Have you ever wondered what it would be like to have your body taken over by spirits? There are several communities in India that engage in spirit possession rituals to this day. During these sacred rituals, spirits of local gods, deities and ancestors are believed to temporarily take possession of human bodies. These human bodies are then used as a medium for communication by the spirits to interact with the living world, often prophesying and acting as oracles.

The critically acclaimed Kannada-language film Kantara revolves around the Bhoota Kola tradition practised in certain parts of Karnataka and its role in shaping the communities in the region. Read on to discover 5 unique spiritual possession rituals across the country.

Bhoota Kola, Karnataka

In the Tulu Nadu region of Karnataka lies the coastal district of Dakshina Kannada. An age-old ritual called Bhoota Kola or Bhoota Aradhane has been widely celebrated by communities in the region. Bhoota’ means ‘spirit’, and ‘Kola’ means ‘play’ in the Tulu language. According to the Tulu paddanas (oral epics), the universe is divided into three realms – the gramya (developed lands, such as villages), the aranya (wild lands, such as the forests) and the realm of the bhootas (the spirits). The bhootas are said to act as mediators between the other two realms that are constantly at conflict. The ritual is carried out to pay homage to the bhootas, as disrespecting them will turn them angry and the balance between the realms will be lost.

The performers follow a strict regimen, which restricts them from consuming meat or alcohol and forbids them from engaging in sexual activities, as they prepare for their role. A bhoota is a semi-divine spirit that may be a heroic ancestor, a celestial being, a powerful animal or an element of nature. During the bhoota performance, which is called nema, the dancers dance to a frenzy to the heavy drum beats and music. The performers’ faces are fully painted, and they wear skirts made of tender palm leaves (which are easily flammable, intentionally worn to aid them in acts involving fire), heavy headgear and traditional jewellery. When they dance, they are believed to be temporarily possessed by bhootas, and act as oracles, providing guidance and foreseeing the future. There are several bhootas worshipped in the region; some include Panjurli (spirit of a male boar), Kallurti (spirit of a sculptor) and Pilichamudi (spirit of a tiger).

Kherai Puja, Assam

If the Bhoota Kola is about maintaining balance between realms, the Kherai Puja, practised by the Bodos of Assam, is about ensuring a good harvest. Agriculture is the chief source of this community’s sustenance and income. So once or twice a year, they come together for a grand celebration and offer prayers to Bathaou Brai, the Supreme God, and other minor gods and goddesses.

True to the spirit of the festival, it is a plant – the sacred sijou – that is considered to be a manifestation of the Supreme God. It is right at the centre of the ceremonies and is therefore offered fruits, flowers and grains.

During the days of worship, the Douri (male priest) and Doudini (female priest) play a key role, under the guidance of the Oja (incantist). Upon the Oja’s chants, the Doudini falls under a trance and is believed to be possessed by a divine spirit, leading her to temporarily become one of deities. Moving to the rhythm of the drums, flute and cymbals, the Doudini performs up to eighteen dances in front of the sijou and recites stories of the past and present and is believed to possess the power to predict the future.

Bonalu, Andhra Pradesh

In the year 1813, there was a plague outbreak in the twin cities of Hyderabad and Secunderabad. A military battalion deployed from Hyderabad is said to have visited the temple of the goddess Mahakali in Ujjain, where they prayed for the eradication of the disease, promising to install the goddess’s idol in Secunderabad in return. Devotees believe that the goddess was the reason for the end of the epidemic. And thus, it is said, began the yearly festival of Bonalu in the regions of Andhra Pradesh and Telengana.

During the festival, it is a tradition to offer bonam, which literally translates to ‘meal’ in Telugu, to the Ujjaini Mahakali idol, as women carry earthenware pots filled with cooked rice, water and jaggery on their heads and head towards the temple where the idol sits. It is believed that these women are possessed by the spirit of the goddess, and to pacify the spirit, devotees sprinkle water at their feet.

Nagamandala, Karnataka

Other than the Bhoota Kola, the Tuluva community of Tulu Nadu also have the Nagaradhane, a custom of worshipping the serpent god. The snake god is considered to be a symbol of fertility with special powers. The tradition consists of two distinct rituals, including the Nagamandala and the Aashleshabali.

During the Nagamandala, a procession of dancers and musicians playing the dakke (a cylindrical percussion instrument) and pipe instrument moves out from the nearest nagabana (serpent grove) into the pandal. The ritual is performed by two priests, Patri and Nagakannika, who represent the male and the female snakes, respectively. Patri, dressed in a red dhoti, inhales the scent of the areca flowers and enters a trance, wherein it is believed that their body is taken over by the spirit of the male snake. Nagakannika is dressed in a curious and striking costume and dances around the mandala along with Patri, signifying the sacred union between the male and female snakes. The tradition pays homage to the serpent god who is believed to protect the community from evil.

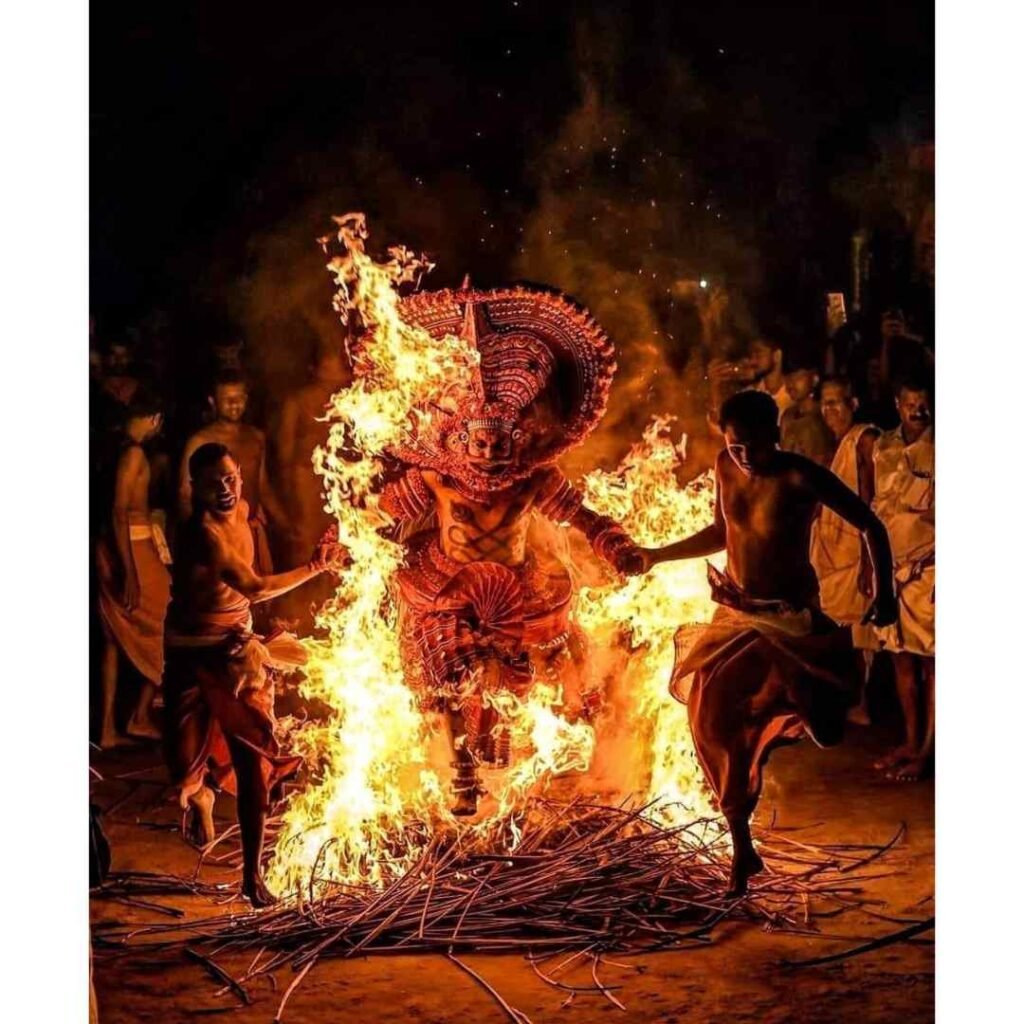

Theyyam, Kerala

In the state of Kerala, popularly referred to as ‘God’s own country’, it is but natural for the gods to take centre stage. During Theyyam, local deities are worshipped in a grand festival that takes place in the months of October-May. That’s right! Celebrations last for about seven entire months.

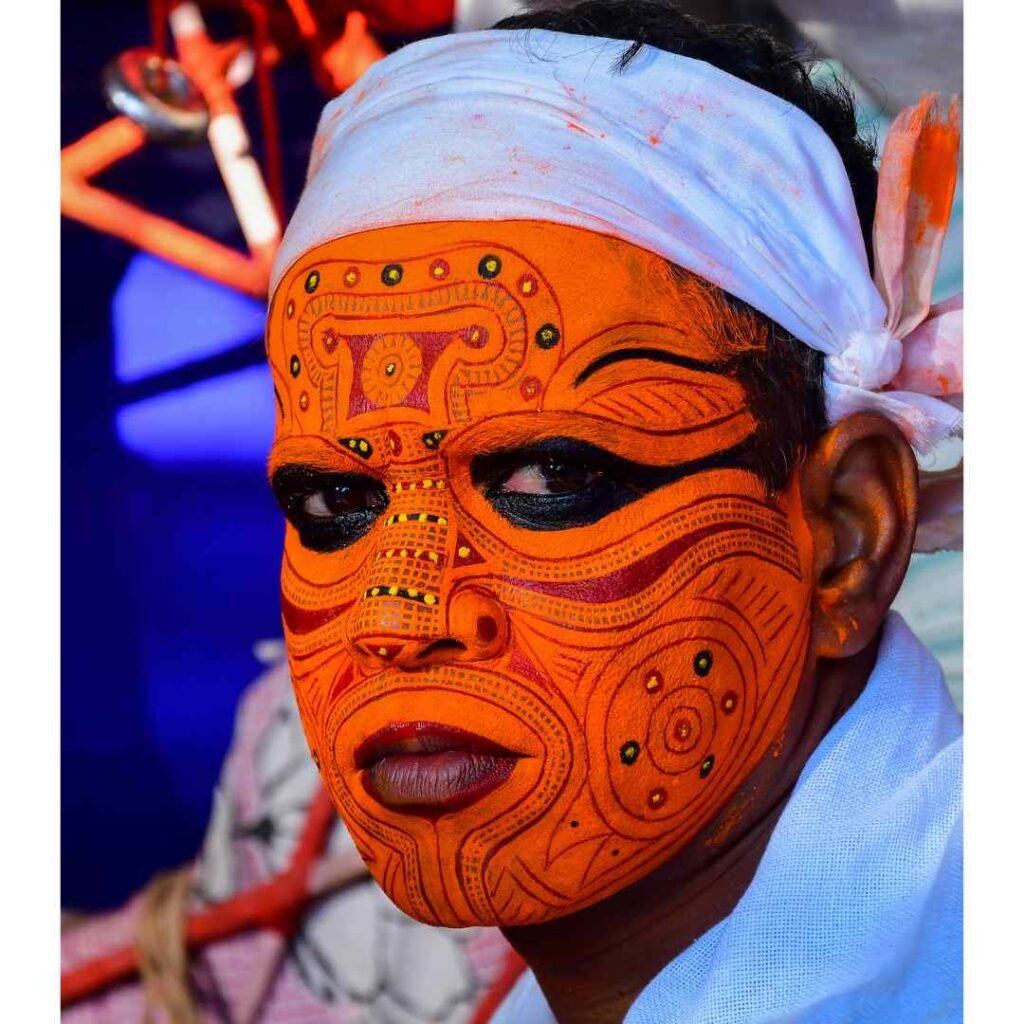

Theyyam is believed to have its origins in ancient tribal rituals. Theyyattam (meaning ‘god-dance’)is enthusiastically performed by male artistes, who usually always come from families that have traditionally performed the dance. The faces of the performers are painted with fantastic designs, and they wear flamboyant costumes that include heavy ornamentation and headgear. It can sometimes take up to 10 hours for a performer to get ready! The performance includes dance, music and mime, as devotees pay their respects to spirits and deities and their own ancestors. Theyyam begins with the thottam, a ballad sung as an invocation, during which myths and legends associated with the deities are recited. Accompanied by traditional instruments, such as chenda (a percussion instrument made of wood, leather and parchment) and elathalam (miniature cymbals), the performer is believed to be slowly possessed by the spirit of the theyyam.

There are over 400 distinct theyyams, each with its own unique set of facial features, makeup, costumes and traditions, each majestic in its own right. Some of the theyyam deitiesinclude Raktha Chamundi (an incarnation of Goddess Kali) and Bali (a mythical character from the Ramayana), amongst several others. During the performance, the performers enter a trance-like stage, feeling united with the deities, and devotees believe that during that moment the humans are possessed by the spirits themselves, and so they take their blessings.