Why does Makar Sankranti fall on the 14th of January (15th in leap years), while Ramzan falls on different days and even different months in a year? Why is Christmas always on the 25th of December but Easter falls any time between the 22nd of March and the 25th of April? Why is Diwali celebrated sometimes in October and sometimes in November? Is there a method to this madness? Indeed, there is!

Hindus and Christians follow the solar calendar, which happens to be about 365 ¼ days long. Muslims follow a lunar calendar with 354 or 355 days (varying over a 30-year cycle). So Ramzan occurs earlier and earlier every year in the modern calendar.

The solar calendar is based on one question: how many days does it take for the Earth to complete one revolution around the Sun? The lunar calendar is based on how long the Moon takes to complete 12 revolutions around the Earth. They both measure time, just with different reference points.

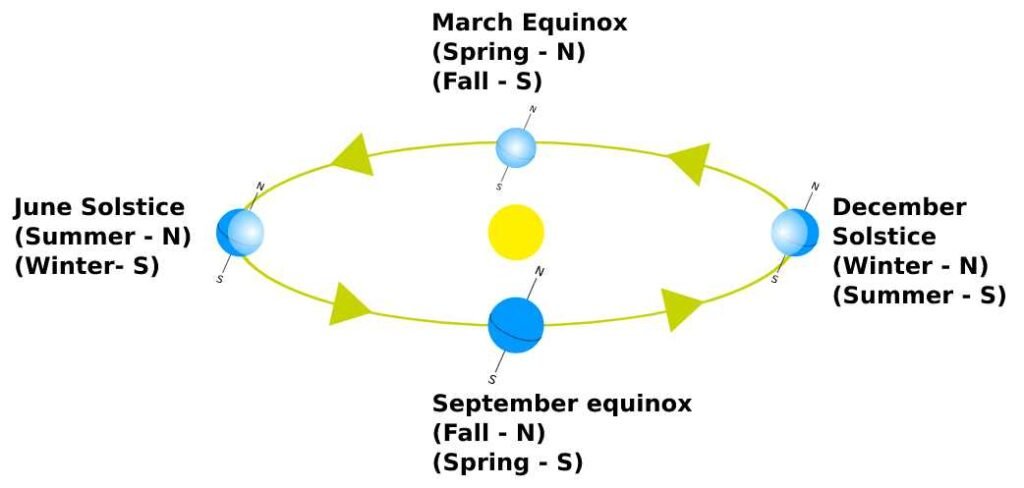

But if Hindus and Christians follow the solar calendar, why do the festivals of Diwali and Easter fall on variable dates? Here’s where it gets a little complicated. In the case of these two festivals, it’s the lunisolar calendar that’s followed. As the name suggests, it’s a mix of the solar and lunar calendars. Diwali is calculated as the first New Moon Day of the Indian month of Kartik. Easter is calculated as the first Sunday after the full moon that occurs after Spring Equinox (21st March).

Detour: Watch our short video on the Hindu calendar.

Since Indians follow the standard solar calendar, Sankranti will always be on 14th January, right? Wrong! There is nothing standard about the solar calendar. Because the Christian solar calendar looks at the Sun from a slightly different perspective from the traditional Hindu calendar.

Christians follow the calendar devised by Pope Gregory in 1582, which is also the modern secular calendar that is widely used across the world. It corrected many inaccuracies of the previous methods, and is rather simple to understand. In this calendar, one year is the time elapsed between one Winter Solstice and the next.

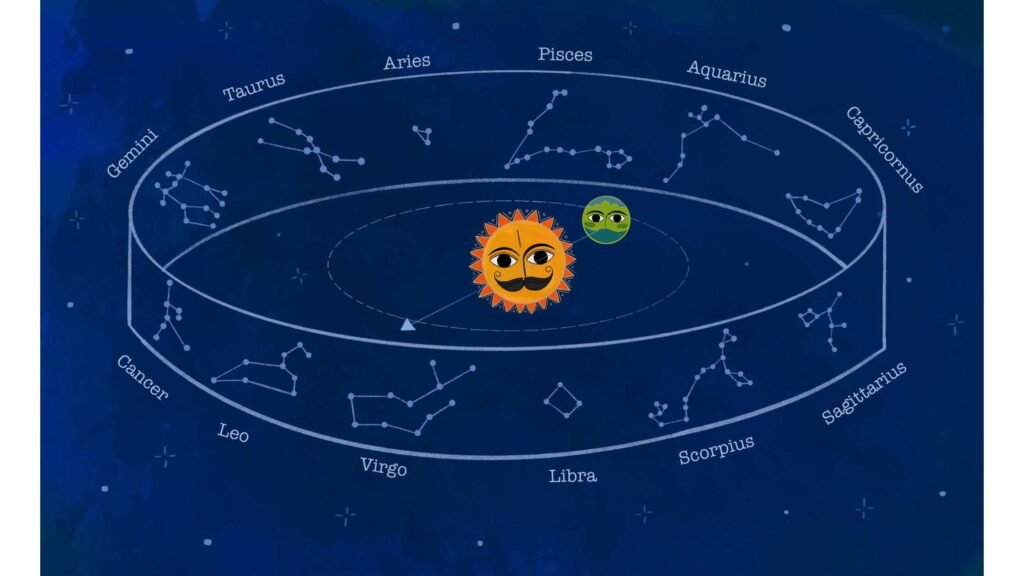

Sankranti dates are not based on this solar calendar, but on a different solar calendar. Basically, there are other ways by which you can calculate a year, using the same Sun as a reference point! In fact, Makar Sankranti means “entry of the Sun into the constellation of Makara (or Capricorn)”. Of course, the Sun does not actually enter the constellation of Capricorn, which is many light years away. It just appears so on the day of Sankranti.

Now why did the ancient Hindus adopt such a complex definition?

When you know that both the Sun and the Earth are moving independently, you need a “fixed” reference point in the sky to measure the beginning and end of a revolution. Looking up in the sky, they located 12 fixed points, the 12 zodiacal constellations (Aries to Pisces) that covered a full 360-degree circular path. At any time, they could look at the sky and see which constellation appeared to be closest to the Sun and infer what time of the year it was. If the Sun had just “entered” the constellation Aries after “exiting” Pisces, it had to be New Year’s day (April 14th). If it had just “entered” the constellation Capricorn, it had to be Sankranti (January 14th). Ancient Indian astronomers (as well as some other societies like the Greeks) were very adept at making such fine observations.

Logically, both the solar methods should give the same day count for a year. They nearly do, but not quite. The Gregorian calendar (also called the Tropical calendar) gives 365.2421 days; the Hindu calendar (also called the Sidereal calendar) gives 365.2563 days. That is, the Hindu year is about 20 minutes longer than the Gregorian year! It may sound trivial, but that makes a difference of one day every 72 years. Most of us who were born in the 20th or 21st century have never seen Sankranti on any day other than on 14th January. But if you were born before World War I you might have celebrated Sankranti on January 13th; and, if you were a contemporary of Pope Gregory, you would have completed your Sankranti prayers on January 9th!

So which calendar is the right one – the one with the extra 20 minutes or the one without? Well, there’s no right or wrong. Both theories make some assumptions and approximations. For example, the Hindu calendar assumes that the constellations are “fixed”. In reality, the stars in the constellations are moving at extremely high speeds. It’s just that because they are so far away, their movement makes little difference to our calculations.

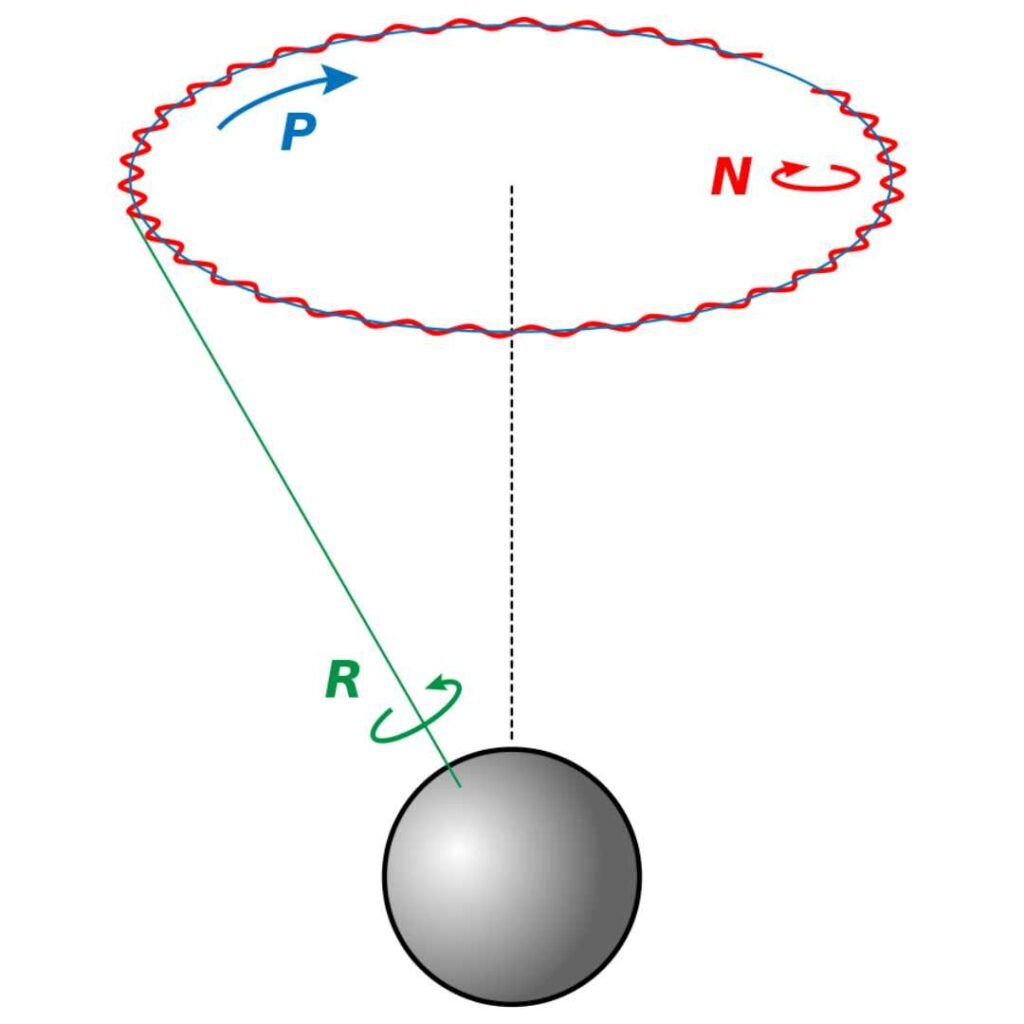

The Gregorian calendar, on the other hand, ignores a certain movement of the Earth completely. We all know that the Earth’s axis is tilted 23.5 degrees. Did you know that this axis too keeps moving? It tilts 23.5 degrees on one side, comes back to a perfect vertical, then goes 23.5 degrees to the opposite side, and then tilts back to 23.5 degrees on the original side. Think of the way a top wobbles when it spins; except, this wobble is very gentle and takes about 25,772 years to complete! Every year, this wobble (the scientific name for this wobble is “precession of the equinoxes”) adds 20 minutes to the Earth’s revolution time. And that is why the Hindu calendar year is 20 minutes longer.

But wait, why does the Earth wobble in the first place? The reason is its shape. The Earth is not a perfect sphere; it is an oblate spheroid – kind of like an orange. The gravitational pull of the Sun, Moon and neighbouring planets act differentially on the Earth and make it wobble. Isn’t it amazing that our ancients discovered its effect centuries ago?

Let’s circle back to Sankranti – why did our ancients choose the 14th of January to celebrate a spring festival? They did not. Because it is a spring festival, it most probably originated on the Winter Solstice. That day, 21st December, is significant in the Hindu calendar, because it heralds the arrival of spring. But remember, the Hindu calendar defines Makar Sankranti as “the entry of the Sun into the constellation of Makara (or Capricorn)” and not specifically as the Winter Solstice. So, every year these two days would have drifted apart by roughly 20 minutes – that’s why the Solstice is still on the 21st of December and Makar Sankranti, on the 14th of January. A back-of-the-envelope calculation says that around 143 BCE Sankranti and the Winter Solstice fell on the same day. That perhaps was the first ever Sankranti celebration!