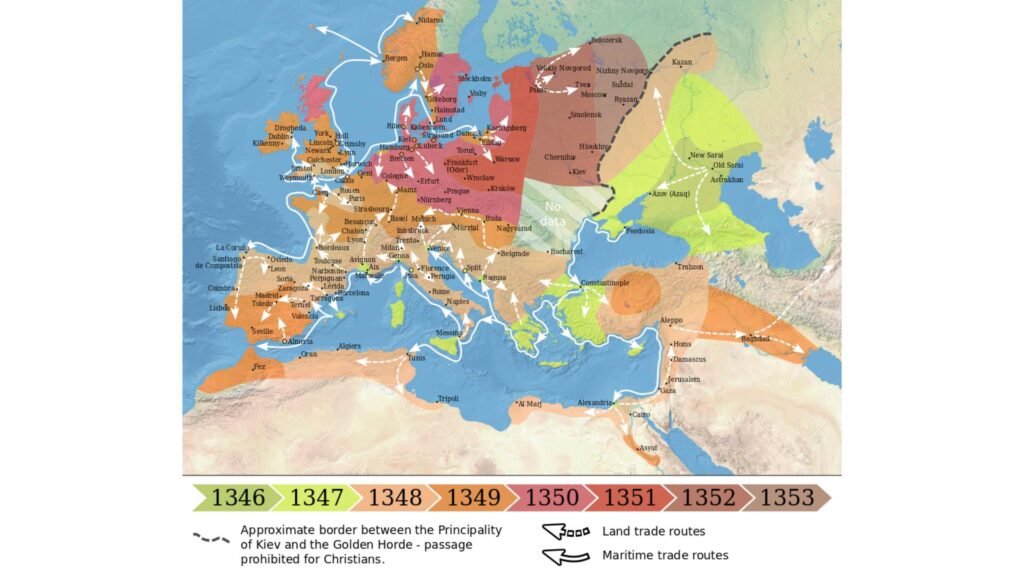

In the history of the world, there have been three truly terrible outbreaks of bubonic plague. The first began in 542 CE in Constantinople and killed 75 million people over two centuries. Then in the Middle Ages, it hit Europe and the Near-East as the infamous Black Death, killing a third of the population. Finally, in the 1850s, a third wave of plague that began in Yunnan, China, spread across Asia and the whole world.

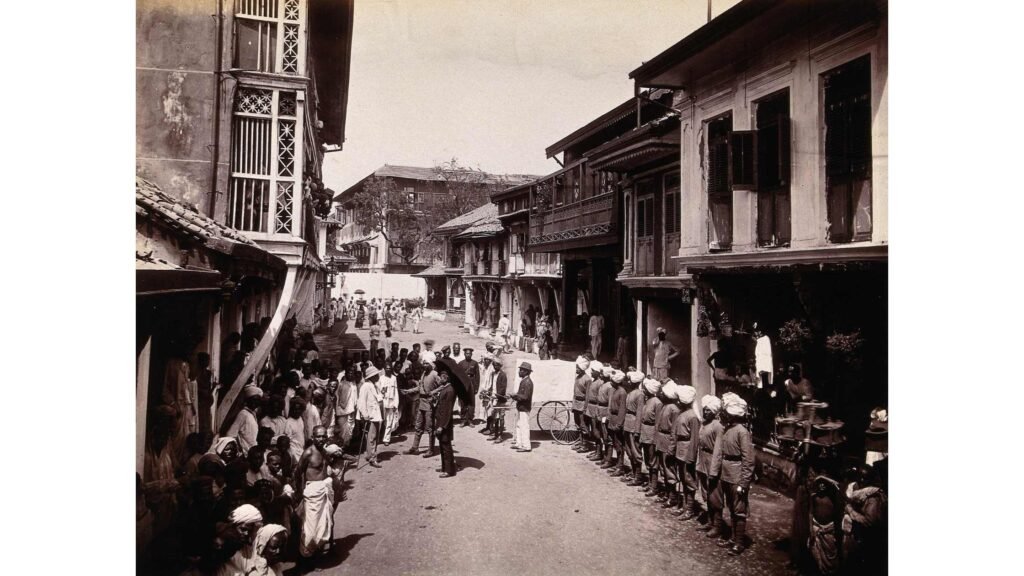

Bubonic plague struck Hong Kong in May 1894. Within a short time, this extremely deadly and virulent epidemic claimed a few hundred lives. When Hong Kong had its first deaths, the city administration rushed to contain it. Houses were checked, anyone with a runny nose was quarantined, and large parts of the city were disinfected regularly. Ideally, that should have been enough to contain the disease. But, Hong Kong was a busy port city with ships travelling out to other international ports every day. Many of those ships headed straight for Bombay (present-day Mumbai). Seaborne, the plague soon arrived in Bombay, a city which even in those days housed over 8,20,000 people. These ships were also carrying huge amounts of money, all made through the trade of opium – the stuff that Bombay was built on. When they got to the ports, the ships, with all the cargo and crew, were given a clear path into the city.

How did Bombay survive?

The first recorded case of the plague in Bombay was in the September of 1896, in the Mandvi port area (present-day Ballard estate). Acacio Viegas, the president of the Bombay Municipal Corporation and a medical doctor, was the one who discovered it. The plague soon spread from Mandvi. All along the port, houses were poorly constructed, drainage systems unhygienically planned, and garbage disposed of improperly. By the end of 1896, almost two thousand people were dying every week. And by the beginning of the new century, the plague had claimed 2.9 million people in the Bombay presidency alone.

In 1896 though, there was still hope that the disease could be contained. The local government jumped into action. Just like in Hong Kong, plague victims and possible victims were segregated, large parts of the city were shut down and movement into and out of the city was carefully watched. But none of this was done with a gentle hand. There are stories of suspected victims being dragged off trains, or being locked up or forced out of their houses. The result was a very distrustful general public. The various rumours doing the rounds did not help either.

One such rumour was that the plague wasn’t actually infectious, and that doctors were instead using it as an excuse to take people, kill them and extract a rare oil from their bodies! So people didn’t want to go anywhere near doctors and the police. In fact, when doctors tried to take a sick Hindu houseboy from the Parsi household he worked in, the Parsi women of the house – all 13 of them – gathered around the boy with knives drawn. They threatened to kill themselves if the doctors touched the boy.

If that wasn’t enough to deal with, thousands of people fled Bombay in those early years – nearly four hundred thousand people by one count. And many of them took the plague with them. Predictably, the disease spread.

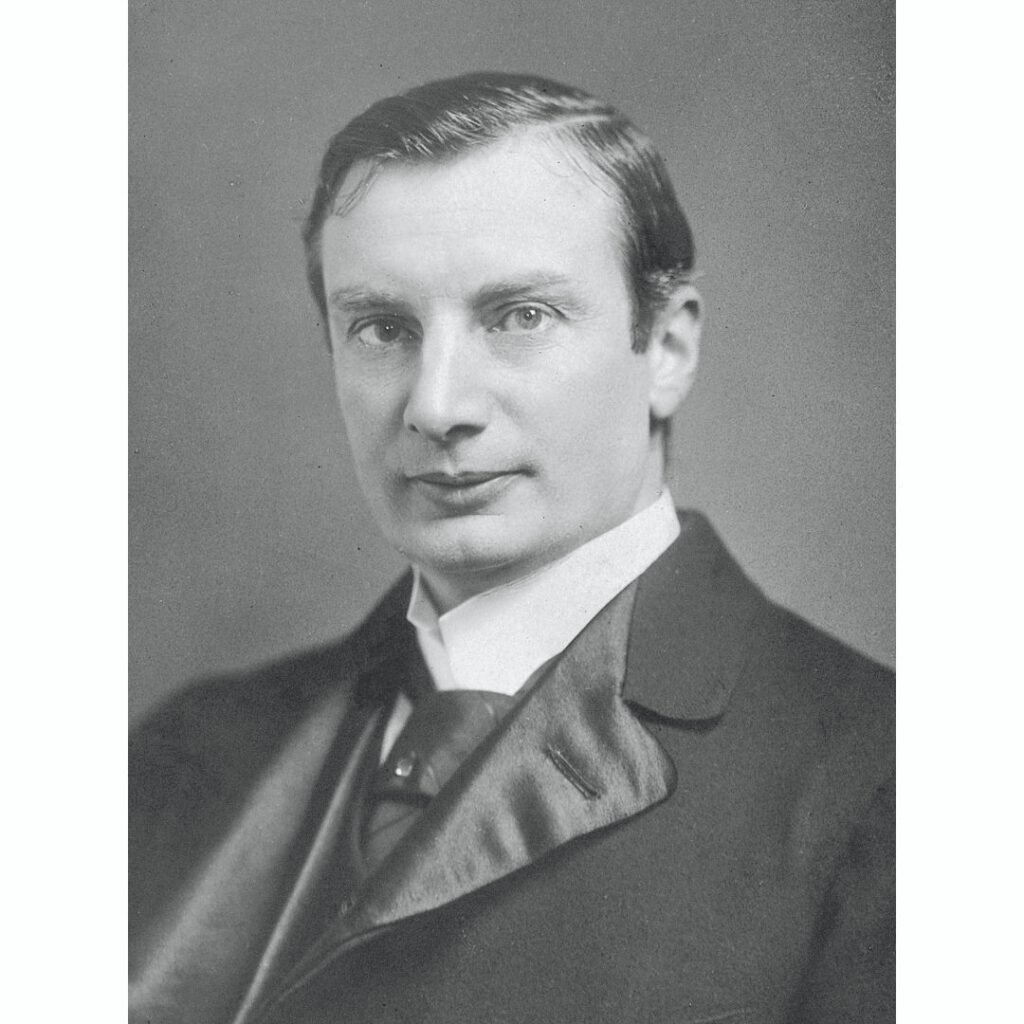

As doctors and researchers tried hard to understand the disease and find a cure, the Bombay government decided to invite a Dr. Haffkine from Calcutta (present-day Kolkata). Dr. Waldemar Mordechai Wolff Haffkine was a Ukrainian-Russian Jew who had migrated to France. He had studied under the famous Louis Pasteur and bloomed into a brilliant microbiologist (although the term was hardly known then). His work in discovering an anti-cholera vaccine received only a lukewarm response in Europe, so he had secured employment in Calcutta to pursue his mission. Within a short period he achieved dramatic success in containing cholera.

Dr. Haffkine arrived in Bombay in 1896, and immediately started work in a makeshift laboratory on Grant Road. Within three months he had a trial vaccine ready. Dr. Haffkine instilled confidence in others by vaccinating himself. Then it was tested in the Byculla jail. As expected, the vaccinated prisoners were protected while some unvaccinated prisoners contracted plague and died. The vaccine clearly worked, and mass vaccinations began. Bombay began to fight back.

The Bombay government allotted a former gubernatorial mansion to Dr. Haffkine in 1899, where he established the ‘Plague Research Institute’. In 1925, the grateful government renamed it as Haffkine Institute, and that is how this pioneering organisation is known now. Even today, the Haffkine Institute is one of the premier research organisations in India. However, that did not mean an end to the plague. For the next two decades, outbreaks continued across the country. By the end of the last outbreak in 1923, a hundred million people had lost their lives. But thanks to Dr Haffkine, the plague was finally defeated.