In 2005, a farmer was ploughing his fields in Sanauli in western UP when he accidentally unearthed some skeletons and copper pots. After he informed the local authorities, a posse of archaeologists descended on the sleepy village and stayed on for 13 months! And they have been enthusiastic about Sanauli since then. Why this ghoulish glee over a gloomy graveyard? Therein lies our story.

They say ‘dead men tell no tales’; but in the hands of skilled archaeologists, they can write volumes of history. You see, archaeologists capitalise on the long-held human belief that life does not ‘end’ with death. Of all the species on Earth, humans have been the most successful survivors; yet, they cannot accept that after years of successfully negotiating life, death causes an abrupt end. Century after century, civilisation after civilisation, humans have nurtured vivid beliefs of an after-life. Heaven, hell, Hades, Valhalla, rebirth, purgatory…are all part of this. And rituals relating to the after-life are a great reflection of the realities that prevailed pre-death. So, ancient graveyards provide many clues about life in ancient civilisations. While many monuments above the surface have vanished due to natural and manmade causes, graveyards have preserved historic artefacts safely under layers of earth.

In ancient Egypt for example, the magnificent pyramids were really graves for the elite. Egyptians believed that a dead person would pass through the underworld to be judged whether they had been virtuous; if they had been virtuous, they would reach the Field of Reeds – a kind of heavenly version of Earth, and live happily with their spouse, children, pets and even the same set of servants!

Since the Field of Reeds was similar to Earth, it was assumed that the dead person would need their earthly body – and hence the body was mummified for burial. The burial chamber was filled with gold, jewels, and all other good things they had on earth, since they would be using them after-life anyway. The things they buried along with the dead king or queen were called ‘grave goods’ for obvious reasons. Did you know that during the First Dynasty era (c. 3000 BCE) they even interred all the dead king’s slaves and servants with him? After all, he would need their services in the after-life!

Many other societies had the practice of burying grave goods – like the Mesopotamians. They were worried that if the burial was not done correctly, the dead person would return as a ghost! The Sumerians buried food and tools along with the dead person. The Vikings too had a practice of interring the deceased with grave goods. A warrior would be buried with his weapons and saddle, a blacksmith with all his tools, and a woman with jewels and household articles. Richer folks got more grave goods, while outstanding warriors were interred with many weapons.

What about ancient Indians? Let’s go back to Sanauli. The Sanauli archaeologists intuitively knew they were onto something big: they threw every piece of technology at it! They used photogrammetry, ground penetrating radar surveys, magnetometers and drones, and it paid off. Sanauli is the largest ancient burial site to be discovered in India so far, where more than 125 bodies have been analysed. What excited them more were the grave goods. Carbon dating tests revealed that Sanauli was about 3800-4000 years old.

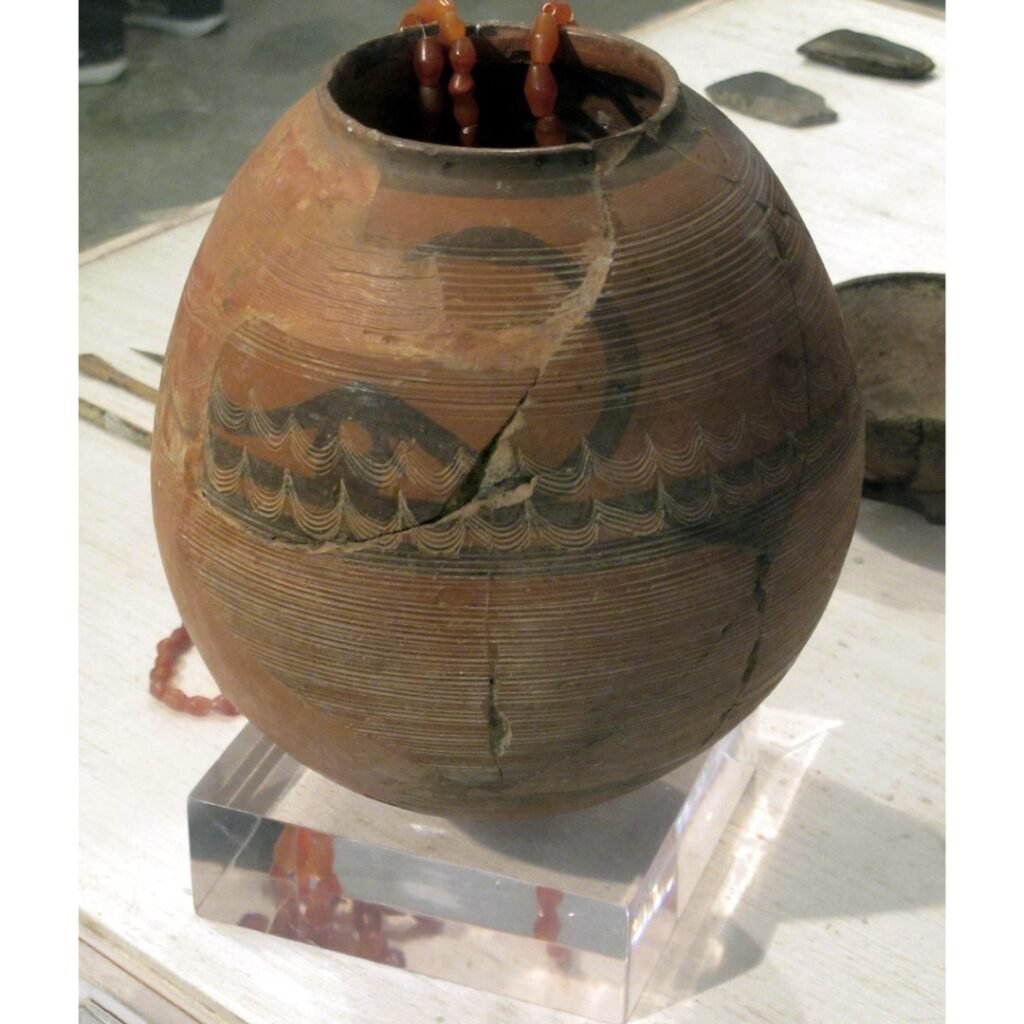

Among the grave goods were earthen vases, urns, pots, bowls, gold beads, semi-precious stones like carnelian, steatite and other items of jewellery. Initially, Sanauli appeared to be a late-Harappan or perhaps a post-Harappan site. Then they wondered: did the Sanaulians co-exist as a separate society during the same period? The bricks found in Sanauli were bigger than the standard Harappan bricks, so this was indeed possible. As they pondered over this question, they discovered some interesting grave goods. They found that many male skeletons had copper antennae swords buried by the side. These swords were considered state-of-the-art in that era. Strangely, some female skeletons too had swords and shields next to them. Stranger still, the shields were gender specific: those next to the women had steatite inlay work while the men’s shields had copper designs! Apparently the Sanaulians were a warrior tribe where women too enlisted in the army. Another interesting find was copper helmets. Some historians wonder if the so-called helmets were inverted pots; but if the helmet hypothesis is true these could be the world’s first helmets.

Among the grave goods was another surprise: chariots with solid wheels (as opposed to spoked wheels). Some archaeologists think that these could be ox-drawn carts; but after examining the size and shape, other scholars believe that they were chariots drawn by two horses with room for only two standing passengers. These vehicles are different from those found in Harappa, and resemble contemporary Mesopotamian chariots. These were probably used by warriors in battle. It has been a long held view that horses came to India after the so-called Aryan invasion. This invasion is supposed to have happened at the end of the Late Harappan era roughly after 2000 BCE. But if the Sanaulians already had horse-drawn chariots, perhaps the Aryan theory needs to be reworked. Sanauli’s grave goods have given us lots of data, but have also raised new questions. That is good, because it will inspire more research and reveal new information.

Now for another grave goods story. In Kashmir’s Srinagar district is a town called Burzahom, which has a popular cricket ground where T20 matches are played. In the 1930s, a Yale-Cambridge team unearthed prehistoric artefacts in the same playground. By the 1970s, people had forgotten all about it, but recently there has been renewed interest in Kashmiri history. Buried at different levels in this ground is evidence of human habitation from 8000 BCE. It shows the progress of the natives from a hunting to a pastoral to an agriculture community. Here was a society contemporaneous with Harappa, and a link between Central Asia and India. The possibilities are so exciting that it has been placed under the UNESCO Heritage watchlist.

The most interesting grave goods here are not materials but creatures! A rock painting shows two hunters hunting deer aided by a dog. The sky in that painting shows the sun and a supernova. Scientists believe it could be the Supernova HB9, which was visible on earth around 4600 BCE. Apparently, dogs were besties with humans even 6600 years ago. Investigators found that pet animals – like goats, sheep and dogs – were carefully buried, indicating that animals were valued. In some graves, dogs were found buried next to the owners, showing a deep familial bonding between the two. Perhaps these pets were killed and buried so that they could be united with their master in the afterlife?

Deep south, a prehistoric graveyard in Sivakalai (625 km south of Chennai) proved that there was a vibrant society in Tamil Nadu 3200 years ago. How do they know? A grain of rice from a pot in the grave goods was carbon-dated!

Watch this short video to know more about the funerary practices of ancient Tamil Nadu.