A mighty emperor invades a smaller kingdom. The smaller kingdom puts up an unexpectedly long and stiff resistance. Eventually, the invading emperor wins, but his war has wiped out huge sections of the populace. Filled with remorse, he converts to Buddhism and promotes non-violence for the rest of his life.

This emperor, as you might have guessed, was Ashoka. However, his life story was far more complex than this simple chain of events – something that historians debate about even now.

How do we know about Emperor Ashoka?

Ashoka was the greatest ruler of the Mauryan Empire, who ruled during 268-232 BCE. The Mauryan Empire was at its peak then, covering most of India (except Tamil Nadu and Kerala), the entire regions of present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, and parts of Nepal, Afghanistan and Iran: an area exceeding 4 million square kms! Yet, early scholars knew little about Ashoka because not enough information had been unearthed. Chronicles like the Sanskrit Ashokavadana (2nd century CE), the Sinhala Mahavamsa (3rd – 4th century CE) and the Chinese travelogues of Faxian (5th century CE) and Xuanzang (7th century CE) were written long after Ashoka’s death, so a number of conflicts and biases had crept into these narratives.

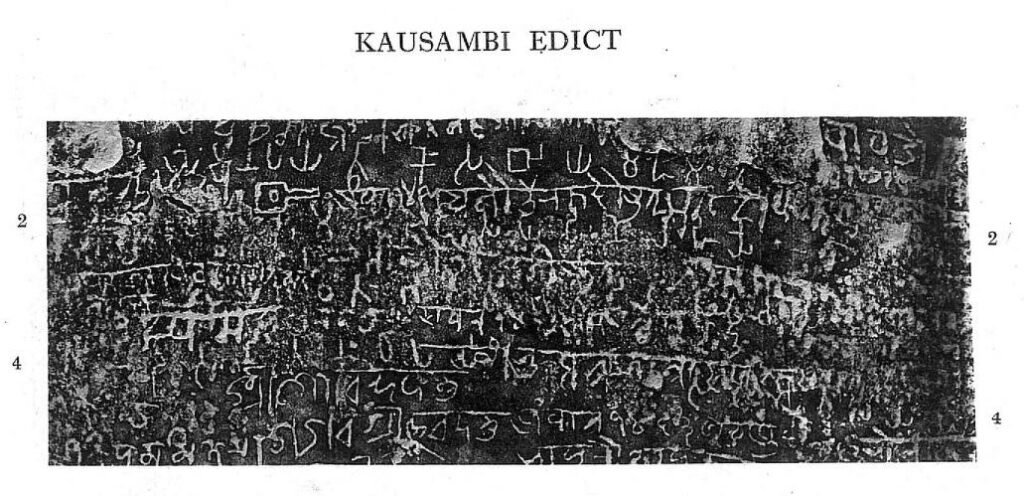

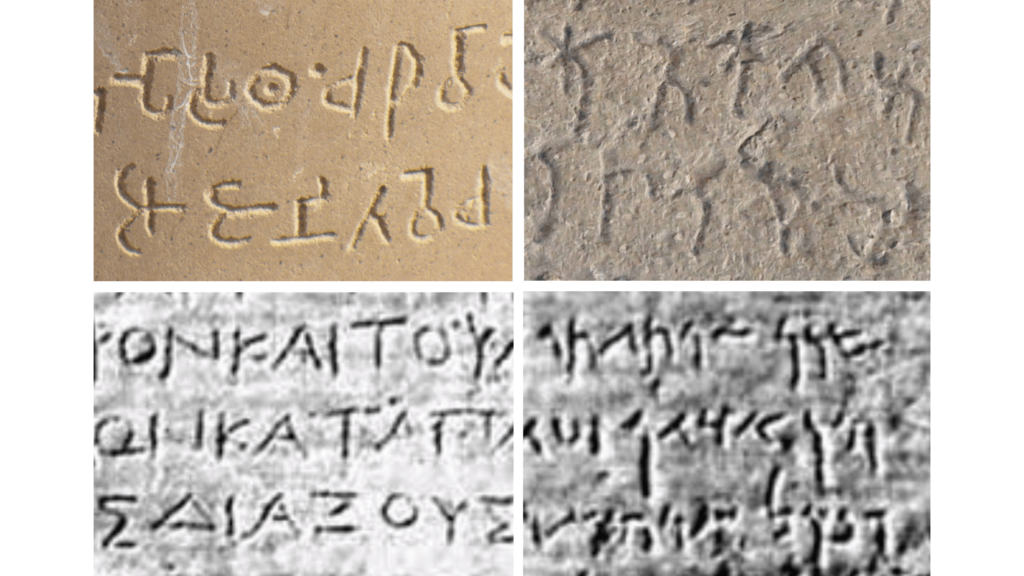

Then in 1837, a British epigraphist named James Prinsep deciphered the Ashokan Edicts, a collection of rock and pillar inscriptions commissioned by Ashoka himself. This helped historians to finally reconstruct Ashoka’s life story.

Detour: You can watch the story of the decoding of the Brahmi script by Prinsep in this video :

The Brahmi script: Decoding ancient Indian history | James Prinsep

Ashoka’s rise to power

Before we talk about the Ashokan Edicts, let us take a look at the times in which the emperor lived. Ashoka’s grandfather, Chandragupta overthrew the powerful Nanda kings, overcame the Greeks and then created a vast empire in northern India. An era of enormous economic prosperity began. Chandragupta’s son Bindusara – Ashoka’s father – continued the momentum and the Mauryan Empire had become the first great pan-Indian state.

Where did Ashoka fit in? According to one version, Bindusara had 16 wives and 101 sons by them. Ashoka’s mother, Shubhadrangi, was not a princess, but a poor Brahmin elevated to royal status. Bindusara had no special love for Ashoka, although he recognised him as a competent and courageous leader. Ashoka was therefore allotted tough assignments, like crushing a rebellion in Takshashila, and the governorship of Ujjain. The heir-apparent however, was Crown Prince Susima, Ashoka’s stepbrother. But when Bindusara fell seriously ill, Ashoka rushed to the capital before Susima, seized the throne and had Susima assassinated. He executed all his stepbrothers and spared only his womb-brother. The stakes for the empire were so high that only a ruthless person could succeed. Ashoka was just that!

His early reign was marked by high-handed cruelty. He beheaded 500 courtiers (they were probably loyalists of the old regime or had exceeded their brief), and is believed to have got a special prison constructed – the legendary Ashoka’s Hell – where dissenters were tortured and killed.

By 261 BCE Ashoka had firmly established control over the empire. He now decided to conquer Kalinga (modern Odisha), a wealthy, prosperous kingdom that had sea ports and was a strategic bridge to the southern kingdoms. His father and grandfather had failed to conquer it, but Ashoka was not going to miss the opportunity. Unfortunately, he underestimated the Kalingas, who repulsed all his initial attacks. Ashoka finally defeated them but at a massive cost. About 100,000 enemy soldiers were killed and about 150,000 imprisoned or deported. The Mauryan casualties were heavy too.

The Ashokan Edicts

According to popular belief, the carnage shocked Ashoka so much that he never waged war again, and became an ardent advocate of non-violence. He built stupas across India. He commissioned inscriptions on rocks, pillars and caves promoting his ideals of peace all over the country. That is how the Ashokan Edicts came to be. An extract from Major Rock Edict XIII says it all:

“This is the repentance of Devanampriya (Ashoka) on account of his conquest of (the country of) the Kalingyas. For, this is considered very painful and deplorable by Devanampriya, that, while one is conquering an unconquered (country), slaughter, death, and deportation of people (are taking place) there.” (Translation by E Hultzsch).

He also began a campaign of “conquest by morality” sending evangelists of Buddhist tenets to southeast Asia and as far west as Greece.

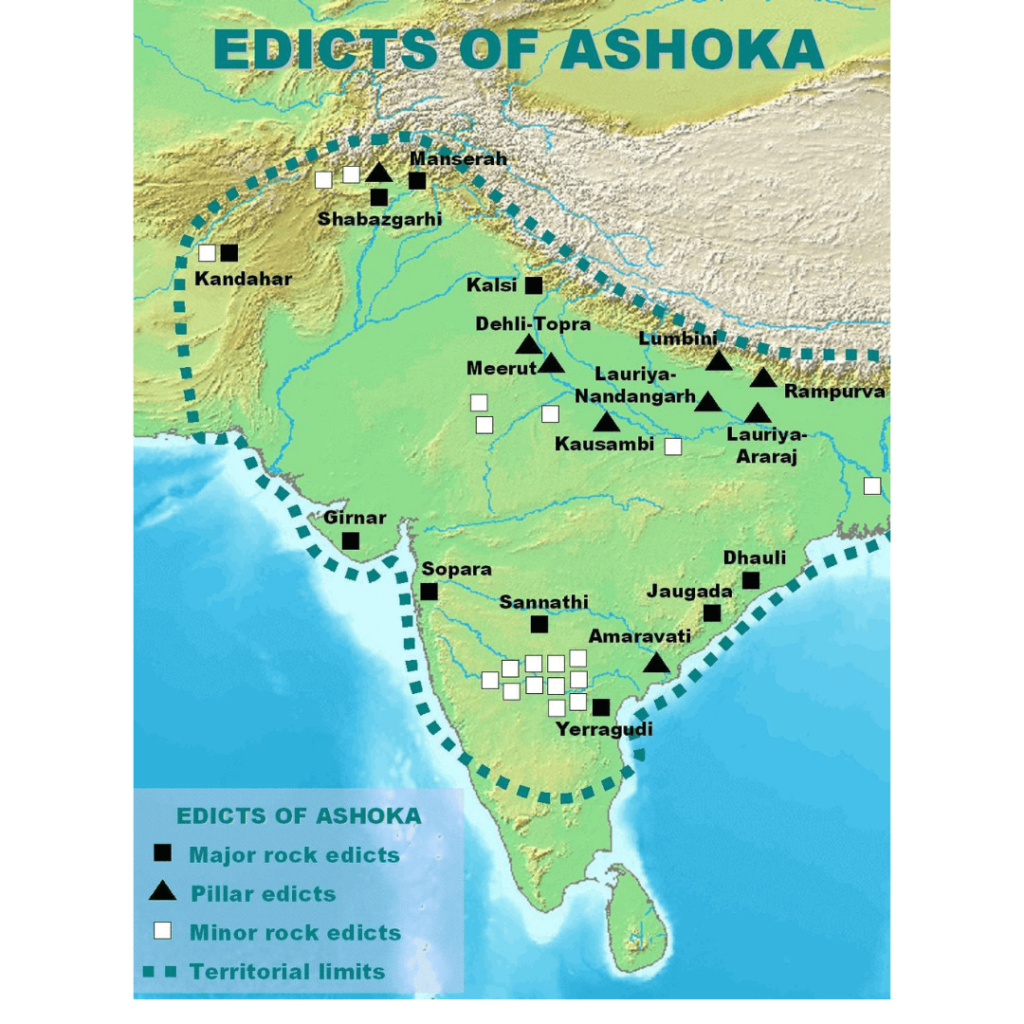

It is possible that thousands of such edicts were carved all over the country, but only 33 have been discovered so far, in places from Afghanistan to Andhra Pradesh. They are in three languages – Prakrit (in Brahmi or Kharosthi script), Greek and Aramaic. Interestingly, Greek and Aramaic were understood in the north-west Mauryan Empire, and Ashoka was reaching out to his subjects in those parts. Archaeologists have classified the Ashokan Edicts into the following categories:

- Major Rock Edicts (14)

- Minor Rock Edicts (7)

- Major Pillar Edicts (7)

- Minor Pillar Edicts(5)

The Minor Edicts deal more with the principles and practice of Buddhism. The Major Rock Edicts are longer and rather secular. They deal mainly with governance, and the duties of the citizen in terms of maintaining a peaceful, non-violent society.

Why did Ashoka commission the edicts?

Why did Ashoka commission so many edicts with very similar messages? Governments today issue press releases announcing public policy, and these are circulated through newspapers and digital media. But Ashoka was running a country larger than modern India, at a time when communication and transport were primitive. So, he used contemporary media – walls and pillars! He was smart enough to publish them in languages and scripts that the locals were familiar with, at public places where they could be read by all; perhaps someone would even read them aloud for the illiterate. Nobody could claim ignorance of the rules.

The transformation of Ashoka

But how did a cruel despot suddenly transform into a benign patriarch? Some historians consider the accounts of pre-conversion cruelties to be gross exaggerations. It is possible that overzealous propagandists wanted people to believe that Buddhism had miraculously transformed Ashoka. Many historians suggest that although the Kalinga war might have had a huge impact, it was merely the final trigger in a gradual transformation. There is evidence that Ashoka was a Buddhist long before the Kalinga war. When Ashoka was still the governor of Ujjain, he married Devi, the daughter of a rich Buddhist merchant, who was a significant influence in his life. Thus, the thought process could have started long before he even ascended the throne.

If he was a non-violent Buddhist already, why murder his brothers? Why start a war? Well, it is fine to work towards an ideology, but one also has to face political realities. In order to enforce his philosophy, he had to capture power first – by whatever means possible. And as an astute king, he could not be blind to the strategic possibilities of Kalinga. Absolute non-violence was impossible, so he chose a middle path of using “some” force. When he assumed complete control, the violence became redundant.

Well, almost. There is evidence that he used violence even after his conversion to Buddhism. Ashoka ruled over a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious society. While Vedic Hinduism was the majority religion, there were other faiths like Buddhism and Jainism, and there were influential fringe practitioners like Ajivikas and Charvakas too. Although they usually coexisted in peace, some friction was inevitable, and Ashoka was not above using force to restore order. There were two instances where artists belonging to Nigrantha and Ajivika sects had drawn pictures demeaning Buddha. Ashoka ordered about 18,000 followers of these sects to be executed. Now he may have overreacted or the numbers may be exaggerated, but it is not improbable that he used violent force.

What kind of a man was Ashoka?

How do we assess Ashoka? Undoubtedly a ruthless man, he could not have captured the throne and held together such a vast country without, perhaps, being so hard-hearted. He was also an idealist who dreamt of a peace-loving non-violent state. The Ashokan Edicts are clear proof of that. But he was practical enough to understand that sometimes peace had to be achieved by show of force. Above all, he was a pioneering media guru. The rocks and pillars he invested in over 2000 years ago are still promoting Brand Ashoka!