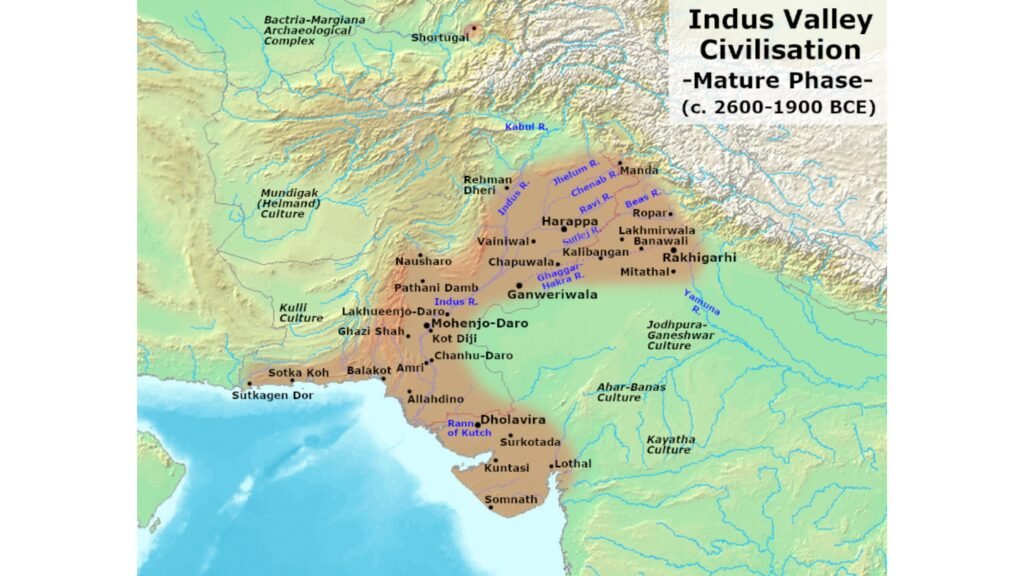

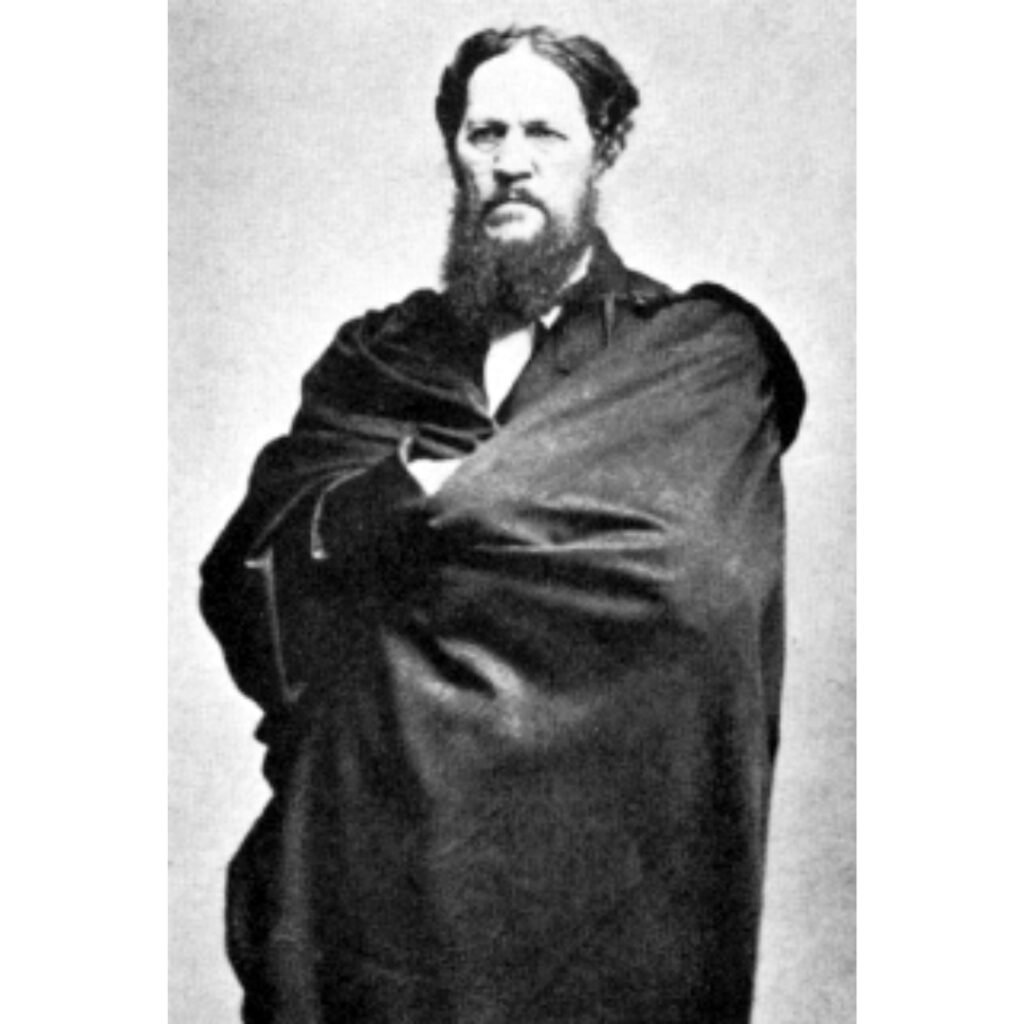

Everyone knows the Indus Valley Civilisation, one of the three oldest (along with Egypt and Mesopotamia) civilisations in the world. Between 3500 and 1300 BCE, it was a flourishing society, spread over a vast area of 1.3 million square kilometres covering western and north-western India, eastern Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is also called the Harappan Civilisation, because Harappa was where they found the first evidence of this civilisation. Who discovered Harappa? Chances are that you may not know his name. Even if you do, it is unlikely that you know his real name. This is the story of the self-taught archaeologist James Lewis, more popularly known as Charles Masson.

James Lewis led a quiet life as a clerk in a London firm, before he quarrelled with his father. And then, in a moment of frustration, he enlisted in the British Indian army of the East India Company. In 1822, he was posted in the Bengal Artillery. He saw much action in the battlefield, but he realised that his true calling was something else. When his commander involved him in the curation of his collection of zoological specimens, Lewis’s thirst for knowledge was ignited. In 1827, his regiment was posted in Agra. There he deserted the army along with a colleague, Richard Potter. This was an extreme call: in those days, the punishment for desertion was death! Lewis changed his name to Charles Masson, and Richard Potter to John Brown; the duo then travelled in a north-westerly direction to avoid detection by the British army. Thus began a long journey through east and west Punjab, Sindh, Rajasthan, Balochistan, Iran and Afghanistan.

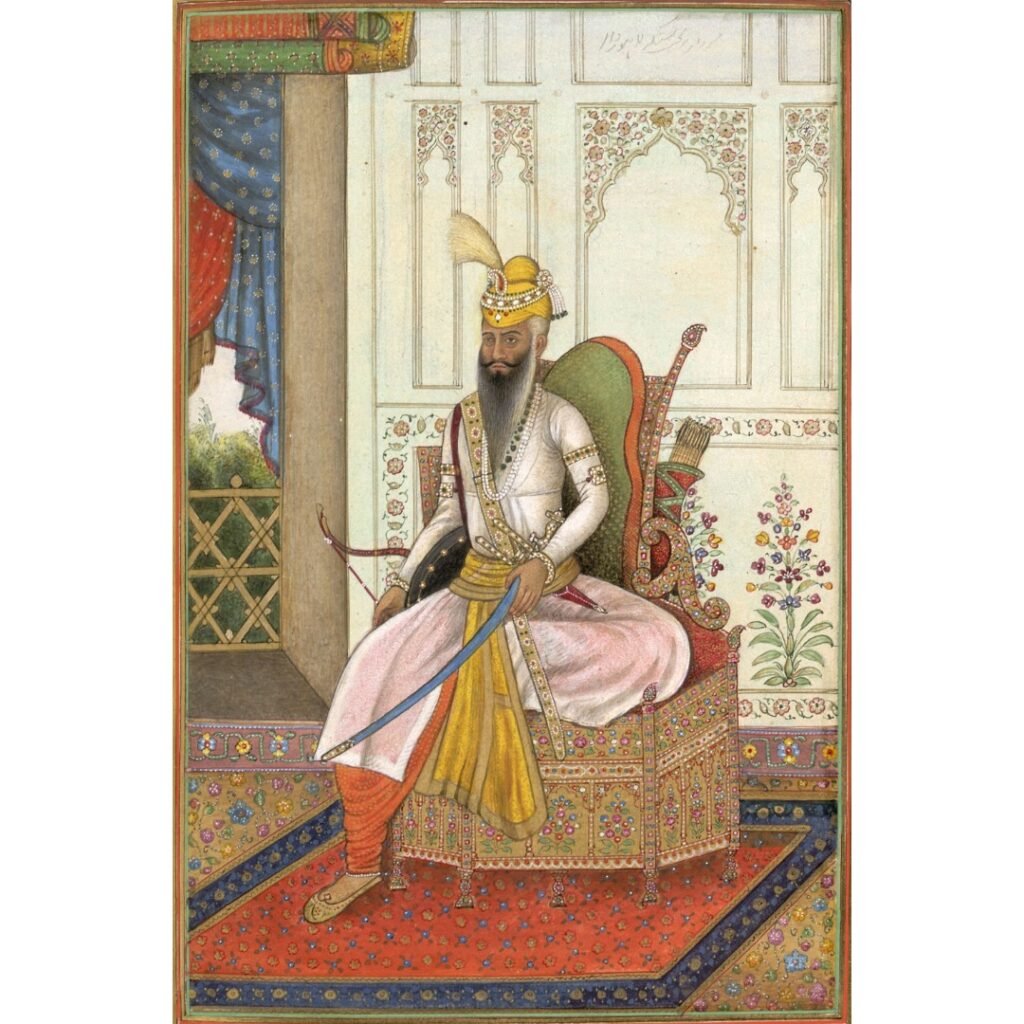

In the Punjab region, they met Josiah Harlan, an American adventurer with ambitions of ruling an Indian kingdom! Harlan had entered the court of the Punjab king Maharaja Ranjit Singh by representing himself as a doctor, soldier, scholar and statesman. His ultimate aim was to carve a kingdom for himself by playing politics between two warring royal families in Afghanistan – the Durranis and the Barakzais. (Although he never realised that ambition, he styled himself as the ‘Prince of Ghor’.) Masson and Brown told Harlan that they were American explorers going to Afghanistan, because they had to hide the fact they were deserters. The wily Harlan saw through their ruse, but he took them into his mercenary army. Masson and Brown soon realised that they had nothing in common with Harlan, and deserted his army too. This triggered a wave of desertion in Harlan’s militia and Harlan never forgave Masson. It would haunt Masson later.

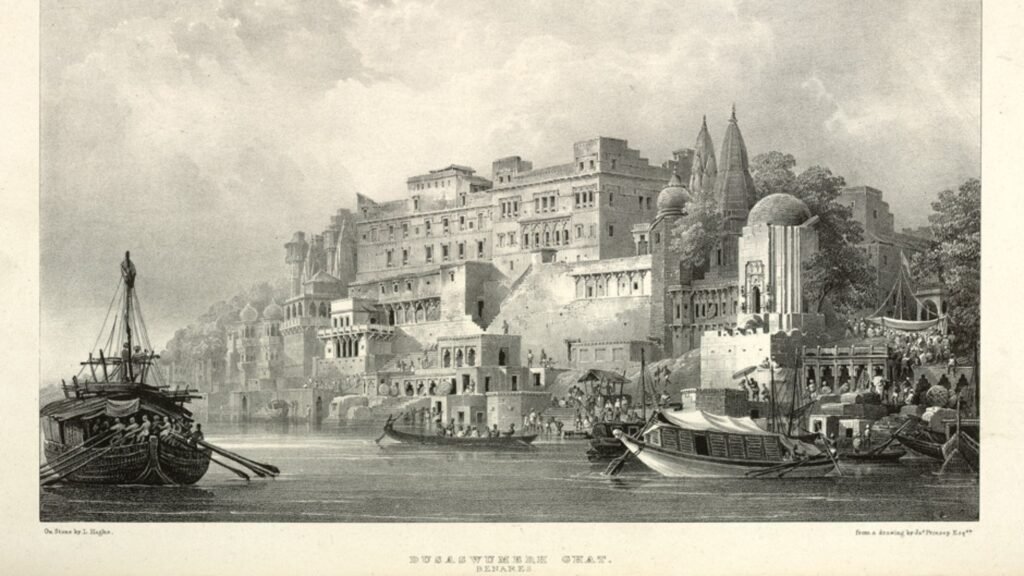

Brown joined the army of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, while Masson walked his way to Baluchistan. In the late 1820s, Masson reached Harappa (or Haripah as he called it) and was overawed by the ruins of a citadel. He realised that he had stumbled upon something great, but did not know that it belonged to the Indus Valley Civilisation. Masson did a quick investigation: he talked to the native tribesmen, made notes and sketches and moved on. Unknowingly, he became the first outsider to have discovered an Indus Valley archaeological site.

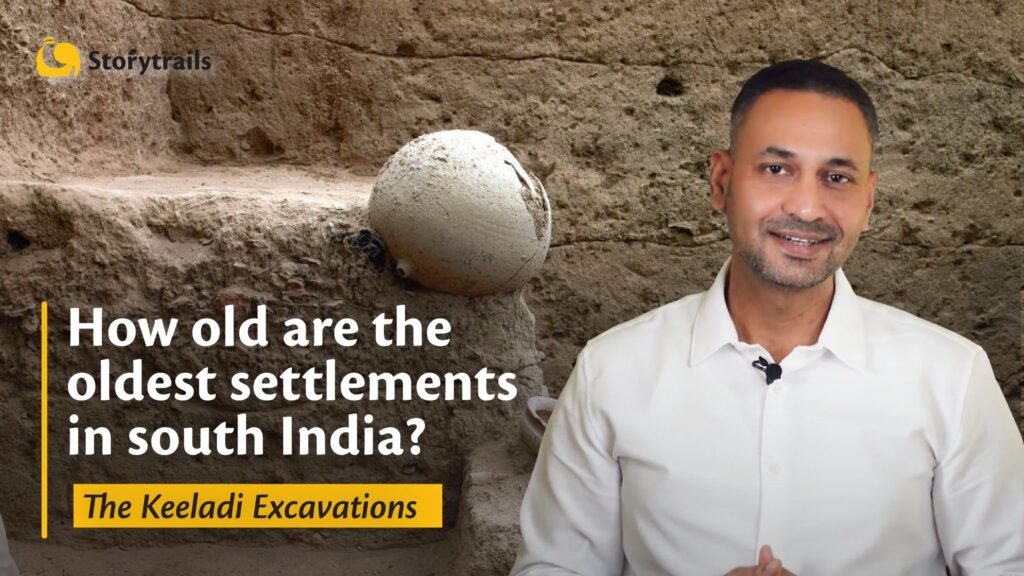

Detour: Watch this short video for the story on the Oldest Settlements in South India

He reached Afghanistan in the early 1830s and explored many sites around Kabul and Jalalabad. He seamlessly mingled with the natives, spoke their language, and immersed himself in archaeological excavations and in collecting rare coins and other historic artefacts. His knowledge of classic Greek helped him understand the Greek influences in that region. At last, he was pursuing his true calling.

Then misfortune struck. Sometime in 1836, Harlan annoyed Maharaja Ranjit Singh and became persona non grata in his court. He defected and joined Dost Mohammed, the king of Afghanistan, and arch enemy of Ranjit Singh. At Kabul he enjoyed the confidence of Dost Mohammed. Here, Harlan accidentally ran into Masson. Eager for revenge, he immediately alerted the British government about Masson’s whereabouts. It seemed like the end of Masson’s dream career, but the British authorities made an offer he could not refuse. They agreed to pardon him on the condition that he would spy on the Afghan king for the British. This was a terrible choice. If he accepted the offer, there was every chance that the king would find out and behead him; if he refused the offer, the British would execute him whenever he re-entered British territory. Masson reluctantly accepted the offer. For a few years he lived dangerously, as an archaeologist who was secretly a spy. Masson supplied valuable intelligence, although the British often lacked the judgement to act on it. By 1838 the British decided to invade Afghanistan despite the reservations mentioned in Masson’s intelligence reports. However, Masson was relieved with full pardon.

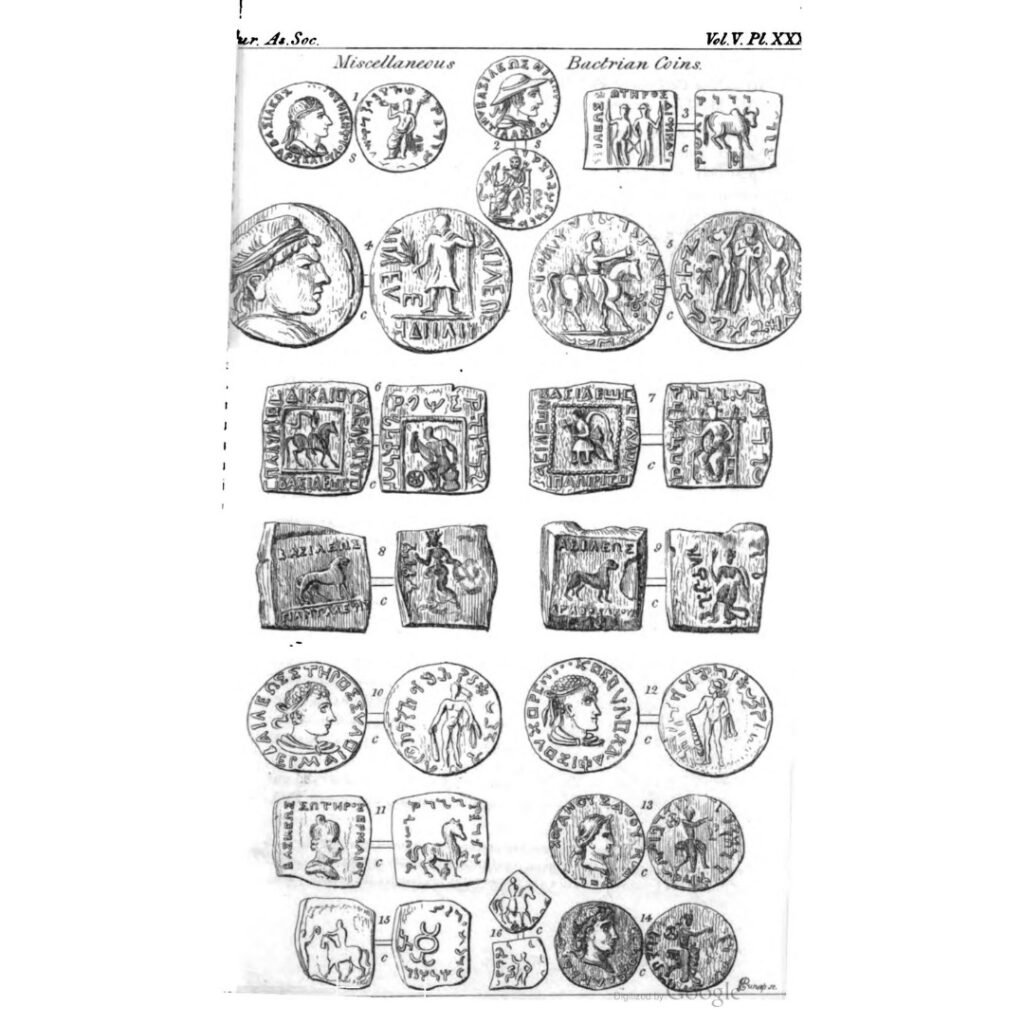

In less than 10 years Masson had made seminal contributions to archaeology in the subcontinent. He of course discovered Harappa, but the significance of that became evident only a century later. But he had achieved much more. He was an ardent numismatist – he accumulated 47000 coins, which provided the basis for understanding many hitherto unknown facts, like how the Bactrian Greek and Kushan kings once ruled Afghanistan, and that Buddhism spread to Afghanistan around the 1st century. He excavated over 50 Buddhist sites (including the now famous Bamiyan Buddhist caves 180 km from Kabul) and unearthed valuable artefacts. His near-perfect ink impression of the Shahbazgarhi rock inscription validated that Ashoka had ruled over parts of Afghanistan. His collection of bilingual coins – Greek on one side and Kharosthi – helped epigraphists like James Prinsep to crack the ancient Kharosthi script.

In 1840, Afghan rebels captured the Kalat Fort (now in Pakistan) and took Masson and the British Agent prisoners. The Afghans sent Masson to the British headquarters at Quetta to explain their demands. Instead of using Masson’s expertise, the British rashly branded Masson as an Afghan spy and imprisoned him. The Afghans promptly executed the other hostage. The British held Masson prisoner for a whole year, before realising their folly. He was released with a small pension.

Masson returned to Bombay (now Mumbai), where he spent some time surveying Elephanta and Salsette islands. He finally returned to England in 1842, and published his life’s work, but there were very few takers. He was perceived as a deserter, a discredited spy who said fanciful things. He was not from the established academia, and spoke too bluntly. Largely unrecognised, Masson died in 1853. In 1855, his collections were bought from his heirs by the East India Company for just 100 pounds. Most of the artefacts were later distributed to reputed organisations like the British Museum, Royal Asiatic Society, Victoria & Albert Museum, and so on. In 1995, the remainders – considered to be ‘mere rubbish’ – reached the British Library. When they opened the boxes, they were astonished to find that one man had achieved so much!

In 1930, a French archaeological team visited the Bamiyan Buddhist caves. They thought that they were the first Europeans to discover a specific cave above a 55-metre Buddha. To their surprise, an inscription scrawled on the wall greeted them:

If any fool this high samootch* explore,

Know Charles Masson has been here before

*Samootch = Cave

Masson went through a lifetime of hardships to pursue his passion. Sadly, true recognition came only posthumously.