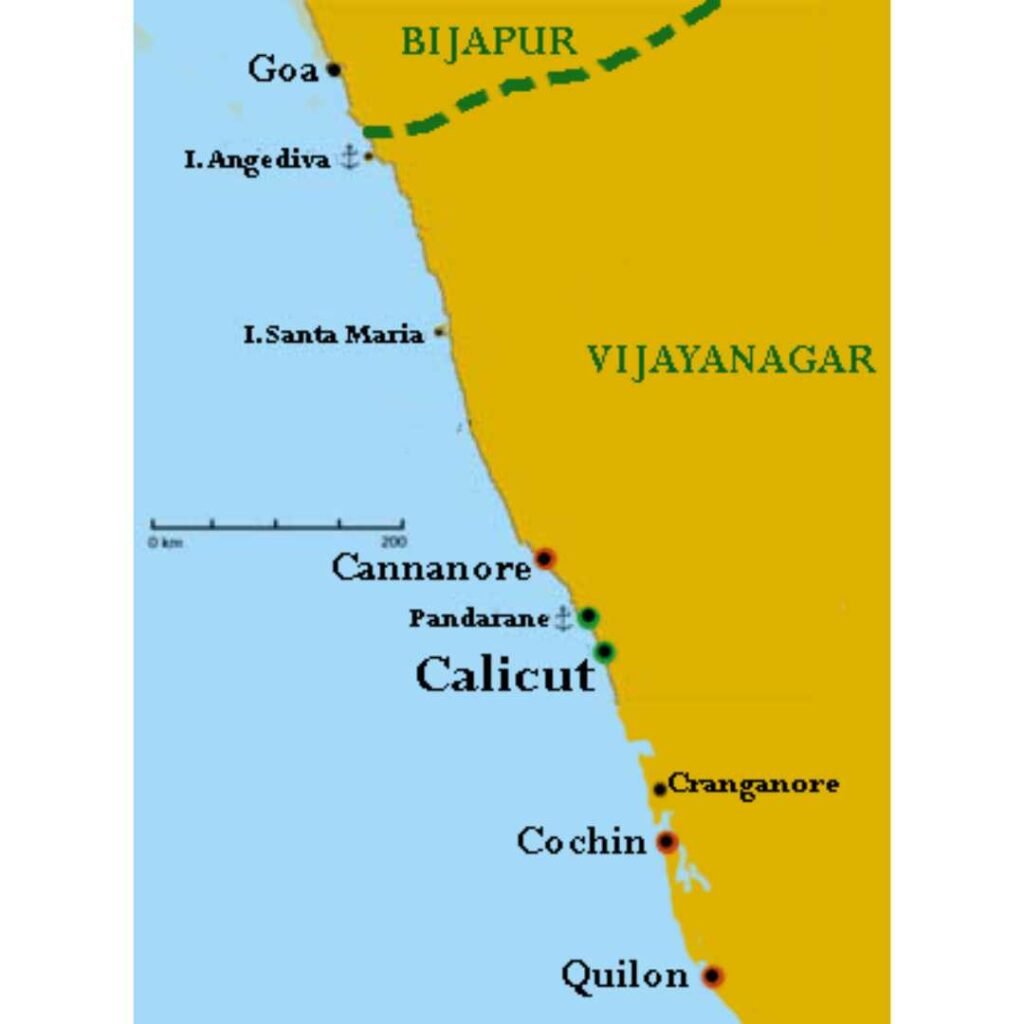

Around 1497-98, the king of Calicut (in India’s south-western coast) was a key player in the world spice trade. His honorific title was “Samuthiri” (or Zamorin). The Portuguese sent their envoy, Vasco da Gama, to win trading concessions from him. But Vasco messed up and ended up completely antagonising the Zamorin. The desperate Portuguese sent another envoy to Samuthiri’s rival, the king of Kochi (formerly called Cochin) in 1500 and a trade-cum-military pact was signed. Naturally, the Zamorin was not pleased.

The Portuguese armada returned home in 150, and Kochi was vulnerable to attacks till the next Portuguese armada arrived. The Zamorin chose this moment to attack Kochi with 60,000 soldiers and 250 naval boats. The Kochi king had only 5,000 soldiers and the Portuguese reserve force was only made up of 200 men and five naval vessels under Captain-Major Duarte Pacheco Pereira. The situation seemed hopeless, yet Pacheco convinced Kochi to stand fast!

Pacheco was not a mere soldier but a remarkable scholar and strategist: he had been the Portuguese court geographer, and a cartographer who had studied astronomy and oceanography. His scientific journals covered the lunar effect on tides, the ability of chimpanzees to build hand tools and other such exotic subjects! According to some historians, he landed in Brazil before Pedro Alvares Cabral (the official discoverer of Brazil) did! But could a scholarly expert defeat brute military superiority?

Pacheco guessed that the Zamorin’s huge army would pass through a narrow riverine pass called Kumbalam to reach Kochi; in that narrow pass they would be extremely vulnerable. Pacheco’s men took hidden positions and waited there. As the Zamorin’s men arrived, Portuguese snipers effortlessly killed 1,300 enemy soldiers.

Pacheco realised that the Zamorin’s state-of-the-art Italian field-guns had a deadly range and accuracy; so, he ordered his snipers to ceaselessly fire at the artillery crew, never allowing them to settle down. By the time the Calicut artillery finally organised itself, Pacheco had already invented another new tactic.

In a crucial naval battle, all Portuguese guns suddenly went silent. The Zamorin’s commanders assumed that Pacheco had run out of ammunition, and closed in to “finish off” the Portuguese ships. They had actually fallen for a trick: when they approached point-blank range, the Portuguese gunners went ballistic and blew up most of the Calicut navy. No Italian technology could save them.

Kochi is surrounded by creeks and inlets. Pacheco had mapped the tides and currents at all fords and creeks, and knew how best to defend these spots. This meant that Pacheco’s tiny but agile force could cause devastating damage via guerrilla attacks on the widely spread opposing army. Size had become irrelevant!

Between March and July 1504, Pacheco used his local geography-oceanography knowledge to play mind games and demoralise the enemy. Then, the monsoons arrived and an epidemic of cholera erupted in the Zamorin’s camp. By now, he had lost nearly 20,000 men — 13,000 to cholera alone. This was too much for the king; he abdicated his throne in favour of his nephew and turned to religion. When the Portuguese armada returned in August, they found Kochi happily celebrating their victory!

The Siege of Kochi altered Indian power equations forever. The Zamorin ceased to be the game-changer of pepper trade, and Kochi became a new power player. Most importantly, the Portuguese became a feared colonial power.

After his heroics in Kochi, Pacheco returned to Lisbon. The king of Kochi gave him an emotional farewell and King Manuel I of Portugal conferred an honour on him. He later became the governor of a Portuguese colony in the Gold Coast (Ghana). However, his success brought the wrath of powerful enemies in Lisbon upon him. These jealous nobles foisted false charges of corruption on him and he was dismissed. His original sponsor, King Manuel I, had died and the new king did not realise Pacheco’s value. Although he was proved innocent some years later, Pacheco had lost all his power and wealth by then and died in obscurity.