In 2015, on the banks of the river Vaigai, near Madurai in Tamil Nadu, archeologists unearthed, among several other artefacts, a potsherd with the name ‘Kuviran’ scratched on it in Tamil Brahmi script. And that offered many clues to the archaeologists about that civilisation: it told them about the language and literacy levels, the social hierarchy and the age of a civilisation. What is now known as the ‘Keeladi excavations’ point to the existence of a literate society in parts of South India nearly 2,500 years ago! But how can broken pottery fragments give archaeologists such great insights into our past?

Pottery was invented around the same time that mankind opted for a sedentary lifestyle. Around 6500 years ago, man settled around fertile river valleys and started cultivating the land. However, he had still not invented irrigation. So, to water his crops, he needed some way to carry water from the river to his field. The closest available material was the clay around the river beds. It was malleable, inexpensive and abundant. Even better, it could be easily moulded to any desired shape. A roughly shaped and baked container was probably the first clay vessel to be born.

Cut to many thousand years in the future. The potter now had the pottery wheel. This was a huge step in the evolution of pottery. The potter could now turn the pot as he worked on the clay. This led to a more symmetrical and uniform design. The potter was also creating scratches or patterns on the clay before they were baked. This was how the earliest pottery decorations came to be.

Over time, pottery has evolved to more complicated techniques and materials. But these old ware have stood the test of time and we still find fragments of early pottery at various archaeological dig sites. Why, unlike any normal, natural material, have these ware not degraded? Thanks to a unique property, clay, once baked, becomes completely impervious to decay. It might break and fragment, but it will not degrade. This is a blessing for all archaeologists who use these fragments to understand the lives and times of our ancestors. By using techniques like carbon dating, experts can pinpoint the age of the artefacts with reasonable accuracy.

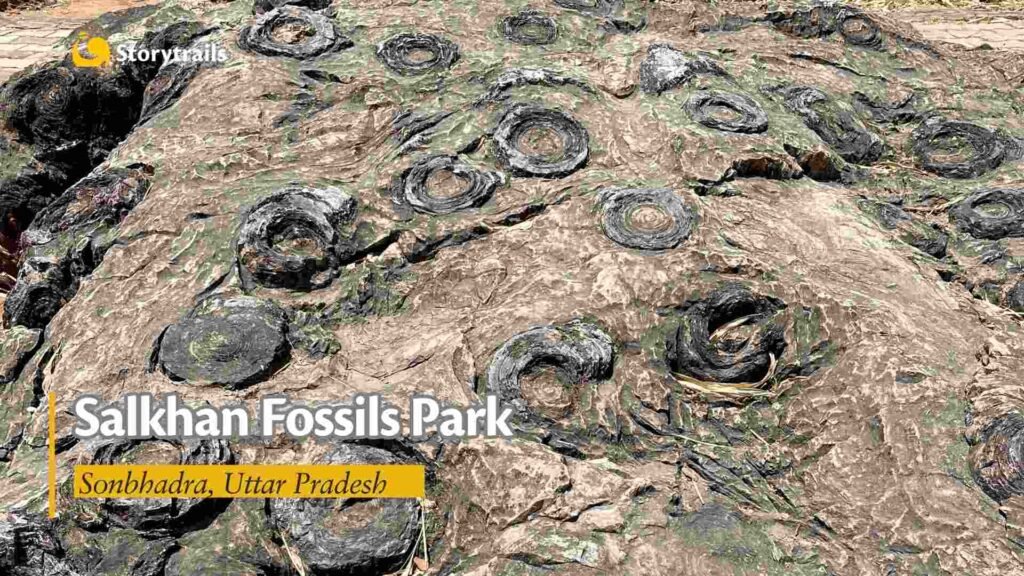

In the Indian subcontinent, the earliest known pottery was discovered in Lahuradewa ( in the Gangetic Plain of Uttar Pradesh) and is dated to 7000 BCE.

The most well known, of course, is the Indus Valley Civilization. The Indus Valley Civilization was spread over parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India and lasted from around 2500 BCE to 1700 BCE. And it is interesting to observe how the archaeologists are able to put together a composite picture by observing the artefacts.

The Dancing Girl is a symbol of Mohenjo Daro. And here is another picture of a potsherd from Bhirrana, Haryana, India. Observe the resemblance between the figures. Did two artists from these two different locations come up with the same design independently or did one inspire the other? It is like putting together an intricate jigsaw puzzle, except that some pieces are currently out of sight.

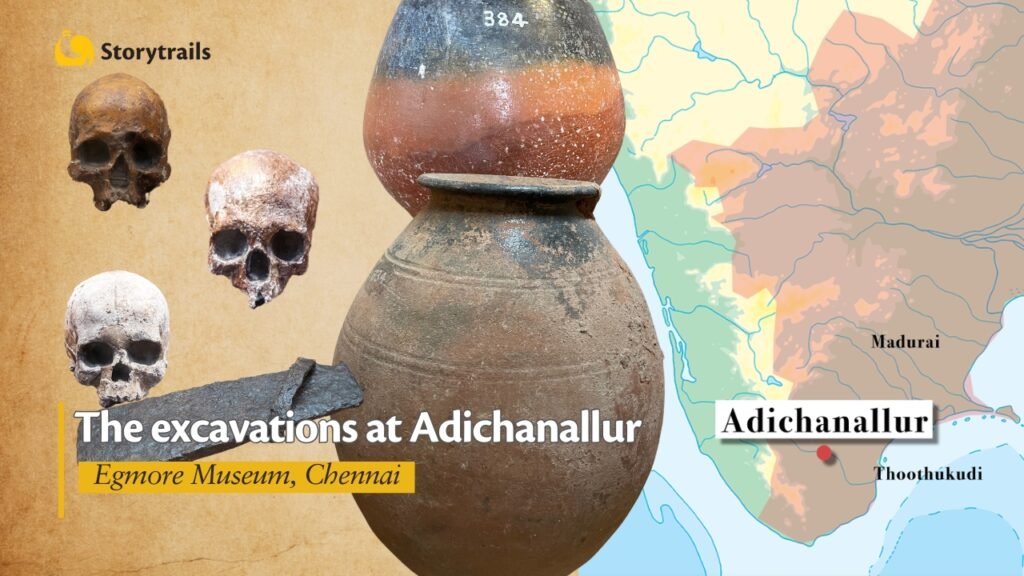

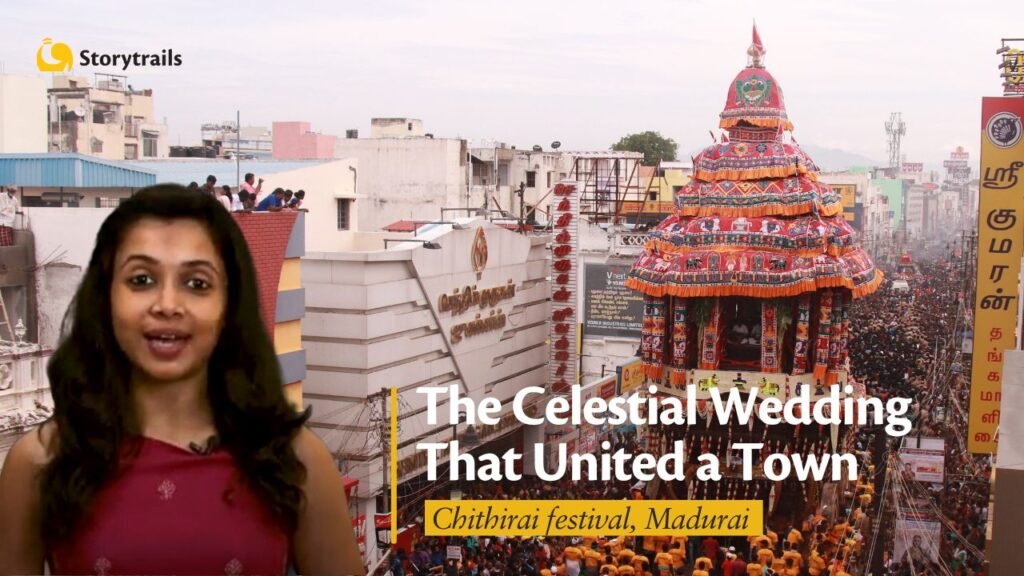

Down south, the recent excavations at Keeladi, a small village near Madurai, Tamil Nadu, yielded many artefacts. Since 2015, archaeologists have dug up nearly 300 sites all along the Vaigai river – an area that is now called the Vaigai River Valley Civilisation.

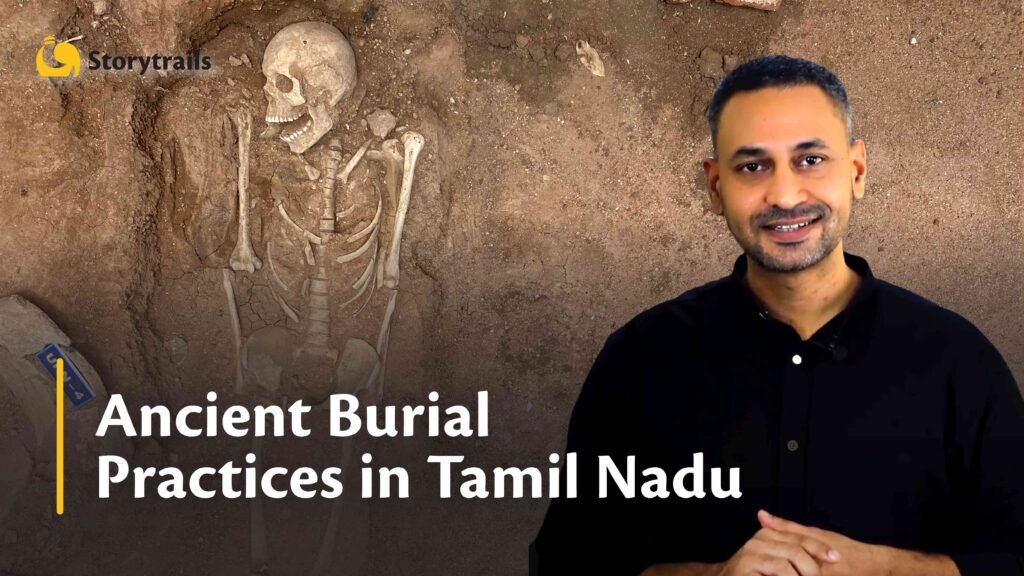

One of the most exciting discoveries in Keeladi was the unearthing of potsherds with etchings, suggesting that there was an urban and literate society in Tamil Nadu nearly 2600 years ago. In fact, these discoveries have pushed the edge of known history of south India back by three centuries, from 3rd century BCE to 6th century BCE!

Some of these fragments bore names like ‘Kuviran’ and ‘Aathan’. Archaeologists believe that these were not just names of the residents of Keeladi, but some of them were honorifics or titles, suggesting the existence of a hierarchy in the society.

The finds are not just restricted to potsherds. Excavations have yielded terracotta sculptures, gold jewellery, beads etc suggesting that the society was well to do and could afford these luxuries. They also found terracotta roof tiles and water pipes, suggesting that the people of Keeladi were knowledgeable in water management too.

Another interesting fact is that these potsherds were discovered at various layers of the site. Those discovered in the upper layers have inscriptions in the Damili script, an early precursor of modern Tamil. A little deeper, the potsherds of the middle layers had inscriptions in both Damili and some other scratch marks. Epigraphists call these ‘graffiti’. And potsherds found deeper still bore only these graffiti marks. Some of these graffiti marks are remarkably similar to the Indus Valley script that remains undeciphered to this day. The Indus Valley Civilization existed around 2500 BCE, and we now know that the Vaigai valley civilization was at least as old as 580 BCE. Could this mean that the Vaigai Valley Civilisation was older than we know now? Or did the people of Keeladi have ties with the people at Harappa or Mohenjo Daro? Or did the Harappans migrate south?

The excavations are still ongoing and it is likely that they will bring us more answers and many more questions – all adding to our understanding of our past!