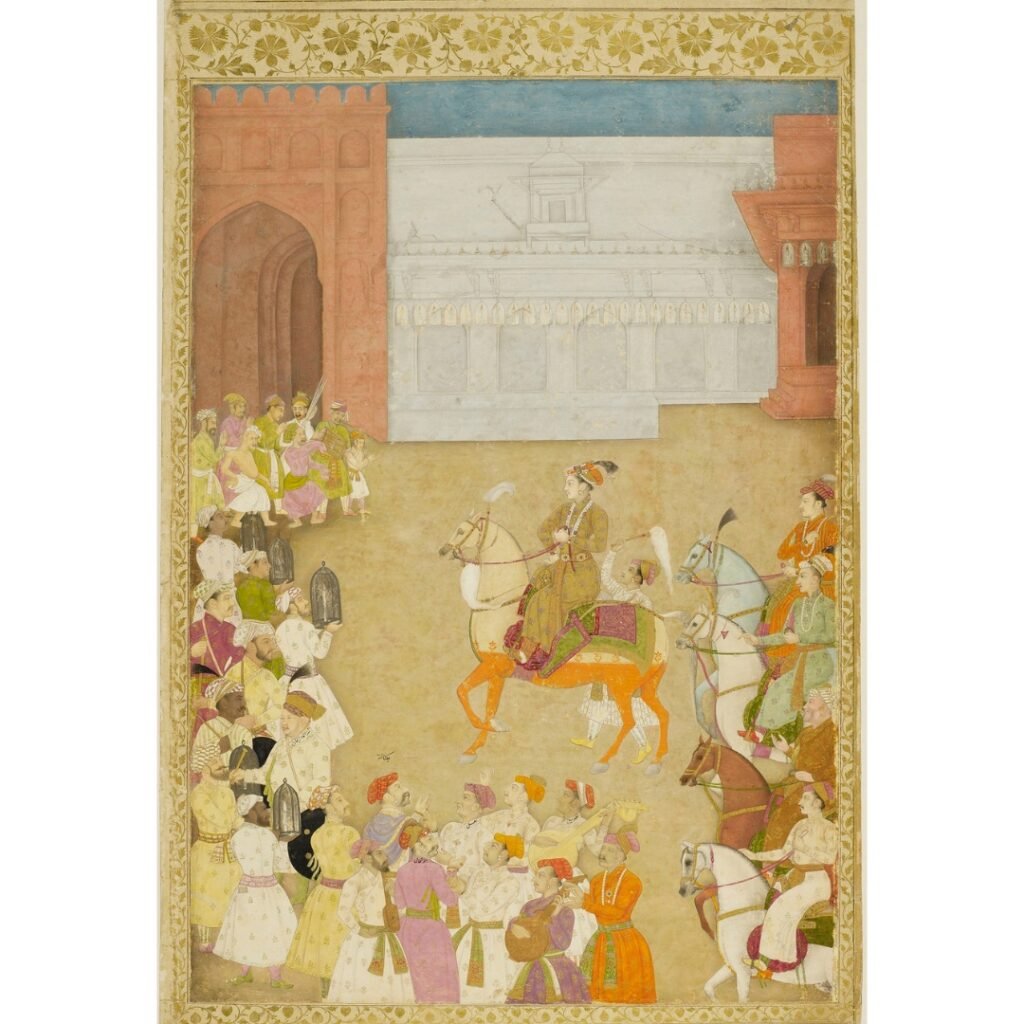

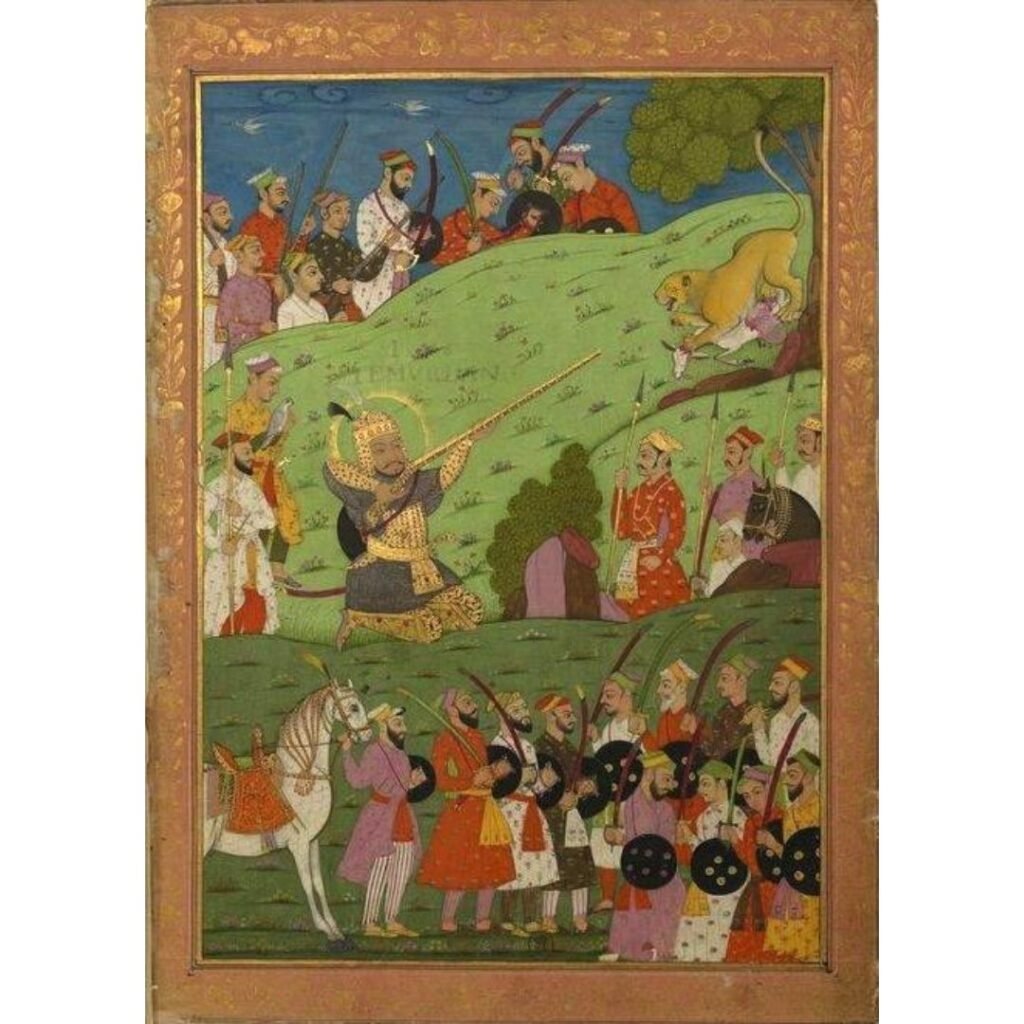

Historians know more about the Mughal dynasty than any other dynasties. One reason is that apart from the royal chronicles, there are a number of independent accounts of their lives and times written by foreign travellers. By the 16th century, India had seen many European travellers, who came here for trade, employment and evangelisation. A large number of them spent time in the Mughal kingdom mainly because it was more prosperous.

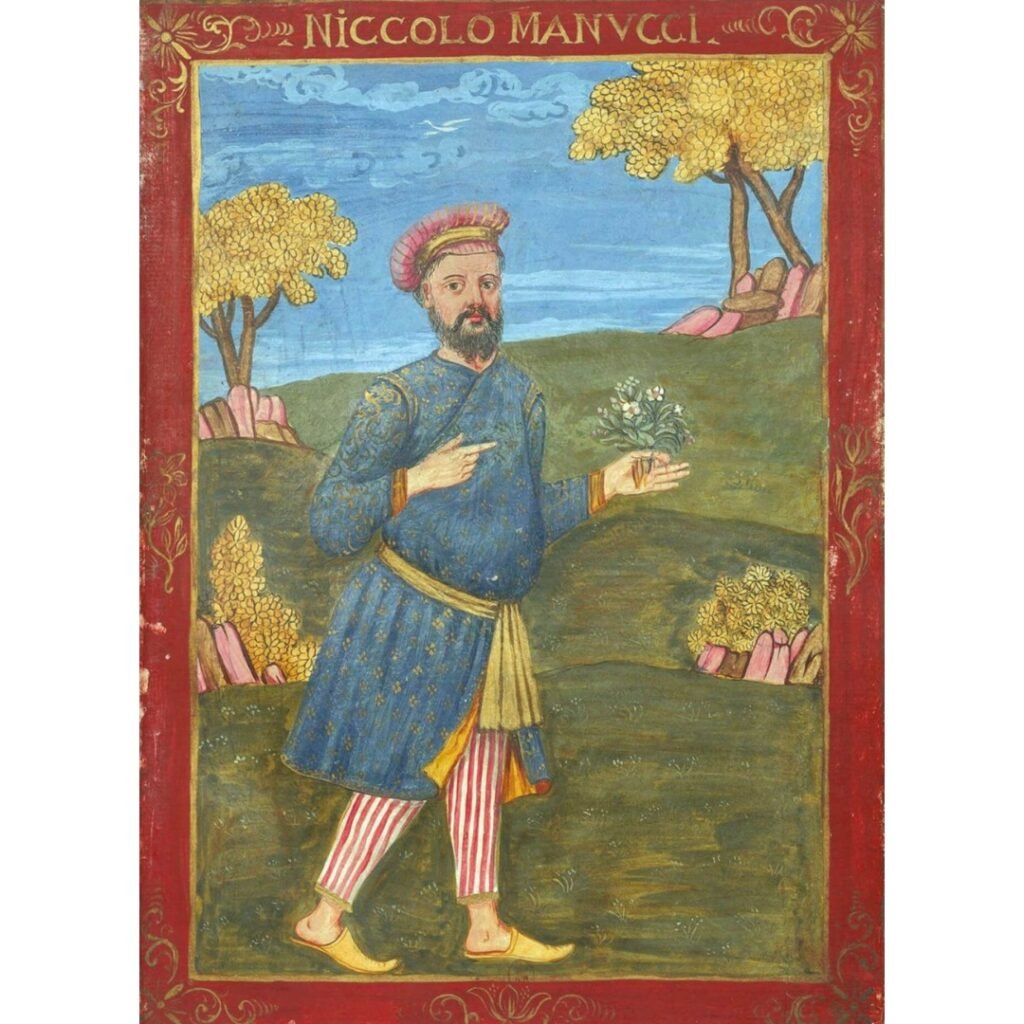

One such traveller was a man named Niccolao Manucci. He was an Italian artilleryman, employed in the services of the Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, who was eventually defeated by his brother Aurangazeb.

According to Manucci, he was offered the chance to join Aurangazeb’s army but he decided to flee instead. In his memoir, Storia de Mogor (or Story of the Mughal), Manucci paints a fabulous picture of his life and casts himself as the long-suffering hero and Aurangazeb as the evil villain, his arch-nemesis. But can we believe him blindly?

Time obscures the past from the present; therefore, it is the historians who must squint and puzzle out the blurry events of history. First-hand accounts of travellers provide useful insights into life during an era. But travelogues like the Storia are also often full of completely fabricated details, which makes the job of historians much harder!

Consider Marco Polo, one of the most iconic figures in history, an Italian merchant who visited the Mongol courts and travelled the length and breadth of the Silk Road. He is probably the most famous traveller in history and a common figure in school textbooks. But did you know that when he saw rhinos, he thought they were really ugly unicorns?

Niccolao Manucci was no different. His memoirs are full of factual errors and colourful lies. But through the work of scholars, it’s possible to piece together some key details. Manucci was born in 1638 in Venice and came to India when he was just 17. He landed in Surat and was employed by Dara Shikoh. After Shikoh’s defeat, he worked for the Rajput king Mirza Raja Jai Singh, but this stint too did not last long. Manucci’s travels and quests for employment took him from all over India – from Kashmir to Bengal, and Goa to Madras (present-day Chennai).

The Italian tried to move to Goa, probably to be closer to other Europeans, but despite multiple attempts, he was never able to successfully plant roots in the Portuguese enclave. Instead, he worked for other Muslim rulers in Lahore and then the Deccan. Because he was Italian and thus unaligned with any particular power in the subcontinent, he was able to move freely between kingdoms and rulers. But his constant jumping back and forth between European and Indian employers soon meant that he wore out his welcome with both. And so, in the 1680s, Manucci fled to the south.

It was in the south that Manucci finally settled down. He was close friends with the founder and governor of Pondicherry, Francois Martin. And he developed a good working relationship with the English East India Company, using his experience to act as their intermediary with the Nawab of Arcot. He married, grew wealthy and built two houses – one in Pondicherry and one in Madras on St. Thomas Mount (or Parangi Malai, meaning ‘foreigner’s hill’). He also earned a reputation as a physician, combining stray bits of Siddha, a medicinal tradition native to South India, that he had learned from local practitioners and whatever tricks that had worked for him over his many decades in India. Because he had no formal training, he was more quack than doctor, but that didn’t seem to stop him from garnering some level of success.

It was when he was in Madras that he began writing his epic work, Storia do Mogor. As he finished each volume of the book, he would send it by ship back to Europe to be published. He might have written even more if not for a personal tragedy struck. In quick succession, he lost his wife, Elizabeth, as well as his close friend, Francois Martin. Ironically, his self-proclaimed nemesis Aurangazeb also died around the same time. Manucci himself probably passed away in Madras around 1720.

The five volumes of the Storia are a fascinating view into the 17th-century world of India, but without scholars and historians who quietly piece together the truth, they would be as unreliable as weather forecasts of the rain!