison.

His relationship with his sisters, however, was complex. Instead of marrying and migrating, they remained spinsters in the capital. They were, however, not necessarily celibate – they had affairs and that had some consequences. While Mughal records were silent about these, contemporary European travellers recount tales of their romantic escapades.

The sisters played a significant role in Aurangzeb’s life. In fact, the system was loaded against their getting married. Tradition required them to marry a royal who was equal or above their status. By the mid-17th century, the Mughal empire included large parts of Hindustan, Pakistan and Afghanistan, covering over 3 million square kilometres. Where would they find a compatible groom in the neighbourhood? (On the contrary, Mughal men could, and did, marry princesses of lesser kingdoms and filled their harems!)

In 1631, their mother, Mumtaz died while delivering baby Gauhar Ara. Shah Jahan went into deep depression. The new-born Gauhar needed immediate attention, and somebody had to hold the family together. Jahanara, inexperienced and just 17, took charge. She nursed Shah Jahan back to health, and became a maternal guardian to the younger siblings. Even Aurangzeb would confide in her (he was often an ‘injured’ party because Shah Jahan never openly showed him affection ). Jahanara was the tolerant, conciliatory, mother figure of the family.

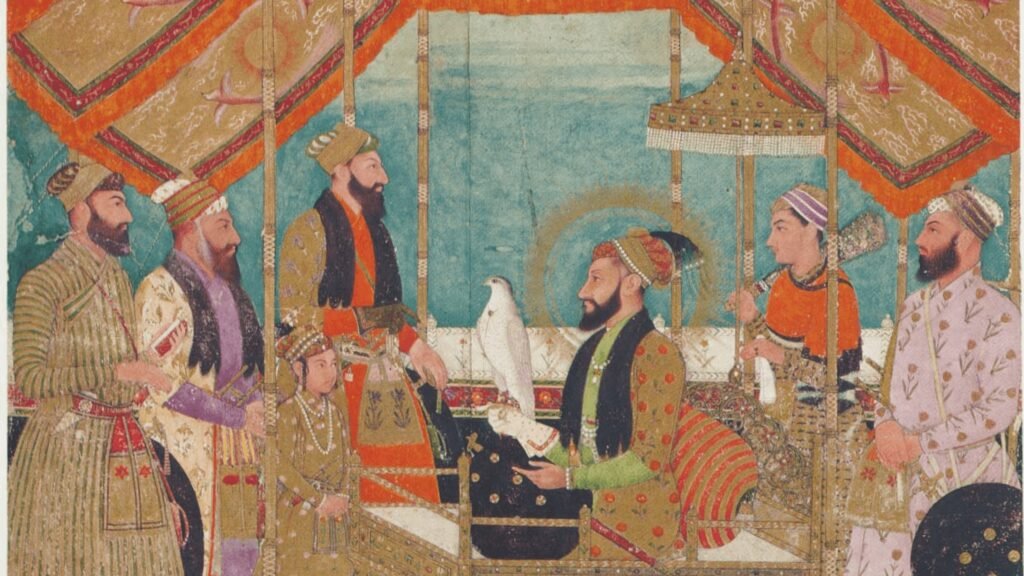

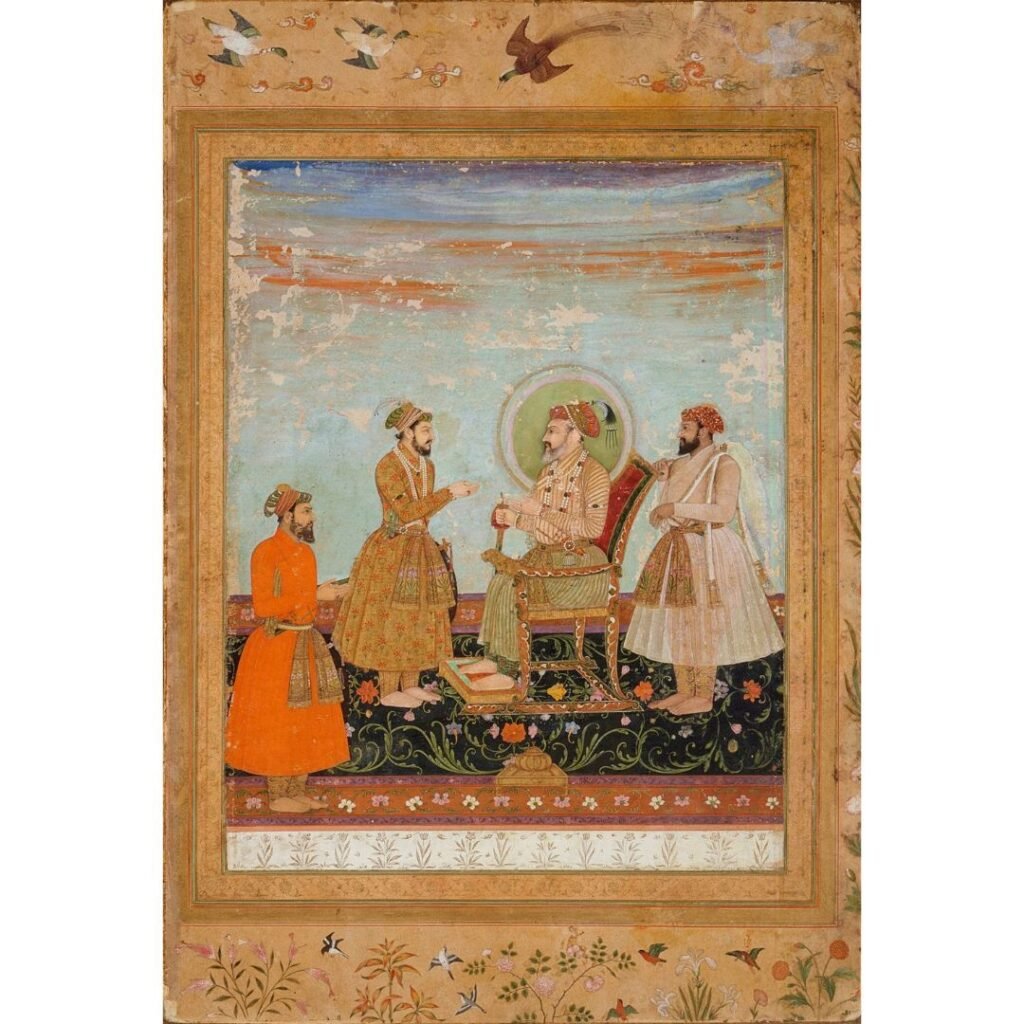

When normalcy returned, Shah Jahan made Jahanara the Padshah Begum (‘First Lady’). This was no honorific title: it was the second most powerful post in the empire. She could pass certain orders independently, make recommendations to the emperor, and perform certain actions in his absence. Shah Jahan also gave over half of Mumtaz’s estate to Jahanara, dividing the balance between the other siblings. She turned out to be a good entrepreneur, even earning good profits through a ship she owned in Surat. She spent her fortune usefully, supporting famine relief, pilgrimages and almsgiving, sponsoring mosques and overseeing the development of Chandni Chowk. Jahanara also wrote many books, including a respected biography of the Sufi saint Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti.

One person was bitter about Jahanara’s huge popularity: Aurangzeb’s other sister, Roshanara. She was the antithesis of Jahanara: feisty and fun-loving, but resentful of the fact that she had to live in Jahanara’s shadow. She too loved poetry, and was a clever businesswoman. She found a natural ally in Aurangzeb who shared a similar grudge: Dara got all the cushy assignments in the government, while Aurangzeb got all the complex tasks, with no appreciation. Shah Jahan’s favourite was clearly Dara, not Aurangzeb.

Dara was very different from Aurangzeb. He loved poetry, and dabbled in Sufism and other religious philosophies. He lacked Aurangzeb’s military and governance skills, but was not above manipulating his father’s sympathy to his advantage. At one point he and Shah Jahan plotted to eliminate Aurangzeb from the imperial race. Roshanara got wind of the conspiracy and warned Aurangzeb. She also turned the Muslim clergy against Dara by pointing out that his secular activities were anti Islam.

Detour: Watch this video to know of the circumstances that catapulted Shah Jahan to the throne of the richest kingdom in the world, but reduced his personal life to a terribly tragic one.

The casualty in this whole affair was Jahanara. It was unlikely that she was involved in any conspiracy. But she was perceived as ‘pro-Dara’, which in Aurangzeb’s books read as ‘anti-Aurangzeb’. Born within a year of each other, Jahanara and Dara had not only grown up together, but they also shared a common love for poetry and Sufism.

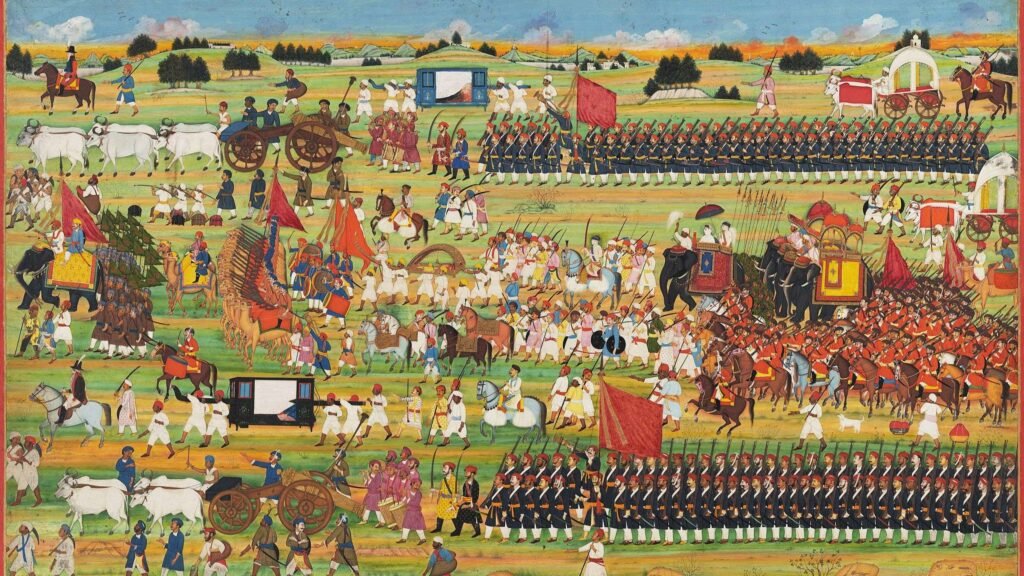

In 1657 the brothers started fighting for the throne, even when Shah Jahan was alive. Jahanara, although close to Dara, tried to stop the fratricidal wars. She appealed to Murad and Shah Shuja, quite unsuccessfully, to stop fighting. Aurangzeb arrived with a powerful army to fight Dara and Shah Jahan. Jahanara appealed to Aurangzeb not to fight his own father; she proposed a partition of the land among the four sons (like their ancestral Timurids would have done). She received a cold reception from Aurangzeb – he now perceived her as part of the enemy camp. He denounced Dara as an infidel (Roshanara’s smear campaign had worked!). Aurangzeb would settle for nothing less than the whole empire.

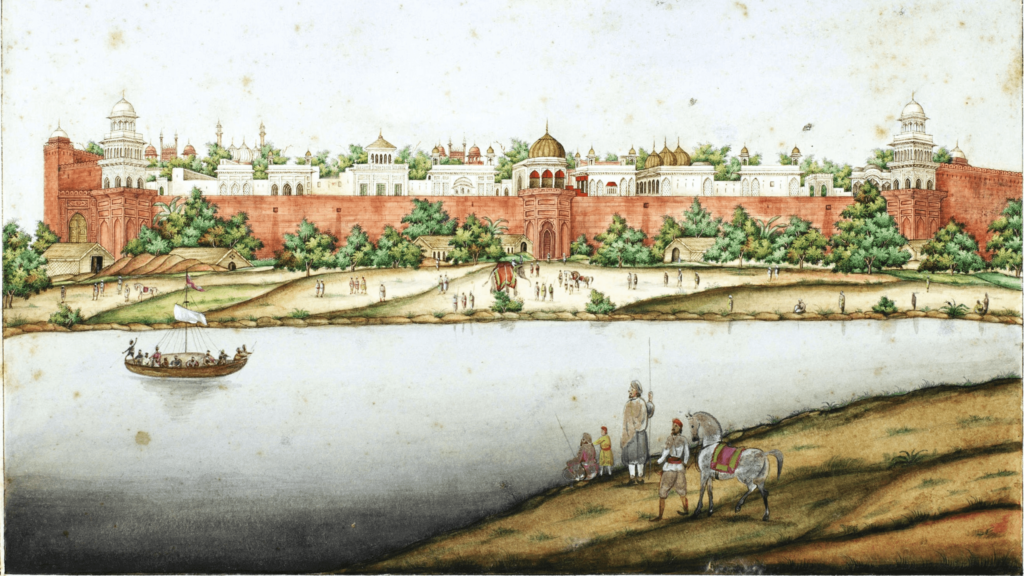

In the battles that ensued, Aurangzeb captured Dara. Some scholars believe that Roshanara egged Aurangzeb to behead Dara (in all probability, Aurangzeb needed no prompting, though). Shah Jahan was placed under house-arrest in Agra, and Jahanara voluntarily accompanied him to look after him. In any case, Aurangzeb dismissed Jahanara from the Padshah Begum post and appointed Roshanara instead. Finally, Roshanara was out of Jahanara’s shadow!

Roshanara did not make a great First Lady. When Aurangzeb was away, she passed orders that suited her personal interests and enriched her coffers. There were allegations of corruption. As the head of the royal harem, she rode rough-shod over the ladies and incurred their displeasure. She was still young and attractive (just over 40) and had flings which were grist for the rumour mill. This was too much for Aurangzeb who was inherently austere to the point of asceticism. In 1667, he dismissed her from the Padshah Begum post and banished her from the Red Fort. She settled at the Roshanara Bagh, a lovely jungle villa she had built for herself. She died in seclusion in 1671, aged only 54. Some historians believe she was discreetly poisoned under Aurangzeb’s orders.

Shah Jahan died a prisoner in 1666, and Jahanara’s mission was over when she arranged his funeral. Aurangzeb re-appointed Jahanara as the Padshah Begum. It was his way of admitting that he had judged her wrongly – a remarkably un-egoistic admission from the dictator. She resumed her good work in government service, even occasionally moderating Aurangzeb’s ultra-orthodox and extreme measures. She died peacefully in 1681.

Now about Gauhar Ara, Aurangzeb’s little sister. Because she was little, she missed all the action in the early part of our story. When she grew up, she took a leaf out of Jahanara’s book, working for family unity. In 1673, she played the lead role in conducting the marriage of Prince Sipihr Shikoh (son of Dara Shikoh) and Princess Zubdat-un-nissa (Aurangzeb’s daughter). Strangely, it did not matter that Sipihr had witnessed his father-in-law beheading his father. What mattered was that Zubdat-un-nissa had married a royal of equal status! Gauhar adopted and raised Dara’s granddaughter Salima Banu, and conducted her wedding with Aurangzeb’s fourth son, Muhammad Akbar.Aurangzeb’s relationship with Gauhar was not as intense as with the other two sisters. Yet when she died in 1706, he lamented, ‘Of all the children of Shah Jahan, she and I alone were left.’ Aurangzeb was a man of contradictions: ruthless and greedy for power, he did not care for money, but lived frugally as a pious Muslim. He killed his brothers and did not know how to love his sisters, but rued his loneliness after his last sister died. He died within a year and was buried in a simple grave.