Most schoolchildren know the story of Lakshmibai, the queen of Jhansi who died fighting British colonialism in India in the 1800s. But only a few have heard of Rani Abbakka Chowta who died fighting the Portuguese three centuries earlier! Rani Abbakka lived in a volatile era and data about her life is sketchy and incomplete. Yet, it is a story that needs to be told.

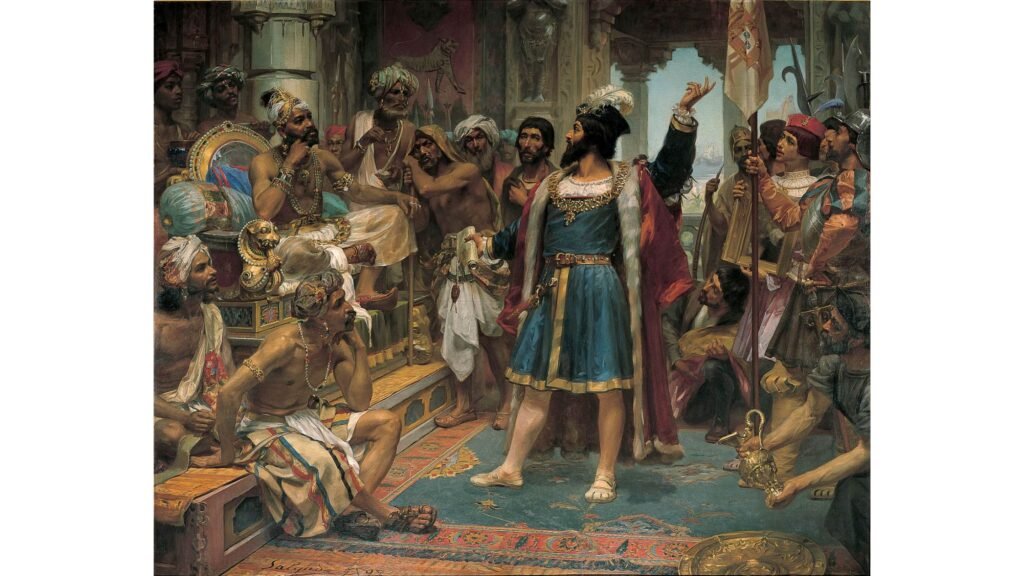

The Portuguese adventurer Vasco da Gama arrived in Kerala in 1498, ostensibly for trade. But by 1505, Kochi had become a satellite state of the Portuguese and by 1510, Goa was a full-fledged Portuguese colony. It was clear now that the Portuguese wanted to colonise and not just trade in India. Krishna Deva Raya, the Tuluva king of the Vijayanagara empire was a major deterrent to Portuguese territorial ambitions. Unfortunately, he died in 1529 and the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire began.

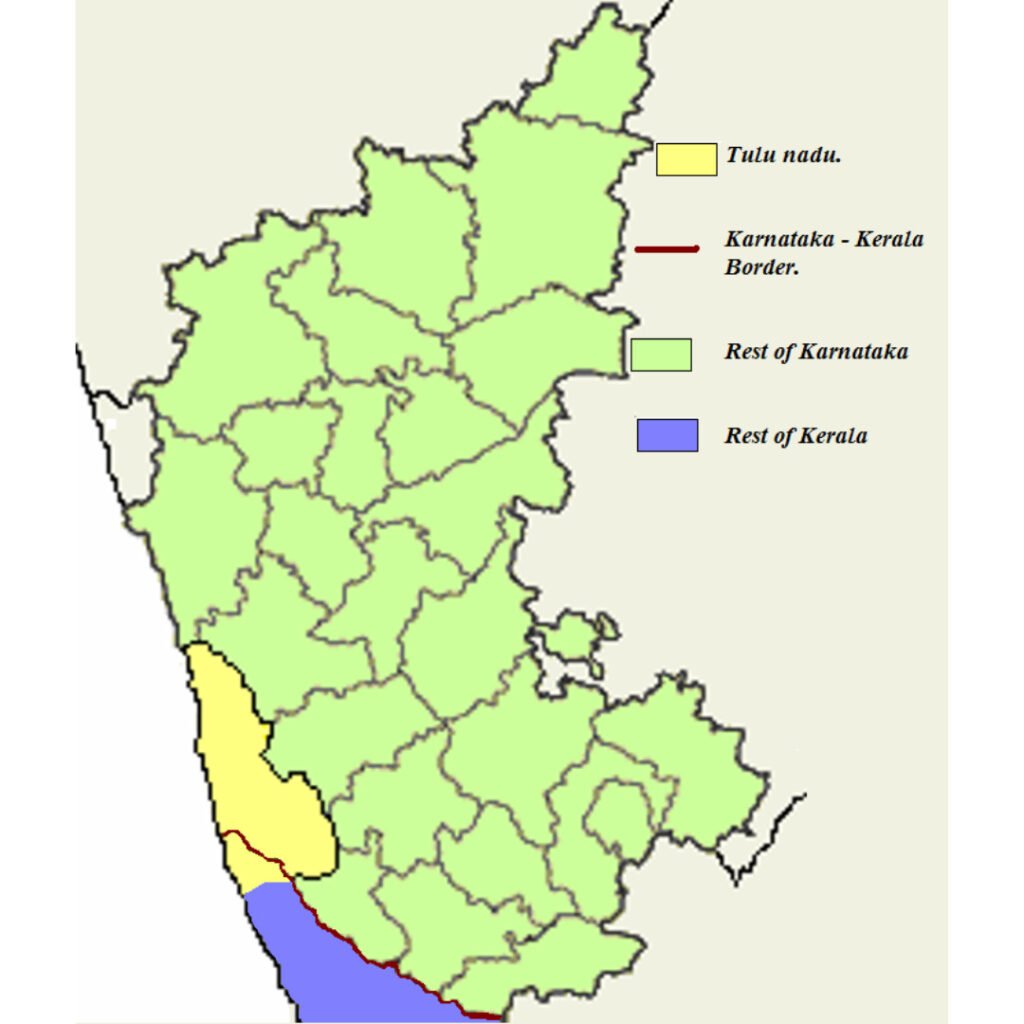

The Udupi-Dakshina Kannada-Kasaragod region known as Tulu Nadu was a valuable commercial territory, because a lot of pepper and spice trade passed through it. It was a collection of principalities governed by different Tuluva kings who ruled as feudatories of the Vijayanagara emperor. The decline of the Vijayanagara empire meant that they became substantially more autonomous, but the downside was that they also became more vulnerable to Portuguese hegemony. This is where Rani Abbakka Chowta’s story begins.

Abbakka’s ancestors were Jain royals from Gujarat, who probably migrated to Karnataka’s Tulu Nadu region around the 12th century. Having settled in Ullal (a port town near Mangalore), they became completely naturalised citizens, adopting the local language and customs as their own. Although they were Jains, they adopted the Hindu god Somanatheshwara of the nearby Someshwar temple as their family deity. And, like the Tuluva warrior class, they followed a matrilineal system called Aliyasantana. This was similar to the Marumakkathayam matrilineal system followed by the Nairs of neighbouring Kerala. In this system, property passed on from mother to daughter (not father to son).

Detour: Watch this short video to find out more about Kerala’s matrilineal system.

Under Aliyasantana, the son would get a very limited share but help the daughter in managing the inherited property. This system evolved in martial communities where most of the menfolk were busy in wars, and so women had a more important role in managing the family. This was also applicable when the inheritance in question was the kingdom itself. The prince who inherited the kingdom was not the king’s son but his nephew (because the property belonged to the king’s sister now!). What if the king had no nephew? The niece could become the queen in her own right. This is what happened in Abbakka’s case.

Abbakka’s uncle Thirumala Raya ruled Ullal during 1510–1544. He had no nephews and so he trained Abbakka in martial arts and state-craft. While it was not common to have a female head of state, it was certainly not unique.* Thirumala got her married to Lakshmappa Arasa (aka Lakkarasa), the Banga king of the neighbouring Mangalore kingdom. The marriage was a strategic alliance during difficult times. In 1544, Abbakka succeeded Thirumala Raya as monarch of Ullal. She stayed at Ullal and raised her children. (Historians have different opinions on why she stayed apart. Was she estranged, or did she follow an Aliyasantana custom of bringing up children in her native home?)

At this time Indian spices, especially pepper, were highly valued in the European markets. The international spice trade was dominated by the Arabs by virtue of their India connection. When the Portuguese entered India, they tried to brow-beat and arm-twist Indian kings into signing monopsonic contracts with them and break the business relationship that they had with the Arabs and Persians. The Portuguese navy was a glorified pirate fleet which harassed Indian shipping. Using their considerable sea-power they bullied kingdoms on the Indian west coast to pay ‘kappa’ (protection money ). One by one, many kings succumbed to the pressure, but a few resisted. The most powerful resistor was the Zamorin, the king of Calicut. Some small kingdoms like Abbakka’s Ullal held out too. Abbakka found a natural ally in the Zamorins. Yet, she knew that sooner or later, an armed confrontation would happen.

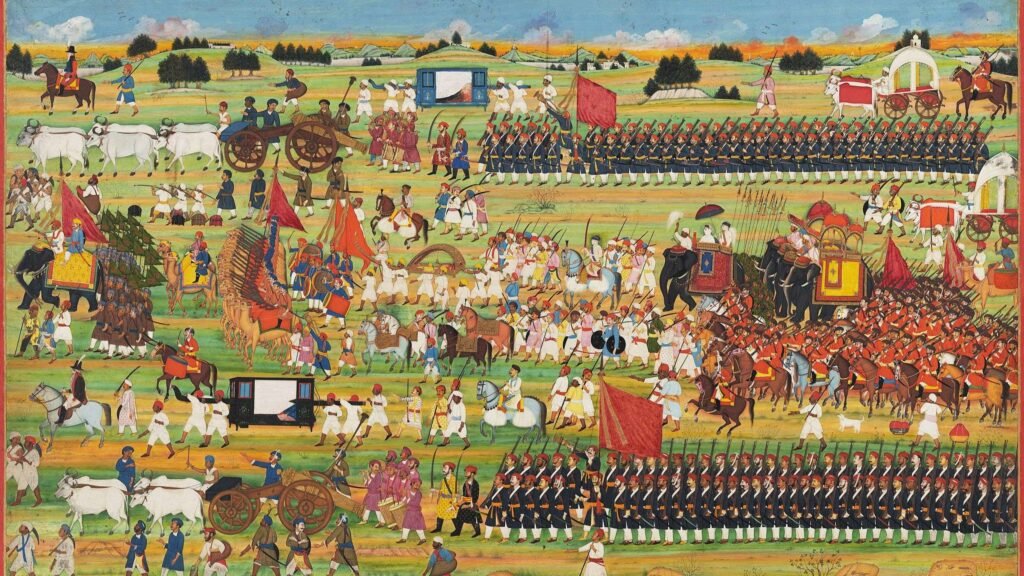

Abbakka was well prepared when the Portuguese commander Dom Alvaro de Silveira attacked Ullal in 1556. The Portuguese could not break in, but Abbakka could not break them either, and so a temporary truce was agreed. In 1558, the Portuguese attacked again with a larger army under Louis DeMello. This time they caused considerable damage to Ullal. But timely help came from some natural allies – the Moplahs of Malabar (settlers of Arab or Persian descent in Kerala) and the Zamorin of Calicut himself. This was too much for the Portuguese force, which retreated.

Throughout the war, Abbakka’s husband, the Mangalore king, did not help at all.† Anyway, peace returned to Ullal for the next few years and Abbakka boosted the economy by improving irrigation and trade. Ullal was once more a big spice exporter. This obviously did not go well with the Portuguese plans. Around 1568, the Portuguese attacked with a surprisingly large force under General Joao Peixoto and ransacked Ullal. Abbakka escaped and hid in a mosque.

Unfazed, she immediately gathered a guerrilla force of 200, attacked the Portuguese camp and killed Peixoto and forced the Portuguese to retreat. This was followed soon by guerrilla attacks on the Mangalore fort where the Portuguese admiral Mascarenhas was killed.

But the Portuguese managed to recapture the Mangalore fort. Abbakka allied with the Bijapur Sultan and the Calicut Zamorin and continued harassing the Portuguese. Unfortunately, luck ran out for the alliance by early 1570. The Zamorin general was killed in battle and Abbakka was captured and killed. The Portuguese now had control of virtually the entire west coast trade. This was to last over a century till another western power – the Dutch – dislodged them.

Even today, performing arts like Yakshagana and Bhoota Kola celebrate Abbakka’s heroics. Folklore remembers what academia forgot!

*Between the 13th and 17th centuries five queens had ruled over Mangalore in the Banga dynasty. But the best example of a powerful queen is Rani Chennabhairadevi, queen of Gerusoppa, another Vijayanagara feudatory in Tulu Nadu. Like Abbakka, she too was a Jain. She ruled for 54 years during 1552-1606, making her probably the longest reigning Indian queen. The Portuguese called her Raina-da-Pimenta or ‘Pepper Queen’ and tried to control Gerusoppa, but she outwitted them.

†Why did Lakshmappa not come to Abbakka’s aid? The popular explanation for this is that Abbakka and Lakshmappa were already estranged. Alternatively, Lakshmappa was probably helpless because Mangalore had already succumbed to Portuguese pressure. Another credible theory is that Lakshmappa’s nephew Kamaraya conspired with the Portuguese to seize the Mangalore throne. Kamaraya came to power by 1556, so Lakshmappa’s role had become irrelevant then. We need further evidence for a definitive answer.

PS. How did Abbakka, a follower of Jainism which advocates extreme non-violence, lead an army? Throughout history we find examples of Jain kings heading powerful armies, like Mahendra Varma Pallavan, Arikesari Parankusa Maravarma Pandyan, Bindusara Maurya, and so on. The Jains outrightly condemned killing due to greed and hatred. But they were practical enough to accept carrying arms to protect citizens. To this day there are many Jains in Indian armed and security forces.