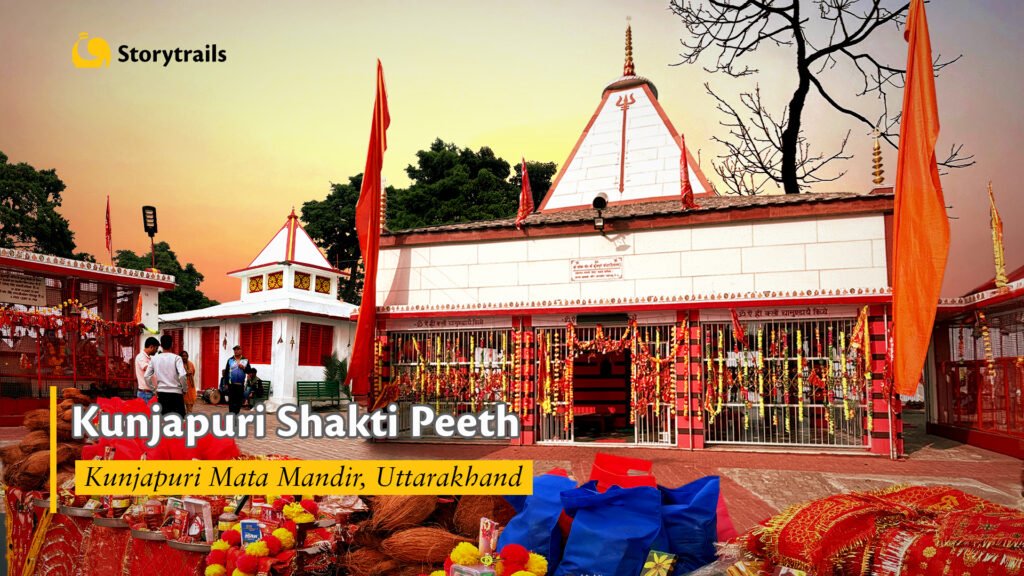

The lotus is India’s national flower. Hindu Gods are often shown seated or standing on a blooming lotus or holding one. In Hinduism, the flower represents beauty and purity. The supreme Hindu god of creation, Brahma, is said to have emerged from inside a lotus. But Hinduism isn’t the only religion to consider the lotus as a sacred symbol.

Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism – all the three ancient religions originating in India have adopted the lotus as their own. The flower holds religious and mystical significance wherever it grows throughout Asia, especially in India, China and Vietnam. And Buddhist architecture in these countries is replete with lotus iconography. In fact, early Buddhist sculptures never represented Buddha in his natural physical form, but often as a lotus. The symbolic interpretation was that though Buddha was born on earth, he floated above earthly attachments, just like the lotus flower does above water.

The domes of ancient Buddhist stupas in India are often lined with circular designs denoting a lotus.

Detour: Why was Buddha represented by symbols like the lotus, wheel and a begging bowl? Watch this short video to know more.

But the lotus’s mystical roots have a more global reach. For ancient Egyptians the flower was revered as a representation of Ra, the sun god. The flower, like Ra, closed up for the day every evening, ostensibly sank in the water and rose and bloomed again every morning. It was thus a symbol of rebirth. It would soon become more.

Before the emergence of Egypt as one of the great ancient civilisations in the world in 3000 BCE, Ancient Egypt was actually divided into two: Lower Egypt to the north occupying the Nile Delta and Upper Egypt to the south, occupying the land on either side of the first half of the Nile. The first Egyptian pharaoh, Menes, is said to have united these two lands under him. Once the two lands were united, the blue lotus that grew in Upper Egypt and papyrus that grew in Lower Egypt joined to become a symbol of the united Egypt. Hieroglyphics and art from that time period and after often include icons showing the two water plants intertwined or being tied together by an Egyptian god and the pharaoh.

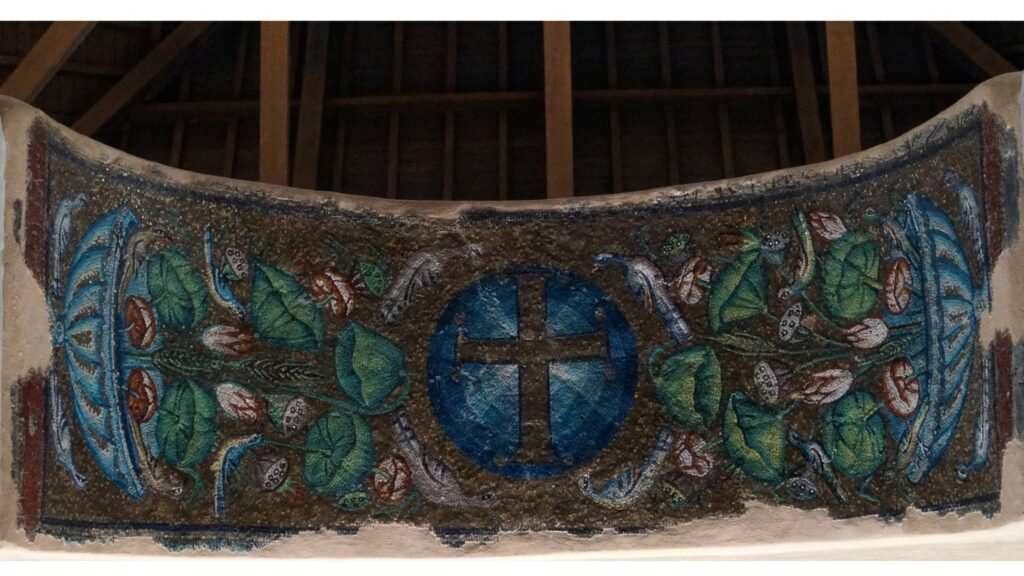

The lotus as a symbol also crept into Christianity somewhere around the 5th century. This is when a council of Christian Bishops convened in Ephesus in present-day Turkey to formally declare the virgin Mary as Theotokos, the mother of God rather than merely the mother of Christ. The result was a proliferation of church buildings dedicated to the Virgin Mother replete with depictions of the white lotus plant.

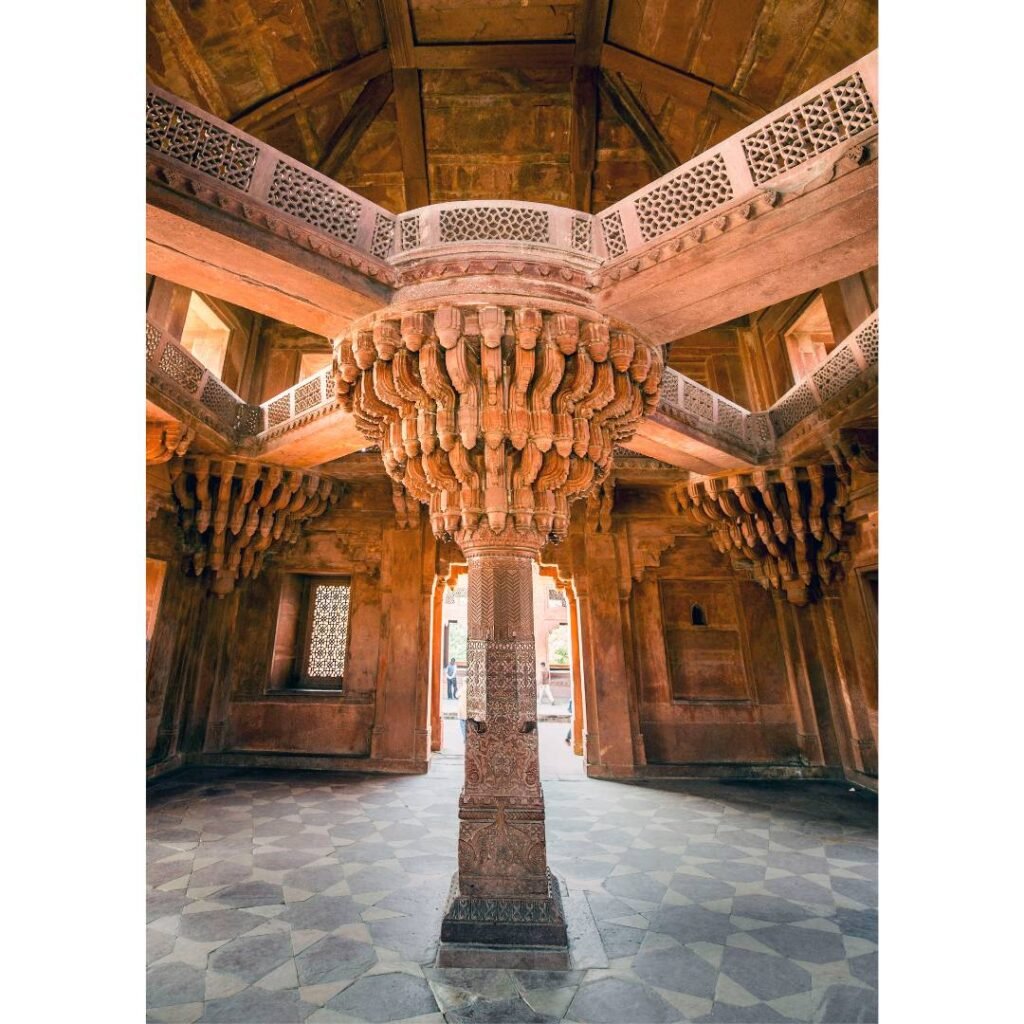

Much later in the 13th century, the Mongols invaded Western Asia. The lotus as an icon was already a favourite in China and soon, it started appearing in Persian Islamic art. Then in the 16th century, a Persian prince decided to take over India. The result was the Mughal empire. The lotus became even more important in Mughal art, strengthened now by Indian, Chinese and Persian takes on the flower’s representation.

One of the best examples of this can be found in Fatehpur Sikri in Uttar Pradesh which served as the Mughal capital for 14 years. Here, the throne pillar in the Diwan-i-Khas or the Hall of Private Audience shows influences of all major Indian religions and even Christianity. Akbar, who ruled from here for a while, was known to hold syncretic views on religion. The most easily identifiable symbol when you look at the pillar as a whole is the lotus. Even the dome of the beautiful Taj Mahal in Agra commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in 1632 is decorated with an inverted lotus design.

The lotus flower may be an ancient symbol, but it has continued to influence religious art and architecture till quite recently. The Lotus Temple in Delhi was formally inaugurated in 1986. The temple belongs to the Bahai Faith, a modern religion that emerged in the 19th century. Isn’t it fascinating that even this religion chose to adopt this symbol?

Look for more on the lotus as a Buddhist icon in the Amaravati gallery of the Government Museum, Egmore, Chennai. Download the Storytrails app (www.storytrails.app) and explore stories of this gallery – the oldest Buddhist art collection in the world, in the ‘Best of Egmore Museum’ audio tour.