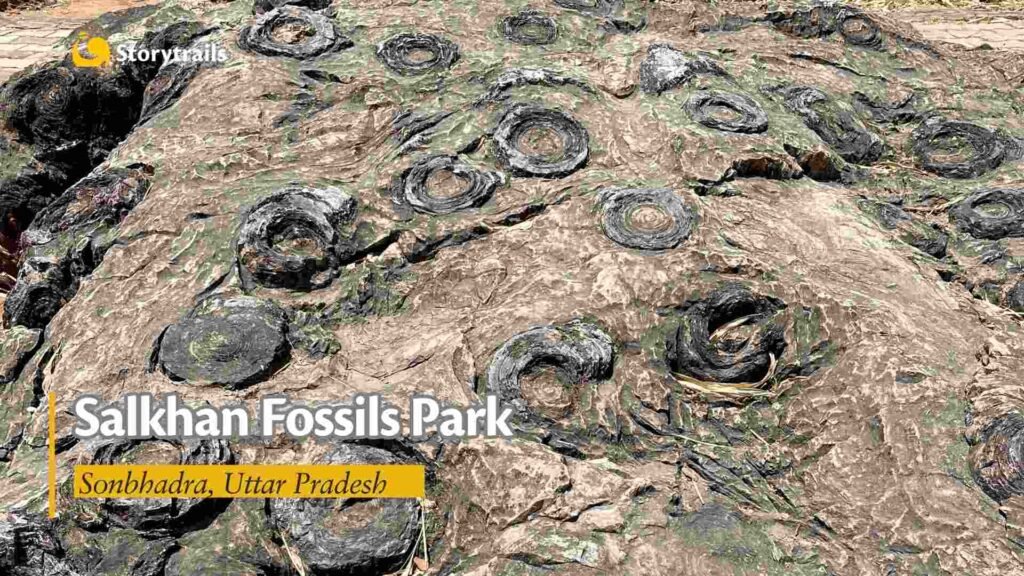

On 13 April 1919, a peaceful unarmed crowd gathered at Jallianwala Bagh, a park in a congested locality of Amritsar. Many had come to demand the withdrawal of the emergency-like restrictions that had been imposed on Indians by the British. It rankled especially because these restrictions had been laid down despite the huge Indian contribution to the British success in World War I). Others had come to celebrate the spring festival of Baisakhi. The local commander, Brigadier Reginald Dyer branded them all as terrorists and brought out the army, when even police action was unjustifiable. They blocked the gates and fired till all of their 1650 rounds of bullets were exhausted, leaving 380 dead and 1200 wounded, including women, children and elderly folk.

Brigadier Dyer was fully backed by his boss, the despotic Punjab Lt. Governor, Michael O’Dwyer ICS. They quickly hushed up the massacre by imposing martial law and press censorship. But one courageous British journalist named Benjamin Horniman exposed the ugly truth to the world. Lord Chelmsford, the British Viceroy who was actually working on administrative reforms, was greatly embarrassed. The Viceroy’s Council had 5 members at that time, and Chettur Sankaran Nair was its lone Indian member. When the news ultimately reached him, he was so appalled that he wanted to resign immediately.

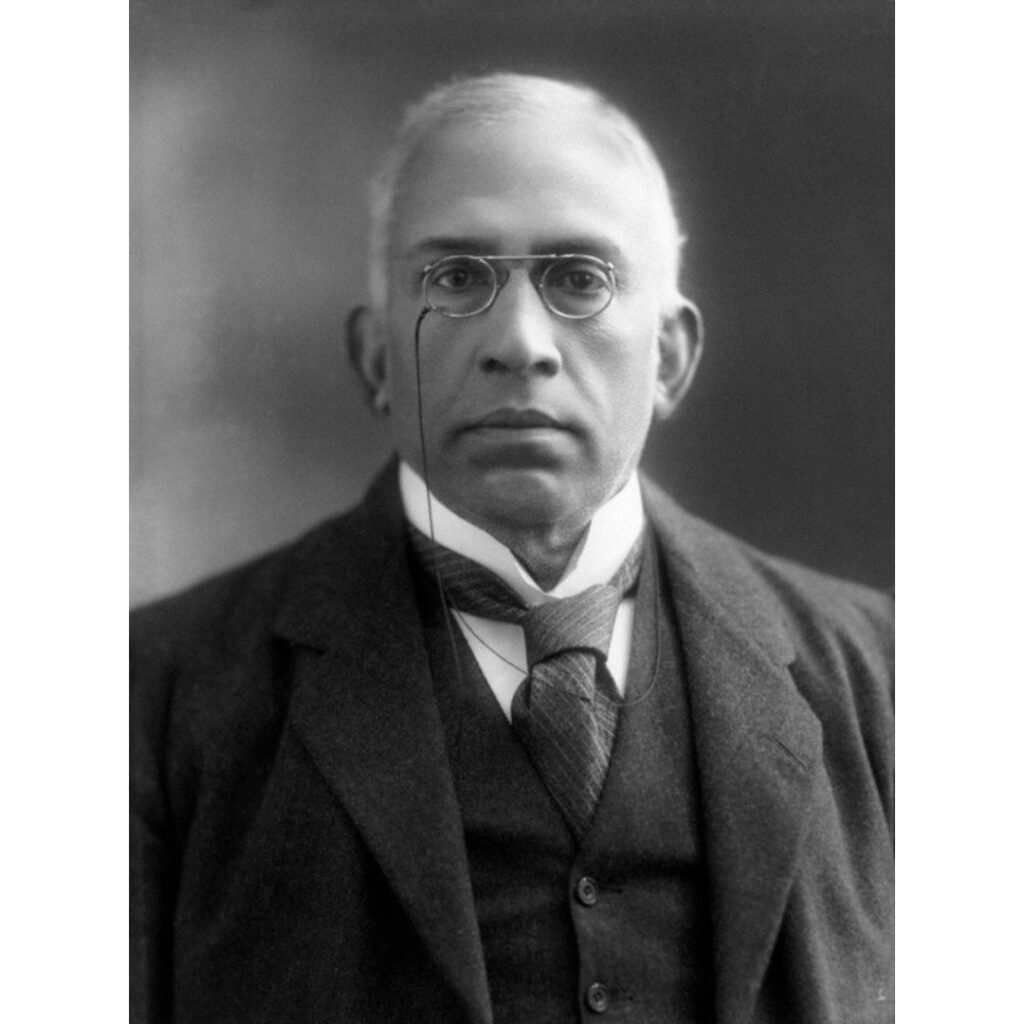

Who was Chettur Sankaran Nair?

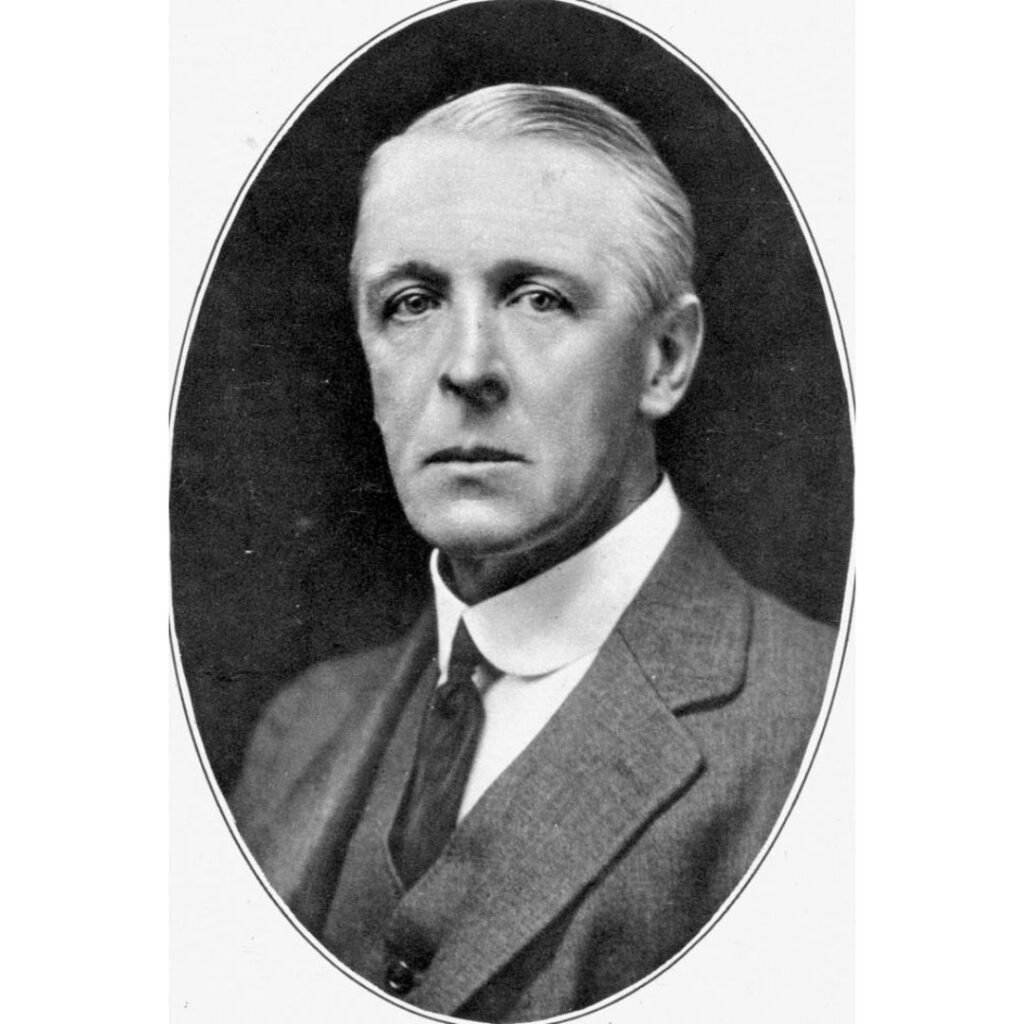

Nair was an extraordinary man. Born in Palghat district, he had migrated to Madras (now Chennai) to study law. He became a famous lawyer, then an advocate-general and finally a judge of the Madras High Court in 1908. He was one of the founder editors of the Madras Law Journal, which is the oldest legal journal in India today. He was a reformist who took progressive stands on gender-equality, caste-discrimination, child-marriage, free primary education and other important issues. Even the British respected his integrity and intellect and knighted him in 1912. In 1915, he was elevated to the Viceroy’s Council. At the Council, he courageously expressed contrarian views and even the British often turned around to his viewpoint. Nair was also a staunch nationalist. He became a Member of the Legislative Council of Madras in 1890 and presided over the Indian National Congress conference in 1897. Chettur had admirers among both Indian nationalists and British imperialists.

Nair was holding the highest post an Indian could, and he wanted to quit. Motilal Nehru and other nationalists urged him not to resign, but to work within the system and influence the British to do the right thing. Much to his disappointment, Lord Chelmsford’s government did not even acknowledge that it had done anything wrong. After holding on for three months, Nair could no longer tolerate the situation and resigned in July 1919.

Nair had just rejected a job that only a few Indians could aspire for at that time. Was he not ruining his career and plunging into obscurity? For him, personal consequences were immaterial! Ironically, this was the beginning of a glorious chapter in his life: according to his biographer, KPS Menon, “his star was never brighter”. But had he not thrown away a chance to correct the wrongs of Jallianwala Bagh? Unexpectedly, his resignation did have an impact. It galvanised the British into appointing the Hunter Commission, consisting of both Indian and British members, to enquire into the massacre. Dyer and O’Dwyer had claimed that they had crushed a rebellion but the commission ruled that “ there was no rebellion that required to be crushed”. Even Winston Churchill, a die-hard imperialist, acknowledged that the duo had made a complete mess.

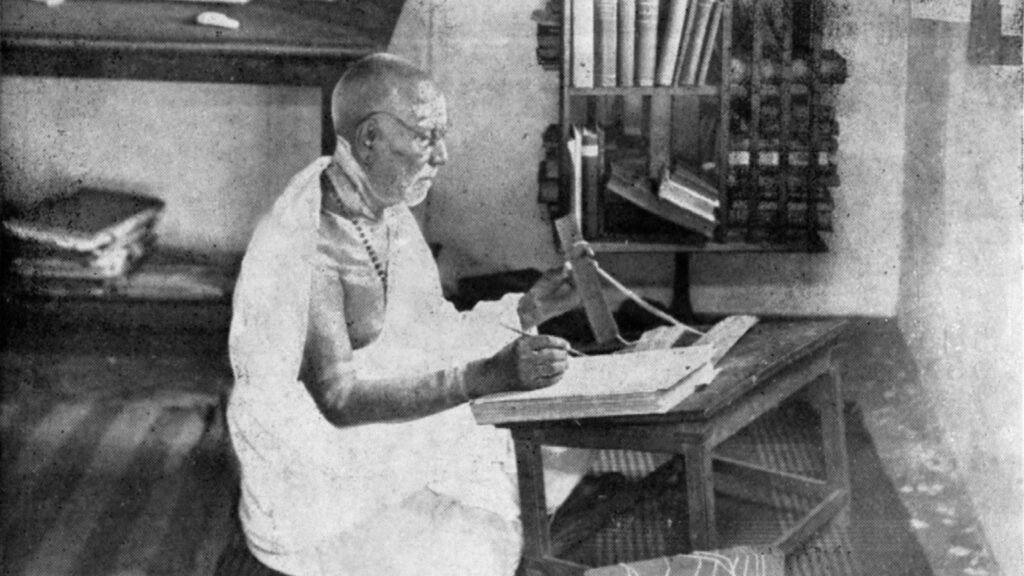

Nair returned to Madras and was given a tumultuous welcome. He decided to devote his time to writing, and wrote a book titled “Gandhi and Anarchy”. At one level, it was a critique of Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement. In Nair’s view, Gandhi was experimenting with an unconstitutional method which would one day create disorder and violence in society. Political and social reform had to be won through legal, constitutional means. Not many in the nationalist camp agreed with him, but Nair was not writing to please anyone!

At another level the book severely reprimanded O’Dwyer’s abuse of powers in Punjab. Now O’Dwyer claimed that Chettur’s book had tarnished his reputation and sued him in 1923. In reality O’Dwyer had no reputation to protect after the Hunter Commission had exposed his truth. It was just O’Dwyer’s face-saving tactic. Unfortunately, the case was posted at King’s Court London, where Nair could hardly expect neutral jurors. Eleven out of the twelve jurors voted in favour of O’Dwyer with only one juror, Harold Laski the political economist dissenting. From Nair’s viewpoint, even that was a moral victory. Since the jury was NOT unanimous, Nair was offered another trial. He declined, saying that another jury of “twelve different English shopkeepers” would not decide differently. Then he was offered a different option. He could either apologise or pay a fine of GBP 7500 (approximately GBP 586,000 or Rs. 59.5 million in today’s rates). That was a huge sum, especially for an Indian then, but Chettur chose to pay rather than bow to someone like O’Dwyer. Nair was asked by the British press: had the verdict damaged his reputation? Nair replied that even if all the judges of the King’s Court got together and unanimously declared him guilty, it would not hurt his reputation one bit!

Nair lost his case but it was a victory for his cause. During the five weeks of the hearing, the whole world got to know about the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. The British repealed the press curbs and martial law in Punjab. And now Britain was now under moral pressure to treat Indians better and give them more powers of self-governance.

Back in Madras, Nair continued to be consulted by both nationalists and the British administrators. He died peacefully in 1934. Many have forgotten him, but there are some reminders of his illustrious life. One is the Chettur Sankaran Nair Foundation, established by his family to promote social/cultural welfare. And the other is the more visible piece. There is a 30-feet-lamp (a deepastambham) with 300 wicks at the entrance of the Guruvayoor temple. That was donated by Chettur Sankaran Nair himself.

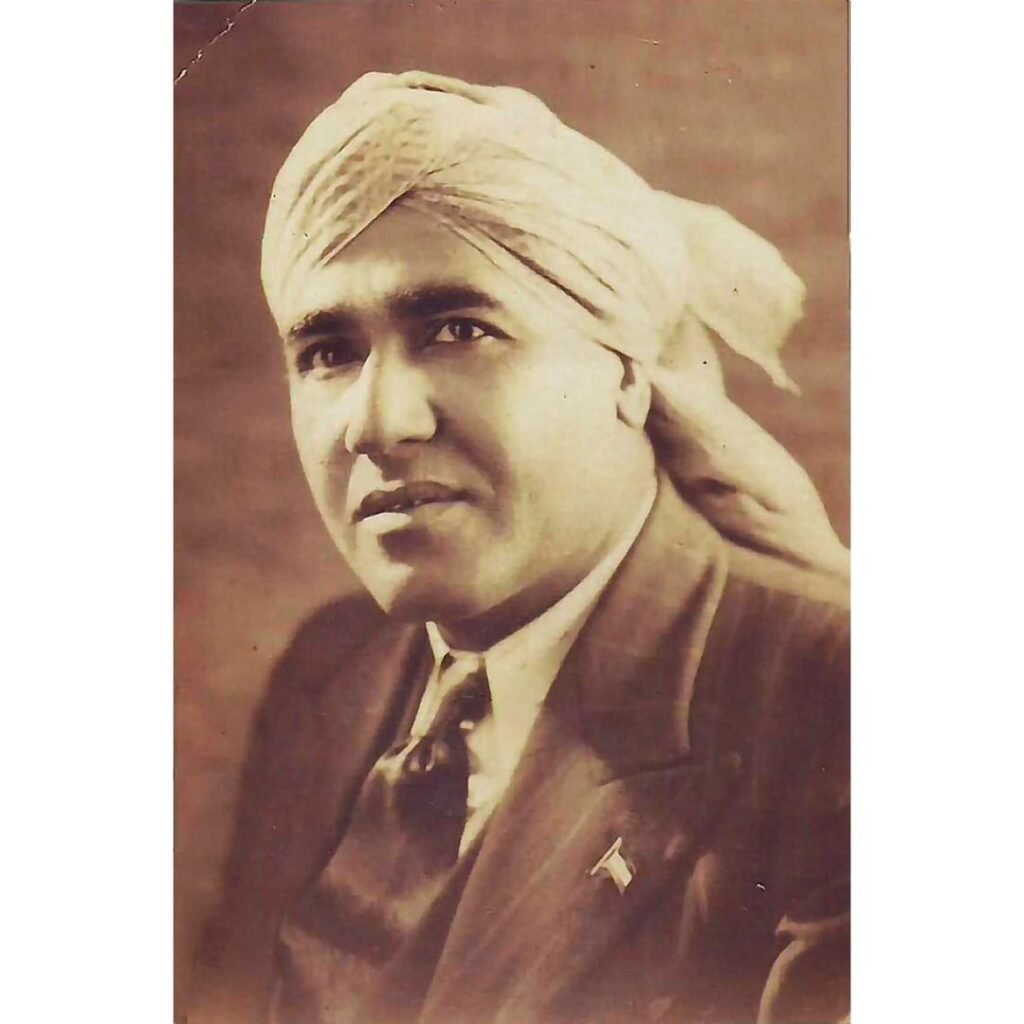

Sardar Udham Singh

What happened to the two villains of Jallianwala Bagh? Both men were relieved of their posts soon after the truth became evident. Initially they won some sympathy but that faded away.

Brig. Dyer had a brief moment of glory when a racist women’s committee presented a sword of honour to him as the ‘saviour of Punjab’ . But public opinion soon turned against him. He lived a secluded life until he had a series of strokes that debilitated him. He died a sick man in 1927.

O’Dwyer fared better. In 1925 he wrote a book justifying his actions as anti-terrorism measures in India. He kept writing columns in the Times newspaper condemning Gandhi and extolling British rule. Then, his nemesis caught up with him. A young Indian man named Udham Singh had been wounded in the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. For 20 years he diligently plotted revenge. Finally in 1940 he travelled to London and shot O’Dwyer at a public meeting, killing him instantly. Udham Singh made no attempt to escape. He calmly declared, “It was my duty (to kill O’Dwyer ). What greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?”